From Sunher Singh Taram Library, Kachargarh, Dhanegaon.

“That which is lost will be found/and the one that is found/ I do not want to lose,” remarks a poet – Prakash Sallame, one of the many Gond activists, artists, and writers working towards the conservation of adivasi languages, culture, and heritage, in India.1 This essay explores rarely studied aspects of Gond culture: uses of multiple scripts as sites for exercising moral agency in the language primers created by the community.

Thus, this essay considers a particular multi-lingual language primer, which has been designed to teach Gondi language in the classroom as its protagonist and a moral agent in its own right.

The Gonds are one of the indigenous groups of India and have for long been associated with the ideas of “backwardness” and “illiteracy” in popular discourses and culture. It is significant to underline the literary production within and by the Gond groups to challenge these misrepresentations.

I specifically write about the agency to express claims of autonomy, preservation of tradition, and re-imagination of an alternate future for the community as it registers on this Gondi-language primer. This primer is a product of the robust cultural production that accompanied the religious standardization among the Gonds. This has worked to establish an organized adivasi religion called Gondi Punem or Gondi Dharma since the 1980s. Numerous literary and religious cultures have ensued due to this collective re-invention and refashioning of the self and community. Amongst the literary materials, various projects are undertaken at multiple levels. This essay illuminates the interplay of Gondi with various other languages, their strained relationships, and their role in asserting local knowledge.

In this imaginary, Gondi language (among many others) appears as a key site for creating tradition and community. This collective reinventing through language is an illustration of the negotiation of constraints faced by the community. Script-making, thus, appears as a means for conserving tradition and community.

Model of Moral Agency Under Constraints

In the context of script-making amongst the Gonds,

Moral agency is the capacity to conserve one’s personhood in the face of the conditions that are adverse, even inimical, to it.

The conditions that inhibit the exercise of freedom are constraints. Thus, moral agency is contingent on the constraints faced by the agent. The following exploration of agency within a language primer for Gondi language shows how the nature of constraints governs the movements in which a possibility of agency might appear. The lives of the indigenous groups (called Adivasis) in contemporary central India are caught within multiple political and religious forces. While constructing the “tribe” as a foil for the modern country the adivasi group had been rendered ahistorical in popular memory by the Indian state. The administrative interventions do little to counter this. They, in fact, reify the constraints on livelihood and knowledge of the adivasis. How does one break out of a canvas, or emerge ebullient out of a fossil, when other sides seem spaces of en-framing? For example, the very idea of a script is inimical to adivasi languages, which are oral in nature, rich in visual symbolism, and rhythmic in sound. However, the idea of script gained relevance in independent India as much of the nationalist discourse was based on linguistic identities. The languages without a script, many of which were adivasi languages, were either identified as the ‘dialects’ of other dominant languages or came to escape details in the Census.

The following example of Gondi language primer illustrates how constraints are first appropriated, and then re-deployed towards an alternative end. By inserting a cultural, visual archive from the Gond lifeworld, a Gondi language primer creates a space for its traditional knowledge system within modern pedagogic systems of modern India. The moments of agency are in and at the intersections of opposing ideas and worldviews.

How do the complex life-worlds of adivasis find representation in the script – a written form inherently systematized and scientific in nature? Or conversely, how does the Gondi-script attempt to mythologize the genre of the script while trying to reverse the processes of modernization? How are constraints navigated and moral agency exercised through various explorations on language and literature? In this context, the scientific and mythological sit together and playfully jostle each other for representation.

Gondi Language and Literature

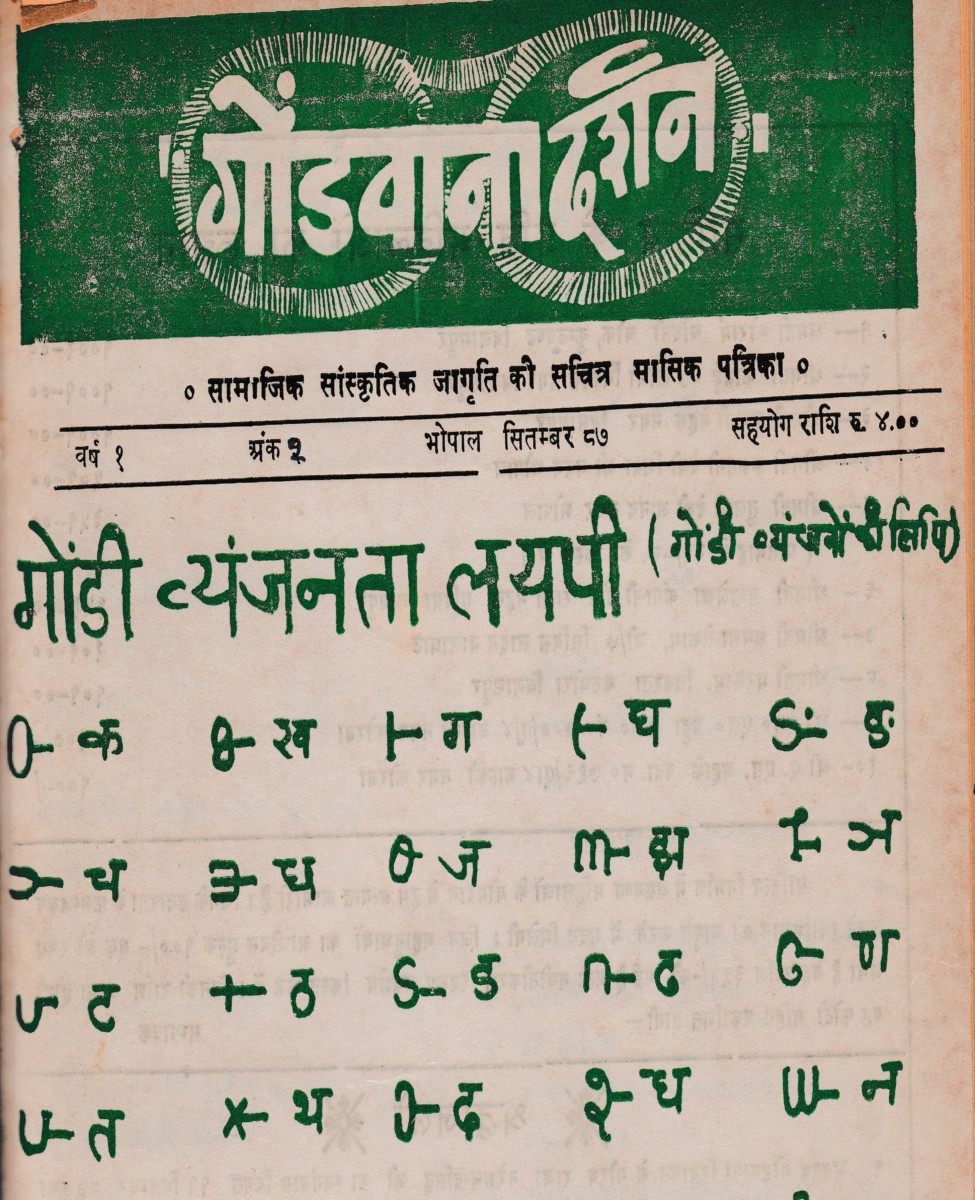

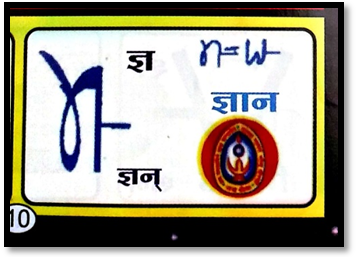

Gondi script appears in Punem’s prints, posters, clocks and calendars, language-learning materials as a language of tradition, history, and political imagination. In this context, Gondi is not a language of communication, a carrier of meanings, or a set of symbols. It is a means through which both the past and future are woven in together. It sits together with the objects of sacred importance in the new imaginary i.e. an illustration of the globe, standardized deities of the movement, and historical figures of the Gond community. The use of Gondi language in the primers, thus, is remarkably similar to the use of sacred objects in the material culture. Each object is representative of history. The use of Gondi script, in these materials, then asks what it means when a language comes to be visualized in a unique script and is placed along with the objects of sacred importance in the representational materials merging out of the movement.

First, there are poets who write about the issues of Gond identity, language, and culture. The most published poets among them – Bhujang Meshram authored poems both in his native language Gondi as well as in Marathi, which is the dominant language of the region he belongs to. Meshram published two poetry collections in Gondi, but later shifted to the use of Marathi in his later works.2 In spite of having published a range of literary and critical materials in Marathi language, Meshram suggests that Marathi literary organizations are paternalistic towards adivasi and asks, “That our adivasi friends have to write in languages other than their mother tongues – is this a sign of helplessness within Indian literature or an attempt to protect the dominant languages?”3

While disavowing ties with literature published in Marathi language Bhujang Meshram creates a space for his voice in the poetry of Native American writers like Scott Momaday, Joy Harjo. While writing about placing himself in the genealogy of the transnational, indigenous poets he writes, “Rather than writing in English in order to reach an international audience, it is important that the experiences in our poetry (that of adivasi groups) resonate with the experiences of these peoples.”4 While the issues and themes of Native American and African Poetry are seen as a cultural resource for Meshram, he translates a few of them – namely Joy Harjo, Scott Momaday, David Diop, Pitika Ntuli, in Marathi. Meshram situations himself in this mapping of transnational indigenous writers – albeit in the Marathi language! The collective experiences and memories of the ones historically marked as “tribes” are pulled into the Marathi language – a language of paternalism.

The second literary register makes up cultural and political writings by the leaders in the project. Aimed towards mobilization within the community and financially sponsored by various revivalist groups, these set of writings standardize Gondi language, script, and religion. One of the revivalist leaders – Motiravan Kangale, who is known as the dharamguru i.e. religious teacher of Gondi Dharam/Gondi Punem within the movement, authored multiple books on language and culture of the Gonds. Kangale was also one of the founding and long-serving member of Akhil Gondwana Gondi Sahitya Parishad (All-Gondwana Gond Literary Academy) and undertook two kinds of literary projects – first his book ‘Pari Kupar Lingo Gondi Dharam Puran’ (2011) combines religions of the Gonds, and prescribes the customs and ways to practice them. This work of Kangale is so central to the new imaginary that after his demise in October 2015 two statues of him were installed in Kachargarh – the most important pilgrimage site for Gondi Dharam. One was a bust of him and another statue of him holding Gondi Dharam Puran. As we see in the photograph of the second installation, Kangale’s installation is sculpted in a gesture of walking and holding the religious book in his one hand. Many in the movement hail him as a scholar and religious leader of the community. His book is repeatedly referred to in the writings of other activists and leaders in the movement.

The second set of writings by Kangale standardizes language and its users – ‘Brihant Hindi Gondi Shabdkosh’ (Comprehensive Hindi to Gondi Thesaurus) – which was published in 2011 and ‘Sundhavi Lipi ka Gondi mein Udhawachan’ (Deciphering Indus Valley Hieroglyphics as Gondi Language), which was published in 2002, deciphers the hieroglyphics on the artifacts found in the Indus Valley Civilization’s archaeological sites. The choice of language for the materials is yet again a matter of deliberation. In his introduction to ‘Brihat Gondi-Hindi Shabdkosh’ (Comprehensive Gondi and Hindi Thesaurus), Kangale describes how he replaced his first five-volume Gondi language dictionary project with a Hindi-to-Gondi thesaurus. Mainstream literacies are instrumentally deployed for the consolidation and spread of the Gondi language. A standardized language and literature enable a collective-invention’ of the community.

The third and the most dynamic register – to which the protagonist of this essay belongs, is that of mass-produced materials. Language primers, booklets of devotional songs, posters and calendars belong to this group of locally mass-produced materials. As the revivalist narrative is retold and reconfigured for specific geographic and cultural contexts, multiple variations appear and are performed in this register. Some of the language primers use Marathi and Hindi language in the Devanagari script along with the English language in Roman script to explain Gondi language and grammar. The mainstream languages of dominant traditions, in this context, get instrumentally deployed for the spread of Gondi language. In one such primer named Gondi Bhasha Pahada (Gondi Language Primer)5, a clan deity – Persapen, is used to represent one of the letters in the Gondi alphabet. This crystalized clan deity is also a symbol of the Gond Religion, which appears on altars at household shrines and in public spaces, religious posters used in rituals, and in political pamphlets. When Persapen’s image appears in the primer, the symbol is given the status of knowledge. A distinct cultural archive – representative of Gond community’s culture and knowledge, finds a place in modes of modern pedagogy. Despite being a modern genre not local to the tradition, this local attempt to conserve a vulnerable language reshapes the genre of the modern alphabet from within.

This example is significant because it shows an attempt by a marginal system of knowledge to find a place in the modern pedagogical apparatus. While a place for traditional knowledge is being claimed in the literate system, the norms of modern education are also deployed. Paradigms from dominant cultures – both local and transnational, are modes of re-imagining traditional knowledge. This example makes us think of ‘moral agency under constraints’ as contingent on specific context and location – the act of having a language primer based on the modern mainstream model might not appear as an act of agency – but, this primer subtly inserts the local body of knowledge, and thus reshapes the dominant tradition from within.

These multiple efforts to standardize distinct Gondi language, script, and literature even though, Gondi language and scripts usually depend on other languages in public spheres. Gondi is both a language of poetry and ritual transformations, a symbol representative of vulnerable knowledge traditions but also one that moulds itself to the modern forms of pedagogy. That Gondi flourishes using the dominant languages, and yet, refashions itself and others is not a sign of its collapse. Instead, it is flourishing along with, and using, other languages signals its malleability and vitality. In these various attempts to conserve culture and languages, dominant modes and media are used. The meanings of the resources and modes used are continuously re-created, thereby allowing the agency to be malleable. Moral agency, then, is this malleable capacity to conserve personhood using resources available at that moment and time.

Want to know more about this author? Click here!

Bibliography

Bhagdiya, Chandrabhan Singh. Gondi Bhasha Pahada, (Ghansour, in Madhya Pradesh: Rani Durgavati OffsetPrints, 2017

Kangale, Motiravan. Pari Kupar Lingo Gondi Punem Darshan. Nagpur: Tirumaay Chandralekha Kangali Publication, 2011. Print.

— Brihat Hindi Gondi Shabdkosh. Betul. Akhil Gondwana Gondi Sahitya Parishad, 2011. Print.

— Saundhawi Lipi ka Gondi Mein Udwachan. Nagpur: Tirumaay Chandralekha Kangali Publication, 2002. Print.

Meshram, Bhujang. Adivasi Sahitya ani Asmita Vedh. Pune: Lokvandhmaya Gruh, 2016

Sallame, Prakash. Koyaphool: Kavita Sangrah. Chandagarh: Akhil Gondwana Gondi Sahitya Parishad, 24 February 2001.

Footnotes

- Prakash Sallam, ‘Harivile, Sapdale’, in Koyaphool: Kavita Sangrah (Nagpur: Akhil Gondwana Gondi Sahitya Parishad, 2001), 23.

- Meshram, Bhujang, Adivasi Sahitya ani Asmita Vedh (Pune: Lokvandhmaya Gruh, 2016).

- Ibid., 89

- Chapter 3: Adivasi Sahityachi Disha, 57

- Chandrabhan Singh Bhagdiya, Gondi Bhasha Pahada, (Ghansour, in Madhya Pradesh: Rani Durgavati Offset Prints, 2017).

- Ibid., 10