When Dr. Raper spoke about questions pertaining to how we might talk about suicide, it reminded me of my role as a crisis counselor at the Crisis Text Line. During training, we learn to utilize a ladder-up approach concerning conversations surrounding suicide. Every individual who seeks help from the platform is asked the following questions:

- Are you having thoughts of suicide?

- Do you have a plan for how you would do it?

- Do you have access to the means to carry it out?

- Do you have a time planned for when you would do it?

At first, it felt weird to be asking individuals what their plan was to kill themselves because I thought it would exacerbate thoughts of suicide. However, there is a plethora of data demonstrating that this is not the case. Moreover, as I had more conversations, I realized that these questions instead helped individuals feel like someone was listening to their concerns and not avoiding their immediate troubles. They felt that someone was genuinely helping them through their struggles, rather than being scared to address their concern head-on due to the stigma surrounding mental health issues. Thus, talking about suicide actually reduces suicidal ideation, and enables improvements to be made in treatment.

Dr. Raper further spoke about self-stigmatization, or the internal shame, that people with mental illness carry within themselves. However, per my experience, within the South Asian community, it seems that mental illness is something viewed as a collective issue, in which the mental illness reflects poorly upon the family, rather than simply the sufferer. A lot of the stigma comes simply from a lack of understanding or fear.

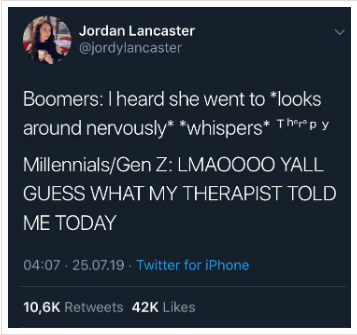

Furthermore, although there is conflicting evidence, there seems to be a decline in the stigma of mental illness, especially amongst young people. Many of us students are very vocal regarding how we are feeling mentally, yet there seems to be a disconnect between us and the older generation who are in positions of power running mental health departments at academic institutions (as I talked about in my post two weeks ago).

Similar to Dr. Raper’s points about stigma, there is a need for a safe and trusted environment to speak about mental health. Without such an environment, mental health illness, which was significantly exacerbated during this pandemic, cannot be addressed properly.

Because of the pandemic, a lot of us saw increases in our own mental health symptoms and conditions, enabling an increase in knowledge on mental health. As a result, I saw a change in mental health stigma at a classroom level after online learning had started. Professors became more agreeable with mental health excuses from class and extensions for assignments for mental health issues–something that professors would often want proof for (I’ve actually had a professor ask for proof that my cousin died my freshmen year when I requested an extension based on my mental health :/) beforehand.

The universal experiences many of us have shared, coping with the uncertainties of the pandemic–whether baking banana bread, making dalgona coffee, or going on walks–have enabled us to focus on mental health, and, unconsciously or not, reduce the stigma. These shared social connections have further led to increased resilience within our communities and emotional acceptance of others, which is incredibly valuable in an increasingly divided world.

What do you think could be done to reduce stigma related to mental health issues in academic settings or in the workplace? Because it seems that any attention being brought up about mental health in these settings is due to a fear of a “lack of productivity,” rather than an emphasis on people’s well-being.