Summary

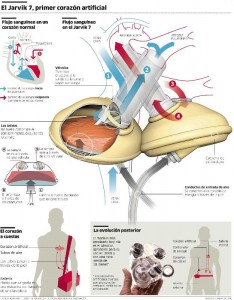

William Schroeder, a previously healthy man with an active lifestyle suffered a massive heart attack that left him with terminal arteriosclerosis. This led to Schroeder becoming the second person ever to receive an artificial heart. Humana hospital agreed to cover the costs of the transplant and even build a special house for Schroeder to stay in after his recovery was complete. The procedure was a success and Schroeder would seemingly live out the rest of his days without much discomfort, but things gradually took a turn for the worst, and Schroeder suffered a total of 3 strokes and eventually passed away after living 620 days with the Jarvik-7 heart in his chest (2).

Case Discussion

The primary moral dilemma discussed in the text is about the allocation of funding in healthcare. Should we spend exorbitant amounts of money on things such as artificial hearts that would only benefit a small percentage of patients, or should this money be better allocated to other programs associated with early detection and prevention that could benefit more people?

While I think this is an interesting issue to consider, I was particularly interested in Schroeder’s individual experience. Namely, I am concerned with whether the principles of nonmaleficence were upheld by Schroeder’s healthcare team. Beauchamp and Childress state these 5 rules about nonmaleficence:

- Do not kill

- Do not cause pain or suffering

- Do not incapacitate

- Do not cause offense

- Do not deprive others of the goods of life

Surely, by giving Schroeder the artificial heart, all of these rules were being upheld. However, after his first stroke, Schroeder was left with severely impaired speech and memory problems. The patients wife stated:

“I see it as more of a research experiment. The longer he lives, the more information [doctors] will get. Only for us it’s so hard sometimes.”

This brings up an interesting situation to consider. While doctors are upholding the first and last of the moral rules stated above, some might consider keeping Schroeder alive on the artificial heart as violating the second rule. We are given little insight into Schroeder’s mental state, but we are told that Barney Clark, the first to receive an artificial heart, complained to psychiatrists that he wanted to die on several occasions.

While I do not think it is any of the doctors intent to cause pain or suffering, one must think about who is benefitting more from the artificial heart, the doctors or the patient? The data being gathered from Schroeder’s experience could be invaluable to improving the procedure for future recipients of artificial hearts, but it seems that he is in considerable suffering without a hopeful chance for living a normal life. It would be interesting to read what was in the extensive consent form that Schroeder and his wife agreed to before undergoing the procedure. Furthermore, I have been unsuccessful in finding any studies that assess mental health of artificial heart recipients.

References

1. Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. “Nonmaleficence” Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. 150-193. Print.

2. Thomas, John E., and Wilfrid J. Waluchow. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Toronto: Broadview, 2014. Print.

I agree with you on the part that more research on the effects of the artificial hearts would have been more helpful in determining whether this procedure that doctors carried out can be justified morally. Had we given the findings of the research on the mental health of patients who received the artificial hearts doctors may be more hesitant to give this surgery. I believe that the quality of life is determined by the mental health of a person, and even though the physical discomfort might not have been so great for the first two years maybe, it would have surely affected the patient’s mental health. In this sense, the non-maleficence, one of the doctor’s moral responsibilities, might become questionable. In addition, I also agree with your question asking about to whom the artificial heart is beneficial. The wife mentioned in the interview that it’s more like a research for doctors than his husband getting treatment (1). If she felt it this way, then it might bring in the issue of manipulation that Beauchamp and Childress stated, by “swaying them to do what the doctors wanted” for the research purpose in mind even if the patient’s health was still considered or “by framing information positively” (2). It can definitely prolong the life, but is it the quality that the patient wanted? More than anything, I believe that the doctors need to find an alternative way or ways to saving a patient’s life than giving an artificial heart. Its cost, although covered by not the patient’s family, is not worth the quality of life he had lived in a house that he had to live in without a choice and with so many side effects and undesirable hemorrhages and strokes that the patient had to go through. Perhaps, this may be one of the cases that letting a patient die is morally justified. It sounds so miserable to be alive for the patient and even for the family members who watched the patient go through terrible things.

References

1. Thomas, John E., and Wilfrid J. Waluchow. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Toronto: Broadview, 2014. Print.

2. Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. “Nonmaleficence” Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. 150-193. Print.

The cost aspect of research is often something that is given very little attention in the United States. Because the US has a private health care system, many do not criticize the cost medical companies spend on things like research because they are simply a part of a capitalist system. Medical companies, like all businesses, have the right to spend money in order to maximize potential profits. In countries with socialized medicine, though, the conversation changes from what will bring in the most money to how will the most people be benefited in the best way possible. Medical research in the United States very much reflects the political climate and values that pervade American culture. Other countries, like in Western Europe, have socialized medicine which makes research and medical advancement much less profit driven. Medical care brings into question many business aspects people take for granted, because profits potentially could come at the cost of human lives.

You brought up an interesting dilemma in your introduction about allocating healthcare funds. How do we allocate so that we minimize harm and maximize beneficence? This particular case of the artificial heart brings up a debate that has raged for decades: Do public health policies or biomedical procedures benefit society more? The widely taught writings of British physician and medical historian Thomas McKeown (see his “Determinants of Health”) suggest that public health measures such as improved nutrition and living conditions can be more powerful and begin acting on disease before biomedical interventions. On the other hand, advocates of American biomedicine could argue that Mckeown’s theories only hold water for certain historical time periods in which infectious disease rates were high. But, what about chronic conditions such as heart disease? Preventative programs aimed at nutrition and lifestyle changes have shown to be effective at reducing heart disease risks, so it would seem logical to invest most of our money into preventing the disease if it is in fact preventable. However, other studies show that regardless of diet and lifestyle, patients may still get heart disease at some point in life perhaps from a genetic predisposition. Additionally, heart disease is currently an epidemic in the United States (one could argue is has become endemic) with the CDC citing it as the country’s leading cause of death. With both high incidence and prevalence of the disease, I think the most ethical thing to do in this case would be to combine methodologies of both sides to create treatment that simultaneously treats with food, exercise, surgical, and drug therapies. This would result in funds being directed to both aspects of chronic diseases, the preventable (and potentially reversible) side and the biomedical intervention side, hopefully having a synergistic effect in improving population health overall.