It is difficult to find an exact date when the veggie noodle first came into being, but the veggie noodle seems to have peaked in popularity after 2010. There is growing reference to “veggie pasta” on Twitter only after 2010 and “spiralizer” and “zoodle” only begin to appear on Twitter in 2010, all of which is suggestive of a peak year in popularity. Veggie Pasta and Spiralizer only started to have accounts on Facebook in 2014 and 2017, respectively. On Facebook the veggie noodles that are the focus of this research paper first appeared in late 2015. “Zoodle” however, a type of veggie noodle that is short for zucchini noodle, first appeared in 2012 and 2013 on Facebook. When searching for a definition of “veggie noodle,” I came across the dilemma Corrado Barberis warned of in his “Encyclopedia of Pasta” when he talked of the uselessness of searching for a definition of pasta—no scholastic dictionary had a definition of “veggie noodle” (Vita 14). The veggie noodle, being unrecognized on Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster, is defined on HuffPost as a “standard vegetable” sliced into “noodle-like spaghetti shapes.” It has been a growing trend that is used as an alternative for what people think of as carb-loaded pasta. Traditional pasta has many different shapes, thousands even, and veggie pasta is trying to mimic these shapes, having one called “veggiccine” now as a clear reference to “fettuccine” (Cece’s Veggie Co). The advent of the veggie noodle interests me because due to its youth, it is a topic that has not yet been broached in research, so hopefully my study will pave the way for future studies on this subject. Noodles are taken for granted so often in what they can tell people about human interactions and various cultures, making them underappreciated edible cultural artifacts, and veggie noodles get even less attention than the average noodle. Veggie noodles are even newer than radiatori as a noodle, which only became invented sometime between World War I and World War II (Hildebrand and Kenedy 206). Past studies of food have shown that nationality affects peoples’ tastes and perceptions of different types of food (Dean et al 2007). Sociologically, the cuisine of some countries is unthinkable to eat, much less serve, in other countries, such as the taboo of insects as a form of cuisine in most European countries and the U.S. In this study, I seek to find if Americans and Italians react differently to the idea of veggie noodles in place of traditional noodles, thus exploring food choices through a cross-cultural comparative study. I hypothesize that there will be a smaller proportion of Italians than Americans willing to replace their typical noodles with veggie noodles in dishes.

The reasoning behind my hypothesis goes as follows: Italy and the U.S. have different prioritizations of food and tradition and differing degrees of obesity. Italian culture is heavily food-centered, more so than American culture in that life seems to revolve around food in Italy. Italians typically have long familial meals while Americans have embraced the fast-life in that convenience is prioritized over connecting socially and bonding with others. Italy is even the home of the proud founder of the Slow Food movement, Folco Portinari. The Slow Food movement quickly became an international movement after its inception and is meant to combat the growing spread of fast food, spreading but not deviating from its original purpose which was to reject the fast food practice that Portinari saw as taking away from years of Italian tradition. The Slow Food movement’s manifesto, written by Folco Portinari, views fast food, which is the embodiment of “Fast Life,” as an “insidious virus” that “disrupts our habits, pervades the privacy of our homes and forces us to eat Fast Foods” (SlowFood USA). Different countries’ branches of the Slow Food movement all share the same manifesto it was built upon. Not only is Italy the birth place of the Slow Food movement, but it also has a stronger attachment to tradition than the U.S. and most European countries today, hence saints’ days and harvest festivals that harken back to Italy’s peasant tradition, the continued honoring of the ritual of family gatherings around a meal at the kitchen/dining room table, the strong emphasis placed on fresh high-quality local produce, and the visiting of small family-owned businesses and local shops based on time-honored artisan traditions (Dunnage 3). Italy has also been shown to be the European country that displays the least amount of interest in veganism and one of the main selling points of veggie noodles is that they act as a vegan-friendly substitute to traditional pasta. Dairy and eggs are also staples of Italian food, serving as the main ingredient in many dishes including traditional pastas, so Italians with their stronger attachment to tradition may be even less likely to give a positive response to veggie noodles because it could appear as if it is trying to supersede the traditional Italian diet (Vegconomist, 2019). The U.S. is constantly progressing and evolving, and though change can be a good thing, change also inherently means a departure from the status quo, or in other words, tradition, so the U.S. appears as if it is less attached to tradition than Italy. The U.S. has also been around for a much shorter period of time and so its traditions are less strong and sturdily in place because it has not had as much time to strengthen them as Italy has. Another reason I hypothesize that the United States will have a larger percentage of positive responses toward veggie pasta than Italians is because the United States has a much bigger problem with obesity than Italy does. Italy is ranked as having one of the lowest obesity rates out of the OECD countries, which consists of some European countries, Korea, Canada, and the U.S, whereas the U.S. has the highest obesity rate out of all of these countries (OECD). Since veggie pasta is a trending health fad and there is such a strong focus on obesity in America, Americans may be more likely to jump on the bandwagon and try veggie pasta because of the urge to not become obese. This study I am conducting could test the strength and resiliency of tradition in Italy today because veggie noodles are a relatively new development that differ from the traditional noodles made of flour that typically go into Italian cooking.

In order to conduct this study of cross-cultural comparison, I employed the survey technique and textual analysis. The reason I chose the survey as my method of study is because surveys tend to give larger sample sizes due to the ability to widely disperse them. Respondents in this survey were made anonymous, so as to avoid response bias. I only made the survey two questions because people are more incentivized to take a short survey than a long survey, but I also gave the respondents the option of elaborating on their answers with a comment at the end of the survey. I chose very carefully how I would phrase the questions I was choosing to ask them so as for the answers to go toward answering my underlying research question of whether there were differences that could be shown in Italian and American cultures through responses to the veggie noodle. The two questions were verbatim, “Did you grow up in the United States or Italy?” and “Are you ok with replacing pasta with veggie noodles in dishes?” The possible answers one could give to these questions were either “United States” or “Italy” and “Yes,” “No,” or “It depends.” I phrased the first question the way I did because I wanted to ensure that the person grew up in one of the countries and if I was to say “born” instead of “grew up” the person might not have been in the country during the most formative identity-shaping years of his/her life and would not necessarily have been immersed in the culture. The second question I used “replacing pasta” instead of “replacing noodles” because the sample of people I am studying either grew up in Italy or the United States, both of which are in the Western hemisphere, and people in the Western Hemisphere tend to call noodles “pasta.” I used two of the most popular active social media sites, Facebook and Instagram, to reach out to people on completing this survey. I managed to find many Facebook groups consisting of people in Italy in an effort to gather as many Italians as I could for the survey, however I had to be approved to join these closed groups first by the administrators of the groups. Upon approval of my requests to join, I shared the survey on “ITALIA! TU SEI LA MIA PATRIA!” meaning “ITALY! YOU ARE MY NATION!” and the group page “Italian Food & Recipes,” sending it individually over Facebook Messenger and Instagram to many Italians that I found in these groups and in my social media feed, as well. The standard message I would put on group pages was “Ciao a tutti!!! I’m doing a research project and would really appreciate your answers. It’s just 2 questions that are 2 quick clicks. https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/358CWM6. Thank you so much/molte grazie!!!” The message I would send privately is similar in dialect but more personable, being “Ciao! Possi prendere il questo sguardo, per favore? È per la mia classe e è solo due domande https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/L9P6MY2?.” I opened the survey to the public on August 6thand closed it on August 9th. I used textual analysis to find reasoning behind my survey results.

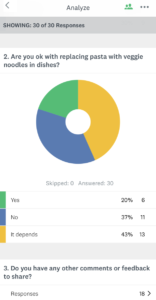

My survey results showed that thirty people in all completed the survey. 70% of the respondents, 21 people, were from the United States and 30%, 9 people, were from Italy, despite efforts to get more Italians to take the survey. Six people, approximately 20% of respondents in total, responded positively to replacing traditional noodles with veggie noodles. Eleven people, approximately 37% of respondents in total, responded negatively to replacing traditional noodles with veggie noodles. Thirteen people, approximately 43% of respondents in total, responded neutrally to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. Approximately 44.4% of Italians responded neutrally to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. Approximately 33.3% of Italians responded positively to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. Approximately 22.2% of Italians responded negatively to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. There was a different trend for American respondents, though. Approximately 42.85% of Americans responded neutrally to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. Approximately 14.28% of Americans responded positively to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. Approximately 42.85% of Americans responded negatively to replacing pasta with veggie noodles. The Americans and Italians did not differ so much in the neutral department, but they seem to differ dramatically in the positive and negative departments. One respondent from Italy commented that “Italy is a more simple life” with his/her answer of “It depends,” which I interpret to mean that Italians will do as they do, meaning they may do it and they may not depending on what happens in life. Another person from Italy commented with his/her answer of “It depends” that he/she would “replace pasta with veggie noodles only if cooking for a weekday meal or on any normal day,” but that he/she would “use normal pasta if wanting to invite friends at home for dinner or for special occasions” or “festivities” or “if wanting to prepare traditional foods,” which I found to be the most interesting of answers because of what it could show culturally behind these neutral answers, which were the majority of answers. The comment seems to show that the Italian would not use veggie noodles if trying to impress, but would if not trying to impress. I find it ironic that he/she will replace pasta with veggie noodles to likely impress with his/her figure when company is not around and if company is around he/she will use just normal noodles to impress his/her guests, so the two different forms of pasta would be used for two different forms of impressing. Another aspect underlying this comment could be that the Italian would use “normal pasta” with friends because he or she perceives those around them to not like veggie noodles and thus, to have social acceptance, does not cook them. The respondent claims that he/she would not replace noodles in traditional dishes with veggie noodles, showing an importance the respondent places on tradition, since the person is willing to replace noodles with veggie noodles in certain cases for non-traditional dishes.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Though I was surprised by the results of this particular study, I am content with what the finding reveals about Italian and American culture. All of my reasoning led me to believe that more Italians would respond negatively to veggie noodles than Americans proportionately, but my findings show the inverse of this. Proportionately, more Americans respond negatively to veggie noodles than Italians. Only a small minority of Italians respond negatively to veggie noodles replacing their typical noodles in dishes. However, a large percentage of Italians respond indifferently or neutrally to the replacement of noodles with veggie noodles. This rather large percentage of Italians could be an indicator that many Italians are willing to let go of tradition in certain contexts. The use of machines when making pasta in Italy shows a shift away from the traditional making of pasta such as illustrated in “Learn to Make Pasta from a Nonna in Italy” and “How to Make Pasta Like a Badass Italian Nonna,” but using vegetables instead of flour to make pasta changes the main component of most pastas in Italy, acting as a much larger and obvious form of deviation from tradition. Only a minority of Americans respond positively to replacing noodles with veggie noodles. This percentage could lead to a few possible conclusions. One possibility is that Americans have not gotten any better at cooking vegetables properly than Lin Yutang remembers them to be and this calamity of cooking is why many Americans do not want to venture into replacing typical noodles with veggie noodles (Yutang 253). Or perhaps, more likely, a large percentage of Americans respond negatively towards replacing noodles with veggie noodles because despite many advertisements and encouragements to combat obesity in America, there also is a large influx of commercials, posters, and promotional speakers advocating for people to accept all body shapes and sizes—obese and skinny alike—thus possibly canceling out the effect ads on battling obesity would have otherwise. Non-response was probably the largest complication I experienced when conducting this study. Despite my best efforts in needling my way into the online Italian community in order to get more Italian responses to my survey, relatively few Italians partook in the survey. This complication could have been due to a number of factors, one of which could be news of a possible online scam spreading around in Italy, in turn making the Italians believe that I was a bot trying to hack their accounts or steal their information, leading to them not even opening up the survey link. Although, I cannot discount the possibility that I faced this complication with Italian strangers and not with American strangers because of a cultural difference, as well. Italians have long been documented to distrust others and my own recent experience could possibly attest to that, thus this pervasive cultural distrust could have led many Italians to not click the survey link out of suspicion of what it might be. In an effort to have a larger pool of Italians in my survey, I lost eleven Italian friends on Instagram simply because of my request in Italian for them to take the survey. This did not happen with American respondents, on the other hand. If my study were ever to be replicated by another researcher, a different result may appear with a larger sample size of Italians taking the survey. Future research could also explore the possible differences in responses towards veggie noodles, or other phenomena if the researcher so chooses that deviate from tradition, between different generations of Italians. In hindsight, I would have liked to add an age-range question in the survey to see if age could have played a factor at all, or if other factors were at work, with the overall results.

Works Cited

Bratskeir, Kate. 2017. How Zoodles And Spirals Will Change The Way You Eat Veggies. HuffPost. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/vegetable-noodles-are-going-to-change-everything_n_5112928?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAALLQ5-SzEPfP4zxAFKeIZvoGHdh_57ieELDl9LN3Ugw3Z-KaCeLJJGUw28Ssmbj3ax9-ymiSmQUhtJlRfXaTEWQblAvQOt6aJbTDI4MYMdxEgjCNvM7AaJxDo3XEnD546BglB9zJkLNxUNfuhUek2pyB9IkZrlc3Edi40OSpvjyK, accessed August 6, 2019.

Cavalli, Alessandro. 2001. Reflections on Political Culture and the “Italian National Character”. Daedalus 130: 119–137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027709, accessed August 9, 2019.

- Italy—Language, Culture, Customs and Etiquette. Commisceo Global Consulting Ltd. https://www.commisceo-global.com/resources/country-guides/italy-guide, accessed August 9, 2019.

Dean, M., R. Shepherd, A. Arvola, et al. 2007. Consumer Perceptions of Healthy Cereal Products and Production Methods. Journal of Cereal Science. Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0733521007001269, accessed August 4, 2019.

Dunnage, Jonathan. 2002. Introduction: Between Tradition and Modernity. Essay. In Twentieth Century Italy: A Social History. 1st edition Pp. 3–33. London: Routledge.

European Countries Most Informed About Veganism Ranked in Order. 2019. Vegconomist – the Vegan Business Magazine. https://vegconomist.com/studies-and-numbers/european-countries-most-informed-about-veganism-ranked-in-order/, accessed August 7, 2019.

Heath, Elizabeth. 2018. How To Make Pasta, According To Three Real Italian Nonnas. HuffPost. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/make-pasta-like-italian-nonnas_n_5b9bf0f8e4b013b0977a7d01, accessed August 9, 2019.

Hildebrand, Caz, and Jacob Kenedy. 2011. The Geometry of Pasta. London: Boxtree.

Lever, Charles James. Italian Distrust. Dickens Journals Online. http://www.djo.org.uk/indexes/articles/italian-distrust.html, accessed August 9, 2019.

OECD. Obesity and the Economics of Prevention: Fit Not Fat–Italy Key Facts. OECD: Better Policies for Better Lives. https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/obesityandtheeconomicsofpreventionfitnotfat-italykeyfacts.htm, accessed August 7, 2019.

Slow Food USA. Manifesto. Slowfood USA. https://www.slowfoodusa.org/manifesto, accessed August 7, 2019.

The Skinny on Veggiccine®. 2017. Ceces Veggie Co. https://cecesveggieco.com/2017/12/20/the-skinny-on-veggiccine/, accessed August 6, 2019.

Vita, Oretta Zanini De. 2009. Encyclopedia of Pasta. University of California Press.

White, Annette. 2018. Learn to Make Pasta From a Nonna in Italy. Bucket List Journey | Travel Lifestyle Blog. https://bucketlistjourney.net/learn-make-pasta-nonna-northern-italy/, accessed August 9, 2019.

Yutang, Lin. 1937. The Importance of Living: a John Day Book. New York: Reynal and Hitchcock.