Background

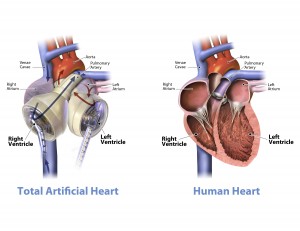

In 1984 William Schroeder became the second man in the world to receive an artificial heart transplant after suffering from terminal arteriosclerosis, and being largely bedridden after a massive heart attack. While everything may have seemed to be going fine post-surgery, within a few months Schroeder had suffered two hemorrhages, and went on to die on the 11th of November, 1985. Important to this case is the fact that the Humana Hospital, where he was admitted, agreed to pay for the $15,500 artificial heart system, while also supplying Schroeder and his entire family with free accommodations within the hospital, and on top of that, providing the patient with a specifically designed house tailored to his medical needs should he become well enough to leave the hospital. There is no denying here that Schroeder is, in a sense, a very expensive patient.

Dilemma and Discussion

The issue with Schroeder’s case, and with patients in similar rare medical circumstances, is that their medical expenses are staggeringly high compared to most procedures available. To make this issue even bigger, there is only a minute portion of the population that would ever be affected by his condition (50,000 in US, 5,000 in Canada). Now the question begs, is it worth it to allocate resources towards such procedures that would only benefit a small number of people? Or would that money be better allocated elsewhere, where the needs of the many would outweigh the needs of the few?

Medical care no doubt improves our lives, but there are numerous other types of social goods that can improve the lives of many, maybe to an even greater extent than medical care can. Discussed in the reading is the difference between “needs” and “wants”, where health is considered a basic need, and “wants are inessential to human flourishing, but add quality to our lives”. In regards to needs, I am in accordance with what was said in the reading, but regarding their definition of “wants”, I have a few things to say.

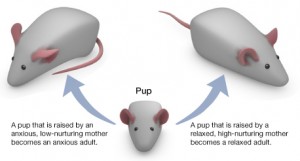

While I agree that wants add quality to our lives, I disagree whole heartedly that wants are “inessential to human flourishing”. Studies have shown that an enriched lifestyle filled with wants, play a crucial role in brain development. To quote a specific study, rats were placed in either a nurturing environment, or a deprived environment, and it was shown that these rats turned out to have epigenetic differences and grew up to either be anxious (deprived) or calm rats (nurtured). The deprived rats also had a significantly higher stress response later in life. This study shows pretty clearly to me that wants definitely have the potential to allow for human flourishing. Who’s to say cultural institutions and churches don’t have as vast, or greater an impact on human flourishing than that of medical institutions?

Conclusion

While it is clear that procedures like the one listed in this case are costly, and the money used would no doubt have the potential to save more lives if allocated differently, I believe that if money is put into procedures like this now, there is more hope in the future for it to become a regular routine life-saving procedure. The reading mentioned that at a point in time the pacemaker was considered extravagant, and now it has improved the condition of millions of lives. Artificial heart transplants might currently seem extravagant, but if resources are allotted to it now it has the potential to become a regular procedure that saves many lives, but it will not have a future if it is never invested in. On top of that, I also believe that cultural institutions and “wants” carry almost as equal weight in improving our lives, and while I believe medical care investment should receive more weight, our “wants” should not be dismissed so quickly.

Works Cited

Thomas, John, Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2014. Print.

Powledge T (2011). “Behavioral epigenetics: How nurture shapes nature”. BioScience 61 (8): 588–592.

“Behavioral Epigenetics.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 22 Feb. 2015.

Pictures

http://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/epigenetics/rats/images/Pup.jpg

http://www.papworthhospital.nhs.uk/docs/images/our_services/transplant/Total_Artificial_Heart_and_Human_Heart.jpg

I have to agree with you that what may be perceived as “embellishments” added to in the patients recovery may be expensive it was well worth it. But the question becomes, seeing as how the patient only lived a year was it worth it? The money could of been spent else where guaranteeing longevity in another case. So was the financial allocation the best decision? The other question I am prompted to ask is whether or not enough research was conducted to check the probability in which the patient would survive with longevity.

I agree with your stance on this issue. I believe that in order to gauge the effectiveness of the allocation of money for this specific treatment must be evaluated. Since only 50,000 individuals could possibly be affected by this extremely invasive and expensive treatment, in a strictly economic viewpoint, the funds used for essentially human research may have been better spent elsewhere. From an alternate viewpoint, how can one put a price on another’s life? If this man did not receive this artificial hear transplant, then his fate was determined. With the transplant, there was still a chance of lengthy survival.

Jonah, I agree with your question about the price of the life of a human being. This case discusses the appropriate allocation and distribution of financial resources. Alexi’s statement about the consequential effects for future live-saving procedures intrigues me, but the value of a human life strengthens the argument for the justification of the artificial heart transplant and special accommodations more. As previously discussed in this course, human lives possess a high moral status, which resulted in the principles of nonmaleficence and beneficence. Therefore, not performing the operation would not only violate the aforementioned principles, but it would also “put a price” on a status seen as invaluable.

I think the question that you posed ” would that money (used for the artificial heart procedure) be better allocated elsewhere, where the needs of the many would outweigh the needs of the few?” is an interesting one. Taking it a step further, why then, should we not focus solely on public health which benefits the population instead of medicine which benefits the individual? Wouldn’t it benefit more people? But what if it was one of your relatives in need of an artificial heart? By the same logic, shouldn’t we divide the money it would take to undergo the procedure and feed hundreds of children overseas? Questions surrounding allocation of resources has been brought up in multiple case studies that we have been assigned recently. For example, Steven, who required constant medical attention from the health care workers, was portrayed as being a heavy drain on resources. Since his condition was not improving, the question was brought up whether the resources that he required for upkeep would be better when provided to someone who had better prospects. Then there was Amelda, who, despite numerous attempts to force feed, was not gaining weight and was “taking up space” in the psychiatric unit, space that could be occupied by someone who actually was willing to receive treatment. But is the life of an individual with greater prospects worth more than the life of an individual who is declining? These are questions for further exploration.

Great post Alexi. Definitely one of the more interesting topics/discussions that could be proposed. I agree with Amy that the decision to allocate the money towards the investment in the heart transplant is favorable, as you stated that an investment might lead to the procedure being a regular choice in the future. It would also go against the principles of nonmaleficence and beneficence in choosing the cultural investments for the “wants”, but it does not put the later out of consideration.