The topic of death and dying is something I’ve researched before and take great interest in. The topic of death is so complex and mentally draining that talking about it makes me go through emotions. Last year, I took a course on this topic and gained much newfound knowledge, specifically regarding the dying process. In a way, death and grief are a cycle that we all experience, and this pandemic highlighted that.

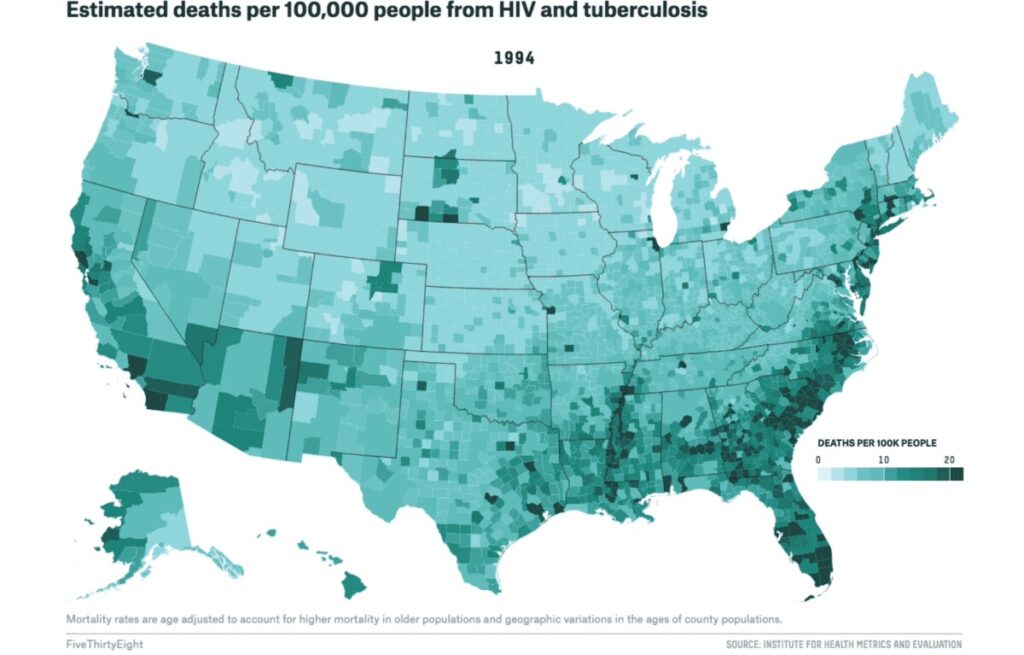

As COVID has gone on, we have become desensitized to death. Every life has become a statistic, with countries being in a pseudo-composition for who has the highest number of deaths. I think that the HIV/AIDS epidemic differs from COVID-19 in that people have less incentive to know the deaths and impact of the disease; specifically, with CIVID, anyone and everyone can become infected. With HIV/AIDS, only those who are exposed to it through sexual activity really focused and cared about the numbers and deaths.

I think a significant component of death is within the time range. Those with a life-ending diagnosis will have to grieve for a stretched-out period compared to someone who dies from an illness within minutes or days. Those who have to grieve for an extended period tend to go through (and possibly complete) the cycle of grief, which in itself is torture. Accepting that you are dying is not an easy pill to swallow. But in the end, we all technically know we will die. It creates the philosophical question, “If I’m going to die regardless, how does a life-ending diagnosis make me grieve my death more?” “Is it better to know when you’ll die or have it happen at any moment without knowledge?”