Research Involving Alzheimer Patients and Moral Status

The Question:

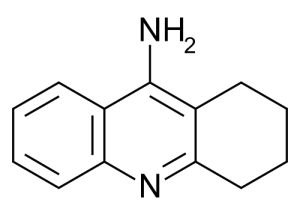

There is a new drug called Tetrahydroaminoacridine (THA) to be tested on Alzheimer’s patients which could possibly reduce Alzheimer’s disease. Dr. Selleck, who was running the trials, contacted Ann Wilson, the director of St. Mary’s, in order to recruit elderly patients. The guidelines for testing the patients would be that both the patient and their closest relative provided written consent. If the patient was unable to make a decision, then their only consent would be provided by their closest relative. Ann was strongly opposed to this study as she said “I will simply not permit elderly patients under my care to be used as guinea pigs” (Thomas, Waluchow, and Gedge 116). Now the question presents itself of what an individual would do if he/she was in the position to make that decision.

Discussion:

Though there are many arguments and discussions about the case, one of the primary arguments made by Ann was that elderly Alzheimer’s patients are an especially vulnerable group who should not be used in medical experiments. Now with this in mind, a question of moral status arises. What constitutes the elderly deserving of special consideration and protection? And would Ann’s decision making be different if this wasn’t Alzheimer’s affecting the elderly but rather another disease affecting another age of patients?

Five main theories of moral status are discussed by Beauchamp and Childress and what stands out to me the most is the theory based on cognition. This theory implies that the more cognitively vulnerable individual tends to have a lower moral status. This could be seen in the case of experimenting on rats versus experimenting on humans, as rats have a lower cognitive ability and thus a lower moral status. In the case of Alzheimer’s, the brain shrinks as a result of nerve cell death and tissue loss. According to the NCBI, areas of the brain shrink dramatically and lesions occur that could impair cognitive ability to that lower than some monkeys.

So where do Alzheimer’s patients stand relative to other patients in terms of moral status? Are some patients valued below that of nonhuman primates? Therefore, an argument for the testing of Alzheimer’s patients could be made by devaluing their moral status. On the contrary, Ann’s argument to have the Alzheimer’s patients relieved of testing shows that she morally values elderly Alzheimer’s patients and thus ranks them high in terms of their relative moral status.

Though cognitive ability is an interesting thought, this dilemma cannot be sole attributed to that theory of moral status alone. There are other theories involved, as well as many other factors aside from moral status. In addition, I analyzed just a very small part of such a large case presented. The arguments both for and against are infinite and very complex.

Works Cited:

Colbert, Treacy. “What Does Alzheimer’s Do to the Brain?” Healthline. Healthline, 20 Sept. 2016. Web. 19 Jan. 2017.

Gold, Carl A, and Andrew E Budson. “Memory Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Development of Therapeutics.” Expert review of neurotherapeutics 8.12 (2008): 1879–1891. PMC. Web. 18 Jan. 2017.

Thomas, John E., and Wilfrid J. Waluchow. Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics. Peterborough: Broadview, 1987. Print.

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

James,

I think you make a very good argument here and I like how you chose to focus on the cognitive ability of the patients rather than the age, as I see this as a much better argument approach. Your approach to the topic via cognitive vulnerability makes some very good factual points about how the brain of an Alzheimer patients is impaired and in turn gives them the cognitive ability that may be even below a monkey. While all the points you make related to this topic are factual and valid, have you considered how these facts also strengthen the argument to allow the experimentation?

Federally, we have protocols, laws, and regulations that allow scientists and doctors to conduct animal research as well as human research. With this in mind, would these patients not be perfect for this new experimental drug if they are to consent? Similar to how people chose to be organ donors for the greater good of other people, if these patients want to be a part of the study with the hopes of helping other people once they pass, why should we stop them? In the unfortunate cases where young children pass away, it is up to their parents to decide if they want to donate their child’s organs to other people in need and possibly save a life of a stranger in need. On that same track, if we compare the cognitive abilities of a young child to that of a middle staged Alzheimer’s patient, then it is perfectly acceptable for a close relative to make the decision of participation or not on behalf of said patient.

I would say not even giving the patients the opportunity to consider participating in the study is a) depriving them of their autonomy and b) not allowing them to possibly fulfill a meaningful purpose; which is incredibly unfair considering they are grown adults and are being treated like children who can’t have a cookie before dinner. As discussed in the case, many elderly feel as though they are burden to society and allowing them to partake in a study such as this is something that could really help them feel a higher purpose and receive a sense of accomplishment for helping others. In a world where many of these patients cannot live without the assistance of a nurse or caretaker, this may be their only way to receive independence and freedom.

Works Cited:

“Animals in Science/Research: Laws and Regulations.” New England Anti-Vivisection Society, 2017. http://www.neavs.org/research/laws

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Thomas, John E, et al. “Case 3.1: Research Involving Alzheimer’s Patients.” Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics, Broadview P, 1987.

Hey Shelby,

You bring up a very great point with “consent” and this concept of a sort of sacrifice in the hopes of helping other people. I definitely see where you are coming from and I support your analysis of the situation. I do realize that you are speaking on behalf of the Alzheimer’s patients and I am sure that you have realized that the decision itself is not based solely on the Alzheimer’s patients but rather a very complex concept.

Ann herself experiences this divide between her own moral values and decision making and the values and decision making of the elderly Alzheimer’s patients. She ultimately, has major power in this decision for this case especially. So a counter argument for not allowing the elderly patients to be tested would present itself.

Many arguments can be made in favor of Ann’s decision. The moral principle of “non-maleficence” plays a major part in the gap between Ann’s decision of rejecting the experimentation and the overall consensus of Alzheimer’s patients in the study. Ann values non-maleficence when she said that she does not want her patients to be treated like lab rats. Therefore, she wants her patients to not be “harmed” by any extraneous factors. Her supposed empathy and caring of the patients along with her power of director of St. Mary’s Hospital leads her to the decision that she has made and thus the ultimate conclusion for the case. Then the question comes up of how does non-maleficence play in terms of individual autonomy? Is it justified that one’s non-maleficence can trump another individual’s self-autonomy?

Works Cited:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Thomas, John E, et al. “Case 3.1: Research Involving Alzheimer’s Patients.” Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics, Broadview P, 1987.

Hi James,

I think you addressed the moral dillemma in a rather thoughtful manner. I think your point regarding the patient’s vulnerability is rather interesting and insightful. I believe that some patients need special consideration due to their impaired cognitive ability. If the patients are granted this additional consideration, then this population will consequently lack the ability to consent to the study. Therefore, can and should the experiment be conducted at all within this population? I think it is rather problematic to group the whole population as vulnerable, as patient’s in the early stages of the disease might have some ability to reason. I think that a very specific criteria may be necessary to determine the patients that require additional moral consideration within this population.

Here’s another point to consider: although we lack information concerning the potential benefits of the study, would it be ethical to violate the patient’s moral status if the study benefitted future Alzheimer’s patients? From a utilitarian perspective, it would be ethically sound to conduct the experiment if the study brought about a greatest advantage for a greater number of people.