Neighborhood Church congregation on the steps of the church sanctuary. (Photo obtained with permission from Neighborhood Church.)

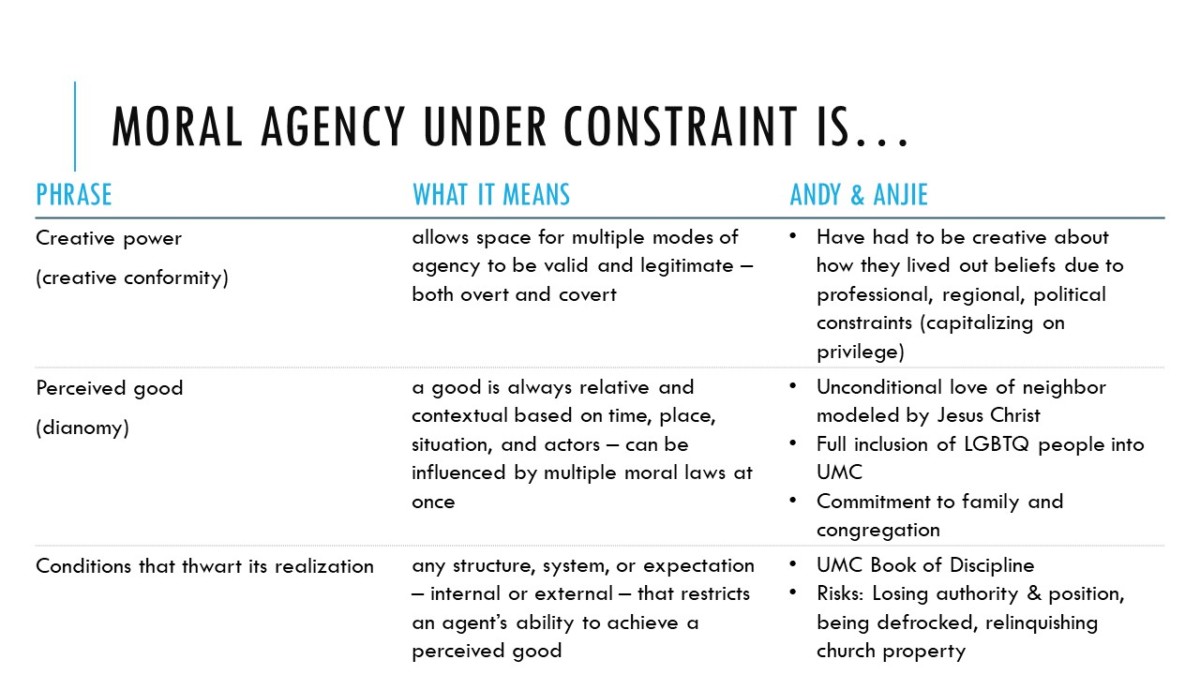

What Counts as Activism?: A Case Study in Moral Agency Under Constraint

In 2019, the United Methodist Church found itself in the national spotlight at the center of ongoing debates about the full inclusion of LGBTQ people at all levels of society. 1 Conservative and progressive factions of the church are deeply divided over the inclusion of LGBTQ members, and plans for a church split are underway. UMC clergy who support full LGBTQ inclusion into the church are currently in the position of having to live out progressive values within the confines of the UMC’s exclusionary doctrinal positions. These clergy, I argue, are prime examples of moral agents under constraint. For this project, I will highlight two UMC clergy – Reverends Andy and Anjie Woodworth, married pastors of Neighborhood Church in the Candler Park neighborhood of Atlanta, GA – and discuss the various means by which they have advocated for LGBTQ inclusion over the course of their ministry, and how that advocacy has changed over time.

Employing Elizabeth Bucar’s theoretical framework of dianomy, I will argue that the Woodworth’s are dianomous moral agents because their actions as UMC clergy are not only determined by the United Methodist Book of Discipline, but also by their ideological leanings based on the teachings of Jesus Christ, and their responsibility to their family and congregation. Bucar’s related idea of ‘creative conformity’ will serve as an interpretative tool to understand the Woodworth’s modes of operating within the constraints of the church.2

By embracing a theory that rejects a black-and-white understanding of agency in favor of shades of grey, this project seeks to complicate all-or-nothing notions around activism that fail to consider people’s everyday circumstances and discredit more subtle approaches. This move toward inclusiveness is significant, because when we limit what counts as “real” activism to include only direct confrontation, we create an exclusionary environment in which potential activists will self-select out of movements because their circumstances do not allow for overt modes of resistance. Enacting long-term systemic change is all-hands-on-deck work, and it is just as important to honor those who work inside systems with complicated legacies to effect change from within as it is to valorize more visible, outspoken actors.

Reverends Andy & Anjie Woodworth of Neighborhood Church

Reverends Andy and Anjie Woodworth are Atlanta natives and life-long United Methodists. They both accepted their calls to ministry at an early age and met in their early twenties while serving as youth ministers at UMC congregations in the Atlanta area. The Woodworth’s married shortly before enrolling in the Master of Divinity program at Candler School of Theology at Emory University, an institution with deep ties to the UMC.

Andy and Anjie have co-pastored Neighborhood Church since the summer of 2016. Neighborhood Church is located in Candler Park, an affluent and politically progressive neighborhood in the heart of Atlanta. It is the result of a merger between Druid Hills UMC and Epworth UMC, two smaller congregations that united in order to remain viable and active.

This post unfolds in four parts:

- An introduction of the theories that frame my understanding of the Woodworths’ work.

- An overview of the context of the debate around LGBTQ inclusion in the United Methodist Church.

- A journey through the four stages of the Woodworths’ ministry and the various constraints and acts of agency experienced at each stage.

- A discussion of why highlighting moral agents like the Woodworth’s holds importance for the future of activism.

Theoretical Framing

The lens through which I view the Woodworth’s moral agency is informed by Elizabeth Bucar’s conceptions of creative conformity and dianomy.

Dianomy, which means ‘dual sources of the moral law,’ “[accounts for moral agency that relies neither exclusively on the self as a source of moral authority nor exclusively upon religious traditions.”3 A dianomous view of agency understands that agents are “formed by several discourses at the same time,” which is the nature of the human condition.4

Creative conformity is essentially a model of of dianomous agency. Bucar describes creative conformity as “simultaneous processes of complicity as well as resistance.” Creative conformity considers the validity of moral actions by agents who “see themselves as existing within the structure of other representations, and as operating inside those lines.”5

Dianomy and creative conformity account for the fact that morality is not fixed or absolute. It is instead ambiguous, partial, and imperfect. Indeed, because “there is no autonomous place of perfect freedom”6, there exist only imperfect attempts at morality.

Viewed through this lens, the Woodworths can be considered dianomous agents in that their actions are determined by and subject to many moral laws, including the UMC Book of Discipline and what they perceive to be the core message of the Gospel of Jesus Christ: unconditional love. As Anjie states, “I think I would define my morals as centered in Christian teaching or in Christ, and for me, that’s embodying God’s love. So, I would say its core is living out God’s love in all things. And that gets much more complicated that it sounds. It involves more resistance and culture-subversion than it sounds like it would, but to me that’s really what it is.”7

What this statement neglects to acknowledge is that for the Woodworth’s, “living out God’s love in all things” has also meant adopting a stance of creative conformity, particularly at the beginning of their journey as young pastors of conservative churches. These instances of creative conformity, however, because of the ways in which they have preserved the Woodworth’s position as clergy and thus elevated their platform for advocacy, have proven to be critical sources of moral agency. Indeed, the creative conformity employed at the outset of their ministry laid the foundation for the Woodworth’s to advocate for LGBTQ inclusion in a more overtly resistant mode.

The notions of creative conformity and dianomy align nicely with Ellen Ott Marshall’s definition of moral agency under constraint:

Claiming the creative power to act according to a perceived good under conditions that thwart its realization.8

Creative power is critical to any definition of moral agency because it is not dogmatic, because it allows space for a plurality of methods to approach a given situation to all be valid and legitimate. Each of us is imbued with our own creative power, generated by our unique perspectives. Thus, all approaches to moral agency will look different. The emphasis on a perceived good is critical to this definition because it reflects an understanding that a good is always relative and contextual, based on time, place, situation, and actors. Finally, the concept of constraint as any condition that thwarts an agent’s realization of a perceived good is sufficiently broad to account for a variety of circumstances. A constraint, therefore, could be any structure, system, or expectation that requires an agent to employ creative power to achieve a perceived good while also weighing the risks associated with doing so. While this definition arguably bears the implicit assumption that agency is always resistant, I contend that this definition rejects the tendency toward the romanticizing of resistance because its activation of creativity toward a perceived good allows for a fluid understanding of agency that aligns with dianomy and creative conformity.

The United Methodist Church and Debates Around LGBTQ Inclusion

With 12 million members, the UMC is the second largest Protestant denomination in the United States and has grown to span the globe, with special missionary focus in Africa and Asia.9 The UMC has no single leader and is instead governed by a Council of Bishops who set policy and make recommendations for regional bodies. The UMC is comprised of multiple locally-based administrative bodies, called “annual conferences,” which meet once a year to discuss the concerns of a given region. Every four years, a General Conference is convened, which is an international group of 1,000 delegates that represent all annual conferences across the globe. Only this body can make amendments to the United Methodist Book of Discipline (BoD) and set official policy that affects the entire denomination.

The BoD contains the church’s foundational documents and doctrinal positions. The BoD did not originally contain language or rules around homosexuality, but as the culture wars raged toward the end of the 20th century, explicitly exclusionary language was gradually added to institutionalize the exclusion of LGBTQ people in the Church. Any clergy person who flouted these rules was at risk of being sanctioned by the church and having their ordination revoked. While Americans created the rules, they have been maintained and supported at General Conferences by votes from delegates from the Global South, who tend to lean more conservative than the UMC population in the United States.

The practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching. (1972)

Self-avowed practicing homosexuals are not to be certified as candidates, ordained as ministers, or appointed to serve in the United Methodist Church. (1984)

Ceremonies that celebrate homosexual unions shall not be conducted by our ministers and shall not be conducted in our churches. (1996)10

The language around homosexuality in the BoD has been a source of heated debate since it was originally included. There has been advocacy on both ends of the ideological spectrum, which has damaged the cohesion of the UMC. This has resulted in inconsistent application of the results and disciplinary action. Annual conferences in the Northeast and the Pacific Northwest, for example, are much more permissive around LGBTQ inclusion than those in the Southeast. In fact, to join the Massachusetts Annual Conference, clergy have to vow not to uphold the LGBTQ-related disciplinary language. However, in other parts of the country, UMC clergy have been called up on charges related to not complying with the discipline and have had their clergy status revoked.

Ideological and practice differences around LGBTQ inclusion so impacted the functioning of the UMC that a plan for a schism was brought to the 2016 General Conference (GC 2016). While the plan was ultimately voted down, it brought to the forefront the need for denomination-wide action around the LGBTQ issue. Shortly after GC 2016, the Council of Bishops assembled a group called The Commission on a Way Forward (COWF), a cohort of 32 United Methodist clergy and laypeople, with the goal of “[exploring] options that help to maintain and strengthen the unity of the church.” The COWF held that the UMC should be united on common ground by Christian and Methodist principles and that homosexuality should not be a church-defining or a church-dividing issue. At the UMC General Conference special session in February of 2019 (GC 2019), which was convened to decide on the question of how to address the future cohesion of the church in light of this debate, the COWF put forward two options for the future structure and administration of the UMC for the delegates to vote on. What was at stake was the question of LGBTQ inclusion in terms of the ability for openly LGBTQ clergy and the clergy’s ability to celebrate same-sex unions, and whether disagreement about this subject would result in a church split.

The One Church Plan, supported by the Council of Bishops and the UMC’s more progressive-leaning members and congregations, would have left decisions to allow same-sex marriages to individual congregations and LGBTQ ordination to annual conferences. The other plan put forward for consideration was the Multi-Branch Model, which would have split the UMC into three separate branches – Centrist, Traditional, and Progressive. The branches would have operated in blocs along ideological lines while remaining United Methodist.

Ultimately, the Traditional Plan was adopted for the entire UMC, meaning that all exclusionary language would remain in the BoD and that legal action would continue to be taken against clergy who flouted the doctrine. This outcome was seen as an overwhelming victory for the conservative faction of the church and an abject failure for progressives.11

Activism Throughout the Woodworths’ Ministry Journey

It is against this backdrop of the contentious, ongoing debates around LGBTQ inclusion in the UMC that we will examine the Woodworth’s ministry journeys and the ways in which the pastors have employed creative conformity to act as moral agents under constraint. Across the lifespan of their ministry, the Woodworth’s have encountered various constraints – from the BoD to the wishes of their congregation – that have limited their agency with regard to full LGBTQ inclusion. However, at each step along their path, the Woodworth’s have creatively resisted these constraints, maneuvering within the system to work toward the changes they seek.

Stage 1: Ordination

During the ordination process, UMC clergy candidates are required to vow to uphold the BoD. However, the ordination process for both Woodworth’s was unique in that they never hid their disagreement with the LGBTQ-exclusionary language in the BoD from evaluators. Anjie made it clear that she disagreed with the UMC stance of restricting LGBT inclusion and that she would be actively working to change it. But, she says, “No one cared. They already had me flagged as a liberal and they just didn’t care… I never got any pushback.”

When Andy was being interviewed for ordination, a conservative member of his interview panel asked how Andy would uphold the part of the discipline that restricted LGBT inclusion. Another one of the interviewers interrupted the question, saying, “Andy’s from St. Paul [a historically progressive UMC congregation], so we all just know how that goes. Let’s move on.” Thus, Andy and Anjie were both ordained in spite of the fact that UMC officials were aware of their disagreement with the language around LGBTQ issues in the BoD.

While it is commendable that their resistance to the denomination’s exclusionary language and practices was present from the outset of their careers, it could be argued that, had the Woodworth’s truly intended to be fully inclusive clergy, that they would have sought affiliation with another, more inclusive denomination. Yet, these young clergy remained committed to the UMC to honor other ties that bound them to their denomination of birth. The choice to align with the UMC made the Woodworth’s immediately complicit in reifying the church’s exclusionary doctrines because in order to succeed as clergy, they would have to operate within the church’s constraints against their better judgement. “Operating within” and “pushing against” have always been simultaneous processes for the Woodworths, though, and while simply naming their resistance at the outset of their careers might not have changed the system immediately, it did plant the seed for the other modes of resistance the Woodworths would employ later on.

Stage 2: Early Ministry

As young pastors, the Woodworths led predominantly white, affluent, conservative churches. To maintain functioning congregations and develop pastoral relationships within those congregations meant that their advocacy had to consist primarily of having “quiet conversations.” These quiet conversations were a form of creative conformity in that, while the Woodworths were not explicitly challenging church doctrine, they were quietly confronting the underlying conservatism that informed the ideological stances in the BoD. They prioritized forming relationships over outright resistance because they viewed relationships as fruitful avenues toward creating more social-justice-minded congregations in spaces where difficult conversations were rarely had.

Early in her ministry, Anjie was called to work at a church in west Georgia, and she “would always want to push people in conversations, you know…. I still talked to people slowly and carefully, but we definitely felt like liberals on the down-low. Like [we] had to hide who we were…We had conversations, but it was very subtle, very careful, very quiet.” Similarly, Andy veiled his political stances in his sermons: “I don’t think I ever said anything as explicit as, ‘Hey everybody, did you know that LGBTQ people are made by God and loved by God and we should love them, too?’” Andy’s statement makes it clear that their moral agency is informed not just by doctrine in the BoD, but by a progressive theological interpretation of the Bible and the message of Jesus Christ.

Andy is really gifted at preaching Jesus. And if you preach what Jesus teaches in the gospel, it is what our country defines as radically liberal. I mean, socialist, even. And so, he was really great at helping those folks think through social justice issues… Andy didn’t use the word social justice always, but talked about social holiness in the Wesleyan tradition…[He’s] really gifted at flying in under the radar and preaching the Gospel and helping people transform their thinking, and then all of a sudden, they’re like, ‘Wait, I think I might be progressive.’ (Anjie)

Using veiled approaches to activism helped Andy and Anjie to accomplish “radical things” with congregations that never would have described themselves as liberal, but who were “living Gospel truth.” They back their decision to not be more public about their stances by positioning it as a necessary political move that maintained the integrity of their authority within the church and their ability to impact change: “If I had publicly aligned with RMN [Reconciling Ministries Network], it would have been over” (Andy). What this teaches us is that context matters tremendously when it comes to how moral agency is enacted, and that oftentimes gradual, partial, imperfect methods are able to accomplish more work toward a perceived good than more extreme forms of resistance.

Stage 3: Neighborhood Church Phase 1 (Pre-GC 2019)

The Woodworth’s advocacy around LGBTQ inclusion took a more explicitly activist turn when they became the pastors of Neighborhood Church (NC) in 2016. Because NC, as a combination of Epworth and Druid Hills UMCs, was essentially a new church plant, Andy and Anjie could lead the development of the vision and culture of the church from the very beginning. Being there at the inception of the congregation has given the Woodworth’s increased freedom to preach and minister exactly as they feel God has called them to do. Further, their freedom to be more explicitly resistant is supported by the fact that the two congregations leaned progressive before they arrived and that NC is located in Candler Park. Those pre-existing conditions gave them the ability to “[come] in with the straight-up assumption this would be a progressive congregation” (Andy). The regional differences in the implementation of the BoD also influenced the church-planting process. The Woodworth’s were trained in church planting in Minneapolis by two openly LGBTQ clergy. That training included specific instruction on starting churches that were open, affirming, liberal and progressive, “and that helped us imagine what could be possible here” (Andy).

Our vision for a long time was, ‘What if you could have a church beyond the battles?’ Our formation as clergy in the Methodist Church was so enmeshed with that struggle, and like, ‘Who’s on what side?’ And we were like, ‘What would it look like for church to just exist like we have an inclusive church?’ (Anjie)

Though NC was intentionally open and affirming, the Woodworth’s initially chose not to join the RMN because they envisioned having “a church beyond the battles.” Here we find another instance of creative conformity – embracing true inclusivity without taking an explicitly resistant institutional stance. This choice was informed by their formation as clergy in the UMC, which they view as overly enmeshed with the struggles over LGBTQ inclusion. The Woodworth’s wanted to find out what it would look like for a church to simply exist as an inclusive church without making a statement that would engage them in the culture wars of the denomination.

Their goal was instead to focus on “living out church” that wasn’t merely affirming, but foundationally embraced all people. A theology of unconditional love has helped guide the entire visioning process: “We did a lot of theological work about framing why this is important. Why loving people as you love yourself [is important]. If you believe in the idea that God created people, you believe God created them as they are. That’s constantly interwoven in everything we do” (Anjie). As a result of this love-centered process, NC developed radically inclusive marketing verbiage and a tag-line that states, “All love. No B.S.”

We’ve had hetero couples come to us for counseling and for marriage and we’ve had to be like, ‘Cool, we’re totally down, but you gotta get someone else to marry you legally.’ (Anjie)

If we did it by ourselves, they would just pull us, done, there goes the congregation… Everybody’s watching all the things to bring people up on charges… And our congregation was really clear that they did not want us to be on the line that way. So I’ve actually feel like that’s one of our hardest struggles, is wanting to push a little harder and they are like, ‘Please don’t leave us.’ (Anjie)

The most visible area of the Woodworth’s creative conformity is in their 2016 decision to not perform weddings. It is conformity to the BoD because within this act of moral agency, they are complying with the rule to not marry same-sex couples. Yet, choosing not to officiate even heterosexual weddings is a creative means of non-cooperation with one of the primary functions of UMC clergy. The Woodworth’s stopped officiating weddings when they got to NC and realized they could decide for themselves what moral agency would look like around the decision to perform same-sex marriages. They questioned how overtly they wanted to resist, and whether instead of overt resistance, they would consider “side-stepping.” The Woodworth’s ultimately decided to side-step the rule that prevents them from marrying same-sex couples by deciding not to marry any couples. Doing so acknowledges the risk and vulnerability involved in openly flouting the injunction against same-sex marriages: “If we did it…they would just pull us, done, there goes the congregation” (Anjie). The Woodworth’s congregation members have also made it clear that they do not want to be exposed to that risk. That added layer of moral law – pressure from the congregation to conform – continues to constrict the Woodworth’s ability to live out their activism at full throttle.

Andy and Anjie describe the decision not to officiate weddings as one of their hardest struggles in ministry, demonstrating the dianomous nature of the constraints around their behavior. While Andy and Anjie want to “push a little harder,” their congregants, who do not want to risk losing them, are asking them to restrain themselves. Further, the congregation has claimed that it does not want the Woodworth’s to put their family stability on the line, due to the fact that they are at risk of losing their jobs if they were to perform a same-sex marriage.

Andy and Anjie often joke about what they would do if they were fired for performing a same-sex marriage. Andy says he’s considering growing tomatoes on his family farm or selling insurance.

Stage 4: Neighborhood Church Phase 2 (Post-GC 2019)

The GC 2019 decision pushed the Woodworths resistance even further and to consider what it might look like to leave the UMC. Directly following GC 2019, the pastors led a congregational discussion about how NC would respond to the outcome of the GC. And for the first time, they framed their actions in terms of resistance. The Woodworth’s had gotten to a place where creative conformity was replaced by undeniably non-conformist choices.

We were like, ‘OK, screw this,’ and we became Reconciling and aligned with Methodist Federation for Social Action….It was kind of like, let’s do this just to make a public statement: We’re on this end of things and this decision doesn’t get to stand for us. (Andy)

It was more of an F.U. to the institution, like ‘Oh, if this is how we’re gonna play, institution…’ (Anjie)

Anjie in particular is now very tired of the “middle line” path that she has been on. But though she has decided to follow her understanding of the Gospel of love and ignore the constraints in the BoD, her actions are now constrained by her congregants, who, while they lean progressive, do not all support leaving the denomination in the event that the GC 2019 decision is carried out. Anjie did state, though, that if there is no move toward inclusion at the May 2020 General Conference, NC’s board has stated that they are “done waiting” and that “something’s gotta give.”

There remains of course the constraint that NC’s property is owned by the UMC, and if NC were to leave the denomination, the church would risk losing their sanctuary, administrative offices, classrooms, and community spaces, which recently underwent at $3M renovation. Nonetheless, Andy and Anjie are beginning to strategize about what an exit could look like, not just for NC, but for all the other progressive UMC congregations who are no longer interested in being forced to act as moral agents under such constrained circumstances.

I’ve said to some congregation members here, ‘If you want us to marry you, we’ll be there.’ I’m ready to do it. (Anjie)

In the current post-GC 2019 era, Anjie states she’s finally ready to take the risk of officiating same-sex marriages: “I’m ready to do it. And wouldn’t necessarily make a huge deal out of it. Cuz most people don’t want to be a political statement. They just want to get married and live their life.” Andy stated, though with more hesitation, that he would, too. “I think,” he said, “I really don’t care what happens. I mean, I would not like the unpleasant experience of being called up on a charge, but there’s a very small likelihood if you don’t make yourself a public example.”

At each stage of their ministry, questions arise as to the level at which the Woodworth’s status as white, well-educated, straight, married pastors has influenced their freedom to make certain choices. It is likely that had any of these variables been different, they would not have felt the freedom or safety to voice even the least resistance to the UMC’s policy. Similarly, the fact that the Woodworth’s are married to each other and have had a partner in activism their entire careers has no doubt served to bolster their individual efforts. This is not mentioned to diminish the impact or validity of their work, but to highlight again that moral agency and activism are complicated, that no act is without its limitations, and that all moral agents are variously impacted by power and privilege.

An Open Door for Would-Be Activists

What I hope to demonstrate with this project is the idea that moral agency, and by association, activism, is complex and dynamic and inextricably connected to the constraints that thwart its realization. Thus, there is no such thing as “perfect” activism. It is therefore dangerous to uphold the kind of overtly resistant action that makes its way to newspaper headlines as the only form of legitimate activism, because it limits the imagination of those people who might wish to be involved in social change but have other commitments that influence their level of risk-aversion. Attending to the varied circumstances in which would-be activists find themselves opens the conversation to new voices and forges new pathways for resistance. This more nuanced and inclusive approach to activism creates space for and honors those whose work is more subtle such that everyone can imagine themselves as an activist.

If you would like to learn more about how to engage in social justice activism at any level – from personal to institutional to political – head over to Effective Activist today.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Reverends Andy and Anjie Woodworth for graciously inviting me into their space to interview them for this project and for allowing me to use Neighborhood Church’s photos. Thanks also to the members of Neighborhood Church for their warm welcome to their worship celebration.

Want to know more about this author? Click here!

Footnotes

- Timothy Williams & Elizabeth Dias, “United Methodists Tighten Ban on Same-Sex Marriage and Gay Clergy,” The New York Times, 26 February 2019.

- Elizabeth Bucar, “Dianomy: Understanding Religious Women’s Moral Agency as Creative Conformity,” Journal for the Feminist Study of Religion, 78, 3, 2010, 662-686.

- Ibid., 662.

- Ibid., 680.

- Ibid., 680.

- Ibid., 682

- All quotes by the Woodworth’s were gathered during a private interview conducted by Jessie Washington at Neighborhood Church on October 10, 2019.

- Ellen Ott Marshall, 1 November 2019, PowerPoint Presentation.

- Williams & Dias, 2019.

- David Nuckols, “Commission on a Way Forward,” 16 March, 2018, PowerPoint Presentation.

- Williams & Dias, 2019.

Amazing post! I’m very pleased to learn such brilliant piece of article. I appreciate your hard work. Thank you for sharing. I will also share some useful information.