Background

William Shroeder, a 52-year old native of Illinois, was the 2nd recipient of a permanent artificial heart. In January 1983, he suffered from a massive heart attack, which severely damaged his heart and left him unable to walk a few feet without experiencing chest pain and shortness of breath. According to his family physician, if Shroeder received a transplant, the antirejection drugs would throw his diabetes out of control. Therefore, his  only option was an artificial heart, which on average costs $150,000 per patient. Four years after he received his artificial heart, Shroeder passed away.

only option was an artificial heart, which on average costs $150,000 per patient. Four years after he received his artificial heart, Shroeder passed away.

Case Discussion

The major dilemma in this case is whether or not our health care money should be spent on costly medical hearts, which are more cost than gain and only benefit a relatively small pool of people. Furthermore, could this money be better spent on early detection of disease and programs for preventative medicine?

According to the authors, “The bill for Will Shroeder’s operation ‘represents 790 days of hospital care equivalent to full treatment of 113 patients for an average stay of a week’ ” (Thomas, Waluchow, & Gedge, 172). Although the money it takes to treat one person for an artificial heart could clearly be used to save many more, a doctor cannot simply deny healing someone if there is a treatment option available, whether that option is extremely costly or not. The doctor has a duty to do no harm and to provide treatment to the patient. In fact by providing Shroeder with the artificial heart, the physician followed the three principles of beneficience, which according to Beauchamp and Childress are as follows:

- One ought to prevent evil or harm.

- One ought to remove evil or harm.

- One ought to do or promote good.

The authors of this case also go on to say that, “exotic medical technologies have offered us only marginal returns in reducing illness and premature death” Thomas, Waluchow, & Gedge, 170). However, the improvement of other factors such as better air, improved sanitation, and more conscientious lifestyles work just as well and provide benefits to a larger population.

Analysis

The authors suggest that we must stop and “weigh out the short term losses against the long-term gains” and decide if it’s feasible to treat someone (Thomas, Waluchow, & Gedge, 173). The authors continuously bring up the dilemma over whether we should treat someone who has a preventable disease such as diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association, with Type 1 diabetes, you inherit risk factors from both parents and an environmental trigger like exposure to a virus or even cold weather can trigger the onset of the disease. Type 2 diabetes has a stronger link to family history, but both types can be triggered by early eating habits.

However, we also have to think of the socioeconomic factors that cause people to have preventative diseases like diabetes. What if cheaply made processed foods was all that someone could afford to eat and that person could not help that they developed diabetes? Despite his diabetes, Shroeder was responsibly managing his diabetes and could not help that he had a heart attack. You would not deny someone who got into a car accident medical treatment even if it was their fault for being drunk and getting themselves into the accident. So how can we debate whether or not we should deny people of an artificial heart?

Conclusion

Ultimately, in my opinion, there is no decision to be made when it comes to saving a person’s life: you should just do it. I think that it is unfortunate that a medical miracle like the artificial heart could be so expensive and offer such little marginal returns. Thus, more money should be allocated to public health programs that focus on preventative medicine, research to cure these diseases, and the improvement of factors that affect our living conditions, so that we are not faced with costly medical procedures like the artificial heart.

Works Cited

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. N.p.: Oxford University Press, 2012. Print.

“Genetics of Diabetes.” American Diabetes Association. American Diabetes Association, 20 May 2014. Web. 20 Feb. 2015. <http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/genetics-of-diabetes.html>.

Thomas, John, Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2014. Print.

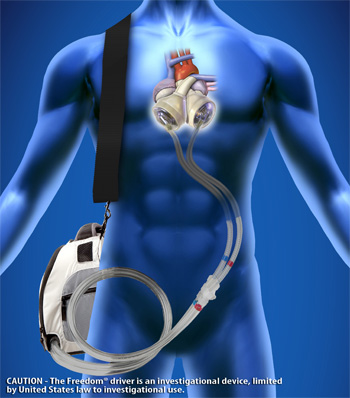

Image:

http://transplants.ucla.edu/images/heart/SynCardia/SynCardia_Freedom_Portable_Driver.jpg