Background: Dr. Arman Asadour is a physician working in South Sudan for a vertical aid cholera treatment program funded by an NGO. His workstation has a mandate to only treat cholera patients and send those with other conditions to the local hospital. The local hospital is overflowing with patients and some patients arriving at the station have conditions treatable with NGO resources. Dr. Asadour is caught in two moral dilemmas in which he must decide whether to balance beneficence and justice. Treating non-cholera patients might cause an overflow of sick patients demanding NGO care, depleting resources that could be used to eliminate cholera. Admitting non-cholera patients for treatment might expose them to cholera patients at the facility. Overall, there the ethical question of whether the vertical treatment structure is the most effective way to improve the population’s overall health (Thomas, Waluchow and Gedge 267). The primary moral dilemma is whether to treat outside the mandate, and the secondary dilemma is whether he should ethically participate in the program at all.

Discussion: Dr. Asadour’s professional emphasizes beneficence, which provides the foundation for his uneasiness about selectively treating. He is facing an epidemic of cholera, but also an endemic presence of other diseases. It is a pandemic comprised of numerous illnesses. Brody and Avery provide evidence of why Asadour feels a strong duty to treat in such circumstances based on the ideas of social solidarity and vulnerable populations. Brody and Avery make a convincing argument that solidarity between fellow health care professionals and the larger lay community provides the basis for doctors’ duty to treat (44); they also argue that “a critical test of true social solidarity is whether we are willing to put the needs of vulnerable, underserved populations first” (45). When health systems neglect vulnerable populations it can result in mistrust of health officials by said populations, leaving them resistant to public health guidelines and therefore at risk for mortality (Brody and Avery 46).

No doubt this argument has to do with Dr. Asadour’s moral conflict over his station’s mandate. He is clearly invested in vulnerable populations because he chose to leave home country and work in an unstable, war-torn region. Employment with NGOs often pays less than other employment like private practice and many NGO physicians are volunteers and receive no payment at all. It would be frustrating for an individual who wants to generally serve the needy, to be hindered by a restrictive mandate. According to the case description, “Dr. Asadour wonders whether vertical aid programs simply undermine efforts by local authorities to develop sustainable health responses for their own communities and for health broadly,” (Thomas, Waluchow, and Gedge 267). This interplays with Brody and Avery’s argument of mistrust above. Clinics like Asadour’s may disrupt the normal flow of services in the area and establish a new norm for care delivery. If this new norm is one where only certain patients receive care while others are left to die while waiting for treatment at the overcrowded hospital, then it could result in community bitterness and frustration. These emotions may remain when Asadour’s NGO leaves, leaving the general community generally mistrustful of biomedicine. Mistrust of biomedicine could lead to continued spread of communicable diseases if patients refuse to seek treatment at local hospitals.

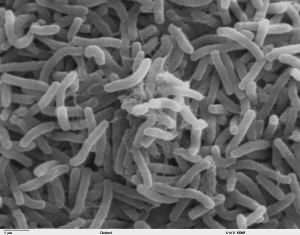

In context of justice, there are several aspects to consider that are in conflict with Dr. Asadour’s desire to treat non-cholera patients. The primary issue is how to allocate the NGO’s resources. While the NGO may have resources the hospital doesn’t, they were specifically provided to treat cholera and are limited in their own right. Cholera is a highly communicable disease spread by contaminated food and water. Death results from diarrhea-induced dehydration. Treatment involves intravenous fluids with electrolytes and antibiotics (WebMD). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the NGO workstation did not provide medical supplies for the treatment of viral conditions, chronic conditions, etc. If Dr. Asadour were to treat outside the mandate, he would likely still have to reject patients based on the supplies provided. When allocating scarce resources to equally needy individuals, one must also consider the prospect of success of treatment (Beauchamp and Childress 289). For example, if a patient reaches treatment before severe dehydration occurs, survival of cholera is highly likely. In the case of other diseases such as malnutrition, chronic diseases, etc., Dr. Asadour’s supplies might be used for the dual purpose of providing relief, but they will not be able to cure. His treatments are specifically effective in treating cholera.

Examining the vertical aid structure of Dr. Asadour’s organization from a broader perspective beyond individual patients reveals that its treatment plan may be futile. Hunt’s article “Cholera and Nothing More” examines ethical considerations of humanitarian aid programs addressing the disease. He says, “An important question to ask is what steps are possible to contribute to developing local capacity for preventing and addressing future outbreaks and building up infrastructure,” (56). Prevention and public health efforts are as necessary as treatment to prevent spread. In cholera’s case, improved water and food sanitation coupled with rehydration and antibiotics would eliminate the current epidemic and prevent another one from occurring in the future. However, the vertical aid structure employed by Dr. Asadour’s does not provide any provision for improvement in the community’s infrastructure or sanitation education programs for refugees. In this way the agency is doing little to stop the propagation of the disease, but is their work unethical?

Regardless of intentions, the NGO is providing care with scarce resources and limited funding to some individuals and that, in itself, is an act of beneficence. I believe Dr. Asadour should continue to treat according to the mandate if he wants to make the most impact with his resources available. In other words, I would recommend taking utilitarian approach to treatment. However, the program’s structure may not be the most just or fair way to utilize aid funding. However, I don’t think this makes the organization’s action unethical. Only if the NGO’s work were to leave the area worse off than when it arrived or cause the failure of local healthcare delivery after its departure (i.e. the mistrust of the community or the disruption of local hospitals’ ability to treat) would I view it as and unethical organization.

Works Cited

Brody, Howard, and Eric N. Avery. “Medicine’s Duty to Treat Pandemic Illness: Solidarity and Vulnerability.” Hastings Center Report 39.1 (2009): 40-48. Web. 19 Apr. 2015.

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. “Justice.” Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. 249-301. Print.

“Cholera: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention.” WebMD. WebMD, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

Hunt, M. R. “‘Cholera and Nothing More'” Public Health Ethics 3.1 (2010): 55-59. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

Thomas, John E., Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. “Case 8.2 Ethics and Humanitarian Aid: Vertical Aid Programs.” Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2014. 267-68. Print.

Carolyn,

I agree with you completely that the cholera NGO should not extend a hand to provide aid to non-cholera conditions. Like you said, they may only have the resources to treat cholera and nothing else, and if they attempt to provide aid to more chronic and complex conditions, the cholera treatment team may end up doing more harm than good. Therefore, it is not the responsibility of Dr. Asadour and his chlorera treatment team to provide assistance to the local hospital. Instead, resources should be allocated more efficiently so that 1) cholera can be eliminated completely and 2) more funds can be allocated towards treating more complex diseases.

Although one may argue that as a physician, Dr. Asadour’s duty is to provide care, I do not think he should provide care if he does not have the resources to do so. Dr. Asadour may find himself attempting to treat patients and then midway realize that he does not have what he needs to treat them, which may cause further harm to the patient than any real benefit.

You raise several interesting in points in your post. I agree with you that Dr. Asadour and the organization’s decision to pursue a vertical aid program to combat cholera epidemic is not unethical. When working with an epidemic of a highly communicable disease that is causing high mortality, it becomes logistically reasonable and ethical to have this kind of mandate. By having a mandate to focus on cholera, the organization is most likely going to be able to treat a large amount of people in a shorter amount of time than if they had a horizontal type of program. Also, by not treating cholera, the organization increases the chances that other people will get it which will ,in the long-run, only constrain the limited resources available even more. A vertical program to treat cholera can stop the epidemic which then will gradually divert resources back to other illnesses. However, I do agree with you that there does need to be some sort of investment in the infrastructure and prevention programs in order to ensure another cholera outbreak does not happen again in the future. By implementing an effective prevention/sanitation programs, then we decrease the likelihood of having another vertical program and having to turn away other patients. If these programs can be implemented successfully, then the organization’s action becomes even more justifiable. Overall, the organization is not being unethical because they are trying to help the largest amount of people in the shortest amount of time. Ideally, every individual would have access to medical care regardless of their condition; however, the reality is that that is not possible with the resources available.

Carolyn –

This was a very good analysis of an unfortunately common dilemma faced in the medical field. I wholeheartedly agree that given that the supplies was delivered for the treatment and control of cholera, it should be used only in the treatment of the aforementioned ailment. The issue here is the fact that the ethical complexities associated with doing so are difficult to ignore. Every medical professional takes on oath where they solemnly swear they will treat every patient they come across, stabilize them to the best of their ability, and no cause them any harm. Although the guidelines for the usage of the supplies was specified, there is an unjust burden placed upon any medical personnel that must literally turn a patient away, being fully capable of treating their illness. Therefore, although I agree with the guidelines which state that patients not afflicted with cholera are to be turned away, I believe measures should be put in place to lessen the burden of this or even to allocate resources for those in need of different care.

Dr. Asadour’s discomfort arises from being exposed to non-Cholera patients who seek out care he should, technically, not provide since he is working within a vertical aid mandate. As a highly educated person, of course he would still be aware of the wide need for his medical expertise in the surrounding area regardless of if these patients physically came to him or not. However, the burden of turning away a patient at his door is greater than the burden of his awareness of need. The duty to rescue, as discussed by Beuchamps and Childress, involves discussion of the relationship between a person X and person Y(202). If person X is Dr. Asadour, then person Y is the patient directly in front of him who needs care. This is true regardless of whether or not the patient has cholera or not. Also, as long as Dr. Asadour does have the appropriate supplies for that patient and will not come to harm, he is obligated to treat the patient. It seems to me that the only way to prevent this situation would be to remove the possibility of a non-Cholera person Y. Thus, perhaps Dr. Asadour’s cholera clinic should be set up within a larger hospital setting. Thus, an initial physician would screen all patients and only the ones with cholera would be sent to Dr. Asadour. Of course, this idea requires adequate resources and funding. In the end however, beneficence dictates that Dr. Asadour treat whomever is in need of treatment if that patient is physically in his clinic. The only way to prevent this situation, which would divert resources and time from the mandated Cholera victims, would be to ensure that non-cholera patients do not become a person Y through proximity to Dr. Asadour.

Carolyn, you bring up many good points. I would like to comment on the ethical/unethical nature of vertical aid structures. For this case with Dr. Asadour, the NGO he is working with is specifically treating cholera. However, as you mentioned, they are not doing anything in order to prevent the disease or subdue the epidemic. As a result, they are pouring resources into a problem that will continue until proper sanitation measures are put in place. In addition, the side effects of the efforts cause a slew of negative side effects (based on the logic you employed in your argument), including mistrust of health officials in the general public. Therefore, though, the NGO no doubt has good intentions, their plan of action is not equipped to be able to help South Sudan improve their current status and therefore, they are doing more harm than good, which is not an act of beneficence and is unethical.