Sarah Kim

Journal #1: Jjangmyeon

Jjangmyeon is a Korean dish that is also known as Black Bean Sauce Noodles. It is a Chinese Korean fusion dish that is popular in Korea and in the States. Jjangmyeon is a noodle dish with a thick sauce made of chunjang (a black/brown paste with a savory and sweet flavor), pork, and different vegetables like onions and cucumbers. Unlike most popular Korean dishes, it is not spicy. Unfortunately, I cannot handle spice very well. In fact, I rarely eat Kimchi because it is spicy. This is also a dish that is important to me and represents my family and cultural background. Jjangmyeon is a comfort food for me. Whenever I am feeling down, my parents take me to my favorite jjangmyeon restaurant. Surprisingly, eating this dish helps me feel better.

Moreover, I have good memories related to this food. It is Korean tradition to eat jjangmyeon after graduation. I still remember eating jjangmyeon as a family after my elementary, middle school, and high school graduations. They would congratulate my accomplishments and we would have many different and spontaneous conversations about life. This dinner is very special and meaningful to me. The times when I crave this dish, but cannot go to my favorite restaurant, I make the instant noodle version of this dish called, Chapagetti. When I am at Emory, Korean restaurants that serve this dish are a thirty-minute car ride away so during the semester, I see a lot of Chapagetti mukbangs. Mukbangs are very popular today. They are videos people upload on social media and Youtube of them eating specific foods. Some people to an ASMR version, in which I recommend listening to the video with headphones or earphones on. Some people may say that watching people eat makes them hungrier, but for me I feel better.

This dish has a rich history that started in China’s Shandong region. Jjangmyeon originated from zhajiangmian, which means “fried sauce noodles” in Chinese. China sent military men to Korea during the late nineteenth century and helped introduce different recipes. This dish was brought over to Korea during the Joseon Dynasty. However, it became popular after the Korean War. It was known for being a cheap dish. People of all classes were able to enjoy a small bowl of jajangmyeon after a long day of work or as a family treat. Its low and affordable price along with its savory taste helped make jajangmyeon a popular dish in Korea. Moreover, Koreans who come to the United States and start a jajangmyeon business attract many different Koreans in the area. These restaurants are little hotspots for many Koreans and Korean Americans to find people they can relate with and.a place where many can get in touch with their culture.

Jjangmyeon is also holds an important place of the Korean culture. Korea has a lot of holidays celebrating couples and singles. In the United States, Valentine’s Day, on the fourteenth of February, is a day when both. males. and females get the chance to confess their love to a significant other by giving them chocolates and roses. On the other hand, Korea made specific dates to commemorate these love confessions. Valentine’s Day in Korea is also on the fourteenth of February, but on this day only females give chocolate to the males as confessions. The following month, the 14 of March, is the romantic holiday called White Day. This is when the males give chocolate to the females in response to what they were given on Valentine’s Day.This leads us to the last event Black Day, or the Single Awareness Day, is on April 14th. This is a day to celebrate being single by enjoying jjangmyeon. It is interesting how the South Korean government created this occasion.

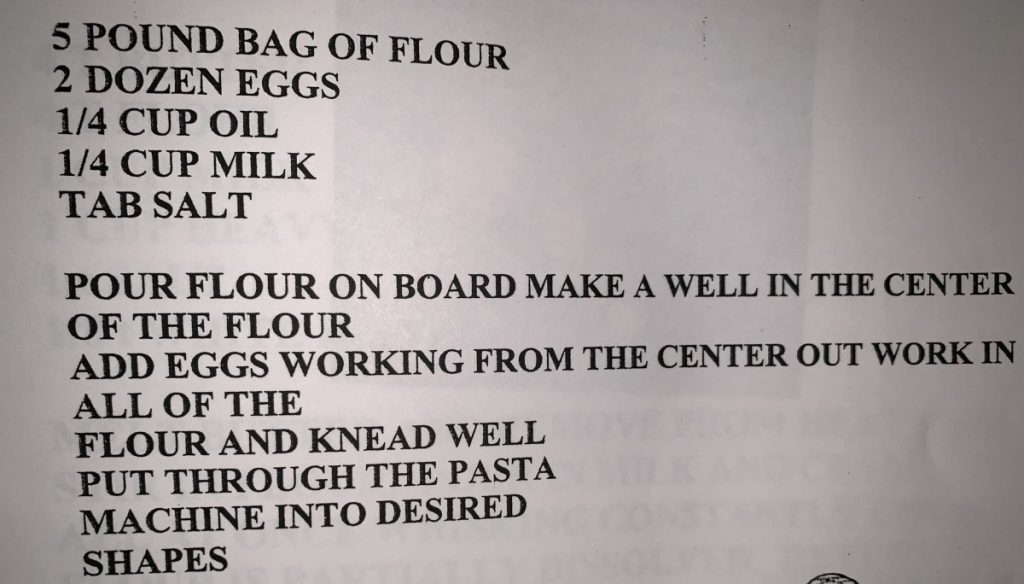

Recipe for Jjangmyeon

1 pound fresh jajangmyeon or udon noodles (or substitute a couple packages of instant ramen noodles)

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

6 ounces fatty pork belly, cut into large dice

3 ounces pork shoulder, cut into large dice

1-inch knob of ginger, minced

2 cloves garlic, minced

½ medium carrot, diced

1 large Yukon Gold potato, peeled and cut into small dice

2 medium red onions, diced

½ zucchini, peeled and diced, plus ¼ cup julienned zucchini

½ cup black bean paste (chunjang)

2 tablespoons sugar

Kosher salt to taste

¼ pickled yellow daikon, cut into half-moons (optional)

1. Bring a large pot of water to a boil and add the noodles. Boil the noodles for 8 minutes, until soft (just beyond al dente), reserve 1½ cups of the noodle cooking water, drain and rinse the noodles with cold water to cool to room temperature. Drain well and reserve.

2. While the noodles are boiling, heat the oil on high heat in a wok or large skillet until lightly smoking. Add diced pork belly and shoulder and render for 2 minutes.

3. Add ginger and garlic and saute for 1 minute, being mindful not to let it burn. Add carrots, potatoes, onions and diced zucchini and saute for 6 minutes, until the vegetables are softened.

4. Mix in the black bean paste, sugar, 1 cup of reserved noodle water and salt to taste. Cook for 7 minutes, or until the sauce has thickened and the potatoes are fully cooked. If you need to add more noodle water, do so.

5. Divide noodles into 2 bowls and top with warm sauce. Garnish with julienned zucchini and pickled yellow daikon. As an alternative, the sauce can be served over cooked rice for a dish called jjajangbap.

Adapted from https://www.nativetraveler.com/blog-main/a-taste-of-koreatown

ure of hand grilled lamb.

ure of hand grilled lamb.

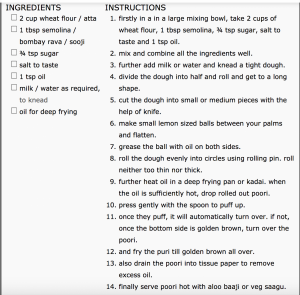

(My great-Noni Barbarina Galli and great-great Aunt Assunta making fettuccine)

(My great-Noni Barbarina Galli and great-great Aunt Assunta making fettuccine)