Matzo ball soup is of great importance to me, almost a spiritual experience, for a variety of reasons—first and foremost, there is its delicious flavor. There is nothing better than biting into a matzo ball of perfect size, texture, and density, with the right balance of spices. It is very easy to tell when a matzo ball has just the right ratio of ingredients and was cooked for just the right amount of time. Secondly, and in connection to the previous point regarding flavor, is the sense of home that a warm of cup matzo ball soup gives me. There is a reason that people call matzo ball soup “Jewish penicillin,” for there is nothing better for soothing a sore throat or cold than a warm cup of matzo ball soup, prepared just right. From my preschool through high school days, if I was home sick from school, my mom would offer me a cup of matzo ball soup. It became associated with ‘sick days’ for me, and as I grew older, she did not even have to ask me anymore if I wanted it, for she knew that it was the one thing I craved in that moment. When I came to college for the very first time and was hit with a severe cold during syllabus week of my Freshman year, my mom phoned Hillel at Emory—specifically, for their “Jewish Penicillin Hotline,” a special service offered by Emory’s Hillel (and Hillel’s nationwide) that caters to sick students, by delivering matzo ball soup to them at no cost. More information about Emory Hillel’s “Jewish Penicillin Hotline” can be found on their website (https://emoryhillel.org/jewish-penicillin-hotline/). I had the sense of warmth and of home upon sipping this cup of soup, feeling automatically better—despite my being several hundred miles away from home, my mother still had the ability to ‘take care of me’ via my favorite cure—matzo ball soup—thanks to Hillel’s program. On another note, matzo ball soup holds special meaning for me because of the connection that it has to my grandmother. My grandmother’s homemade matzo ball soup was my all-time favorite, and it wasn’t just the eating that ranked so highly but also the fact that we made it together which added up to a special bonding experience, —cooking in general was our main way of bonding. If it were not for my grandmother, I most likely would never have found the pleasure that I do in cooking and baking (anything) to this day. She had a natural talent for this and delighted in sharing it with me. This was a true inspiration. Although she is no longer with us, her lessons gave me the skills to continue her tradition and keep her memory close.

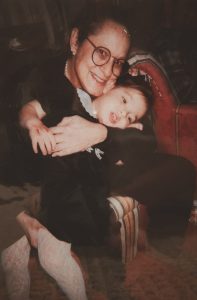

The two photographs that follow are linked to the meaning that matzo ball soup holds dearly for me. The first one is of my loving grandmother—the matzo ball master chef—and I, at my second birthday. The second photo is of the dish itself—matzo ball soup—which I tracked down from NPR’s website (https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/04/03/397213116/ahead-of-passover-learning-how-to-make-matzo-balls). I could not find a photograph of my grandmother’s matzo ball soup but note the dill that is in the broth—a major contributor to the broth’s flavor.

While my grandmother did not have a written recipe for her soup, years of observing and assisting—by being her “taste-tester”—taught me the optimal proportions of ingredients, and one day I made sure to write down everything that I had observed. Moreover, there are two key parts to this soup—the first one being the broth, and the second one being the matzo balls. Before making the matzo balls (my favorite part), she would make the broth, incorporating the following basic ingredients:

- FOR THE BROTH:

- 1 whole Amish chicken

- 1 tablespoon of vegetable oil

- 2 cups of water

- 4 medium carrots, peeled and diced

- 2 stalks of celery, diced

- 1 large onion, diced

- 2 cloves of garlic, minced

- 3 sprigs of dill, rinsed

- 3 sprigs of parsley, rinsed

- 1 teaspoon of black peppercorns

- KOSHER SALT (to taste, by the pinch)

First, in a large pot and over medium heat, she would sauté the carrots, celery, onion, and garlic, in the vegetable oil. Second, she would add the remaining ingredients, along with 2 cups of water, to the mixture in the pot. Next, she would place the lid on top of the pot, over medium heat, and let it reach a boil—the point at which she would turn down the heat to a simmer and do this for 30 minutes or so. In the meantime, I would help her out with making the matzo balls—my favorite part—which required the following ingredients:

- FOR THE MATZO BALLS:

- 1 cup of matzo meal

- 4 eggs

- 1 teaspoon of baking powder

- 3 tablespoons of vegetable oil

- 3 tablespoons of water

- 1 teaspoon of fresh dill, diced

- 1 teaspoon of salt

- FRESHLY CRACKED PEPPER

First and foremost, she would have me whisk together the ‘wet’ ingredients: the eggs and vegetable oil. Next, I would add the matzo meal, baking powder, salt, and a pinch or so of freshly cracked pepper into the mixture—and lastly, I would add the water. Then, it was time to wait, as we had to allow about 30 minutes or so for the matzo ball mixture to absorb the liquid and harden while in the refrigerator. Right about now, the soup is fully simmered, and it is safe to remove and shred the chicken. With the shredded chicken aside, the soup can be strained—thus, discarding the remaining solid ingredients, and the shredded chicken can then go back in. When it comes to making matzo ball soup, the broth is the most challenging part, as it requires a lot of tasting and modification, accordingly. Often, the measurements of salt and pepper have to be adjusted; thus, it is important to start off on the lower end in terms of quantity. One can always add more—otherwise, that is, if you add too much, it may be too late to fix. Moreover, once the broth is complete and you have allowed for the matzo ball mix to harden and absorb the moisture while being refrigerated, you can sculpt! On the side, you want to have a simmering pot of water, awaiting the sculpted matzo balls which are to be tossed in. Molding the matzo balls was always my favorite part of the process. Once they were all ready, in perfectly spherical balls, I would drop them into the simmering water, one by one, and set the timer for 25 minutes. My grandmother taught me that the longer you cook the matzo balls, the lighter they become. And it is all about preference in this case; I enjoy my matzo balls just in between dense and light. Once the timer had gone off, the cooking and preparation were complete, and the broth and matzo balls were ready to be combined! For longer lasting matzo balls, I would often watch my grandmother reserve some of the matzo balls in airtight containers and refrigerate or freeze them (for me to have later on), but depending on the occasion, this was not always necessary.

An additional factor marking the significance of matzo ball soup for me, is its origin in the Jewish culture and religion—one that my entire extended family has grown up following, and one which links us all together. Moreover, the Jewish religion has been a major part of my upbringing. Although matzo ball soup is linked to Judaism in general, it is most often eaten by Jews during Passover, as part of the Passover meal (or Seder). “The Jewish holiday of Passover celebrates the Biblical story of the Exodus, or the freeing of Hebrew slaves from Egypt. . .The Passover meal, known as a Seder, is all about remembering Jewish history. Much of the food is deeply symbolic. Matzo represents the unleavened bread the Jews ate while fleeing Egypt, for example, and horseradish is a symbol for the bitterness of slavery” (https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/04/03/397213116/ahead-of-passover-learning-how-to-make-matzo-balls). Furthermore, each component of the Passover meal has cultural significance to Judaism, as each symbolizes a concept relevant to Jewish history that has been taught and carried through Jewish tradition. Thus, matzo ball soup’s which uses only matzo meal —is in keeping with the Passover practice of eating only unleavened food. This is done because historically, was no time for bread to rise when the Jews left Egypt in a hurry; and the flatness of matzo is said to symbolize humility as opposed to arrogance. So matzo ball soup holds great symbolism for Jewish people during Passover, but I can eat it any day! It gives me all of the above: a sense of familiarity, of comfort, and of home, family, tradition, and religion.