Background

There are many ethical problems posed in the case regarding Henrietta Lacks. Unfortunately, her case occurred during a time where black individuals did not have the same rights as white individuals. This discrimination lead to black patients being treated only under the condition that it was then appropriate for medical research to be conducted on them. The two ethical issues I will tackle in this blog are should patients give consent to having their cells researched? Furthermore, to what extent should we violate autonomy to advance science?

Dilemma

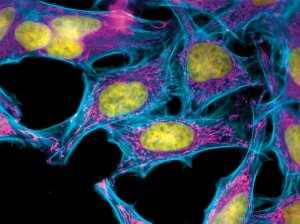

Lack’s cells were special as they were the first successfully grown human cells. Her cells led to many advances in the scientific community such as leading to the eradication of polio, a disease that plagued many. When Lack’s tumor cells were taken after her death from cervical cancer, “no one asked her permission to take the cells” (p. 254). However, the case did state “it was considered fair for medical researchers to conduct research on patients because they were being treated free of charge” (p. 254). Operating under this principle, which I believe violates autonomy of black individuals, I will evaluate whether the principle of autonomy was violating regarding Lack’s cell collection. It is clear that the racism at the time was unethical for a multitude of reasons and the case does not make it clear whether Lacks was aware that by receiving medical attention free of charge she was giving herself to research. If she was unaware of the extent to which research would occur on her, than this would violate the principle of autonomy because she did not give consent to the researchers. I believe that it is easy to agree that patients should consent to any research that might be conducted on them as without consent autonomy is violated.

However, if upon entering the hospital Lacks was informed that they would treat her only under the circumstance that her cells would be used for research later, than I do not believe her autonomy was violated past the violation of autonomy as a result of racism. Beauchamp and Childress state, “nothing about economically disadvantaged persons justifies their exclusion, as a group, from participation in research, just as it does not follow from their status as disadvantaged that they should be excluded from any legal activity” (p. 268). Since Lacks was financially disadvantaged, one could argue that she is being exploited by receiving medical attention from this hospital. However, if one were to continue down this path then in an attempt to “eliminate the problem of unjust exploitation” society would have to “deprive these individuals of the freedom to chose [to engage in research]” which “would often be harmful to their financial interests” (p. 268).

Reflection

One of the conditions of the principle of justice is allocation of resources. Allocation of resources implies that if “there is not enough to go around, [then] some fair means of allocating scarce resources must be determined” (principle of bioethics online website). What if we could make the resource less scarce? Then issues surrounding justice and prioritizing distribution would be less of a concern. In Lack’s case researchers utilized her cells after her death, and advanced science exponentially as her cells were the first “ever successfully grown human cells in a lab” (p. 254). In regard to organs, after individuals are deceased and are not organ donors, their organs decay, providing no advancements or cures for live individuals suffering medical conditions. Does it seem logical to allow all the organs or people who are not organ donors to go to waste after death? Should we as a society utilize the bodies of not only donors, but also individuals who are not labeled donors after their death for the advancement of science? Many would argue strongly against this, expressing concern that this blatantly violates the person’s autonomy and free will. However, currently arguable greater ethical violations are occurring due to the lack of available organs. Individuals might contemplate having another child for the primary purpose of providing one of their current children an organ necessary to live. Is this a greater violation of autonomy than taking the organs of someone who has lived a full life and now has died? The person who is dead would be unaware their autonomy is being violated unlike the child who will later realize that their autonomy was violated from a young age. In Lack’s case, her cells were taken after her death. Looking back, knowing all the amazing advancements that occurred as a result of her cells, it is difficult to imagine where we would be today without her cells. Nobel prizes, the treatment of polio, and cell culture industries all resulted from Lack’s cells. It is fascinating to imagine the advancement that could result from having access to organs after individuals are deceased. An average of 21 people die a day waiting for an organ transplant (http://www.organdonor.gov/about/data.html), it is interesting to think about how many lives we could save by implementing a policy regarding organ donation of the deceased. Furthermore, if we had an ample supply of organs, researchers would have more material to investigate and try treatments on, which could lead to eradications of other diseases and conditions. Although this notion seems far fetched, I think it is an interesting idea to consider in the light of Lack’s case. While Lacks was alive she was provided with medical attention and treatment she would not have received without the possibility of research on her cells after her death. If Lacks gave consent to the researchers allowing them to conduct research on her after her death, even though there is the concern of exploitation, I do not feel it was wrong to utilize her cell’s after her death. The main moral issue I found with this case was the lack of acknowledgement and compensation her family received after the success of her cells. The case states, “Henrietta’s family remain[ed] in poverty and have never received any benefit or recognition for their mother or grandmother’s contribution to science” (p. 254).

Work Cited

“African American Trailblazers in Virginia History.” N.p., n.d. Web.

Thomas, John E., Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. “Case 7.3: Who Owns the Research? The Case of the HeLa Cells.” Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. N.p.: n.p., n.d. 254-55. Print.

Principles of Bioethics. Thomas R. McCormick, D.Min., Senior Lecturer Emeritus, Dept. Bioethics and Humanities, School of Medicine, University of Washington, n.d. Web. <https://depts.washington.edu/bioethx/tools/princpl.html>.

Alexandra,

I think you bring up some interesting points in evaluating the role of autonomy and justice in the case of Henrietta Lacks. While I agree that racism was unquestionably a factor in healthcare at the time, I cannot deny that various other factors, such as socioeconomic status, were also at stake. It may have been common practice for researchers to conduct research on patients being treated free of charge, but this seems manipulative and exploitive. Whether Henrietta was informed of this practice and gave consent is irrelevant if she was manipulated in consenting via seeking out inexpensive care. Even if she was aware and informed, her autonomy could be compromised since she is financially unstable and faced with limited treatment options. I do not agree that it is moral, according to notions of justice, for the scientific community to advance as a result of a patient’s death. This brings to mind ideas that autonomy is irrelevant as long as society will benefit in the aftermath. Why act according to the patient’s wishes, assuming their wishes are in accordance with their best interest, while they are alive if their views are meaningless when they die? I think it is challenging to draw a comparison between living organ donation of minors and the donation of cadaveric organs without consent. Even though society may benefit from the consented donation of organs and cells, I argue that autonomy should be upheld. If an opt-out system were implemented, such knowledge of a system must be readily exposed and accessed.

I think it’s really interesting that you bring up the fact that autonomy of a dead individual is not the same as the autonomy of an alive individual because the dead person doesn’t know that their autonomy is being violated. While I do agree that it seems unethical to have the organs and cells of those who have died go to waste when their medical benefits could save the lives of many others, I do not think it is right to dismiss the autonomy of those who have died and use their tissues for science if it was not their will when they were living. If we begin to take this utilitarian view of justice too far, it won’t just be the dead that we take advantage of, the living could also begin to have their rights violated to benefit the health of others. On that note, I believe what happened to Henrietta Lacks was a clear violation of autonomy and took advantage of her socio-economic condition. While her cells have had enormous health benefits, it’s not like these advances couldn’t have happened if we got permission from somebody else to use their cells for science. However, I do agree that it would be beneficial to the overall health of individuals if we implemented an opt-out system of tissue donation, as long as it would be easy to opt-out and the components of the system were easily and fully understood by everyone. I would have to agree with the conversation we had in class that if an opt-out system were in place that most people would willingly donate tissues. The main reason people don’t donate now is the difficulties and inconvenience that come with opting in.

Alyssa,

It was interesting hearing your response to my discussion about organ donation after death. Although I agree with you that it does not seem “right to dismiss the autonomy of those who have died,” I am uncertain what “right” dead individuals have. Regarding the moral principle of autonomy, the individual must be competent and knowledgeable in the situation for their consent to be of weight. For individuals who have deceased, they are not competent and thus surrogate care-givers could be responsible for their decision. I think my argument could be adjusted to state if an individual is deceased it is up to the surrogate care-givers to make the decision about the patients organs. I feel this would be most similar to the way we handle cases of individuals who are in a vegetative state but still alive. However, this is not how we treat organ-donation cases. Whether the organs are to be donated is determined by the individual when they are alive. However, I think this system slightly overlooks the lack of knowledge the individual has on death. How is one to consent to a procedure when they die, if they have not experiencing death? Are they truly informed on what it will be like to be dead and their lack of need for their organs? Although these questions are extremely difficult to answer, they arise when discussing blood transfusions for Jehovah witnesses. An individual may consent to not getting a blood transfusion when they are healthy, but then when they are near death they may express interest in receiving the transfusion. What should be done? Is the individual more informed in the later situation as to what death is than the prior situation and thus able to give a more informed consent? Here is a situation, where we can act on the change of interest if we think it is ethical and save the person’s life with the blood transfusion. The same cannot be said about organs currently, since when the individual dies there is no way for them to communicate a change of desires and the wish to donate their organs. You begin to hint at a slippery slope stating, “it won’t just be the dead that we take advantage of, the living could also begin to have their rights violated to benefit the health of others”. Although this could be a possibility as there is always the possibility of situations being taking one step too far, I think this is a fallacy as I do not see how this event will inevitably follow from utilizing organs of dead individuals.

Michelle,

I think you bring up some interesting points regarding exploitation. I do think you raise a good point by explaining “even if she was aware and informed, her autonomy could be compromised since she is financially unstable and faced with limited treatment options”. As we discussed in class, financial need could place an individual in a position that leads to exploitation. Beauchamp and Childress state, “the problem of exploitation centers on whether solicited person are situationally disadvantaged and lack viable alternatives, feel forced or compelled to accept attractive offers that they otherwise would not accept”(p. 269). Henrietta Lacks would fall into this category of disadvantaged individuals who lack viable alternatives. However, if she consented without coercion of the medical faculty at the hospital, I do believe there are arguments that this action is not exploiting her more than say accepting minimum wage would. In terms of accepting minimum wage, individuals who are financially disadvantaged would arguably be exploited here also because people who have a greater financial status would not accept that income. I find it difficult to understand where the line is drawn regarding exploitation for individuals who are financially disadvantaged. Furthermore, an extreme standpoint might comment that any action a financially disadvantage person engages in could be the result of exploitation. Beauchamp and Childress state, “among the few readily available sources of money for some economically distressed persons are jobs such as day labor that expire them to more risk and generate less money that the payments generated by participating in phase 1 clinical trials” (p 270). Although this statement is not directly applicable to the Henrietta Lacks case because she was not getting paid, I think this comment can be expanded to her case. Denying Henrietta Lacks the opportunity to be treated free of charge in fear of exploitation would leave Henrietta Lacks no medical attention at the time, a scenario arguably more unfortunate than culturing her cells after her death. This being said, I do agree that her family should be given credit and should receive compensation for the advancements her cells have provided the world.