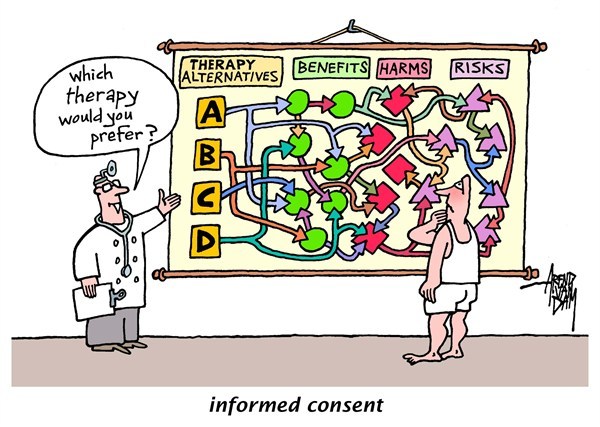

Beauchamp and Childress outline four main principles of healthcare ethics: respect for autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice. In my opinion, no other issue blends these principles together as well as the requirement of informed consent in medical research. Informed consent is a vital component of the trust between a healthcare professional and a patient. If a patient is not given all the information regarding a medical treatment, that trust becomes void. The US Congress defines informed consent as

“including information about the nature of the experimental procedure, the reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts, the benefits to the subjects or others, alternatives, the extent of the confidentiality of the records, possible compensation for injuries, the obligation to contact subjects if problems arise, and the right of subjects to refuse to participate or to withdraw.” (Brody & Engelhard 288)

It seems that voluntary consent should be of utmost importance when practicing ethical healthcare. However, this has not been the norm in all forms of research. One of the most appalling of these instances occurred during World War II, when the Nazi regime funded medical experiments performed on subjects who were not given the right to withdraw or refuse to participate. These experiments were implemented without the consent of the participants, in conditions so inhumane they led to the death and suffering of hundreds of innocents. One of the doctors responsible for these atrocities justified his actions by stating that his research prevented the endangerment of innumerable human beings. He emphasized that those deaths were not in vain because they led to medical breakthroughs that helped a great number of people.

It seems that voluntary consent should be of utmost importance when practicing ethical healthcare. However, this has not been the norm in all forms of research. One of the most appalling of these instances occurred during World War II, when the Nazi regime funded medical experiments performed on subjects who were not given the right to withdraw or refuse to participate. These experiments were implemented without the consent of the participants, in conditions so inhumane they led to the death and suffering of hundreds of innocents. One of the doctors responsible for these atrocities justified his actions by stating that his research prevented the endangerment of innumerable human beings. He emphasized that those deaths were not in vain because they led to medical breakthroughs that helped a great number of people.

The case concerning the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital involved researchers who neglected to inform patients of their participation in an experiment where they were injected with cancerous cells. Instead, the patients were told they were “receiving a skin test for immunity or response” (Coppenger 106). Despite this course of action, the experiment led to valuable results in the field of cancer research. Withholding information from participants is a violation of their right to consent. Subjects cannot agree to participate when they are not aware of the true parameters of a study. Taking cases like this into account, the question remains: is it morally justifiable to disavow informed consent when the results of an investigation could lead to a “greater good”?

This is a problematic situation from a moral and ethical standpoint. On one hand, the autonomy of a patient is compromised due to their inability to consent to an experiment or a procedure. On the other hand, successful research could prove to save or improve the lives of countless individuals. Whether the ends justify the means is an age-old question. I believe the sovereignty and safety of patients should not be compromised under any circumstances. Some researchers argue that denying consent is ethical when evaluating specific cases. I disagree with this opinion. If we apply a spectrum of ethical excuses debating the morality of the right to consent, where do we draw the line? At which point do we deem it acceptable to sacrifice the lives of the few to save the lives of the many? That line of thinking produced the Nazi ideology that allowed for dozens of experiments performed on unwilling victims. The essential respect for autonomy should not be granted for some and denied for others. “Informed consent is a fundamental principle of health care.” (Cordasco 1)

Works Cited

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Brody, Baruch A., and H. Tristram Engelhardt. “Consent of Adults to Experimentation.” Bioethics: Readings & Cases. Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1987. 286-90. Print.

Coppenger, Mark T. “Hyman vs. Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital.” Bioethics: A Casebook. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1985. 105-06. Print.

Cordasco, Kristina M. “Obtaining Informed Consent From Patients: Brief Update Review.” Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices.U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 27 Jan. 2017.

Hi Gisell! I really enjoyed your post. It is very thoughtful and the pictures are a great addition! You pose the question of whether it is morally right to bypass informed consent in search of a “greater good.” For cases such as the Nazi experiments or the Tuskegee study (check it out!), I agree that these are morally wrong. They went too far by violating the patient’s right to informed consent and by forcing them to participate in harmful and even deathly experimentation.

However, I see a key difference between the blatantly unethical experiments of World War II and this case at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital. I currently conduct cancer research and know that, despite the common misconception, injecting the cancer cells of another person should not negatively affect a *healthy* patient. Cancer, unlike other illnesses, is not contagious (Palmer, 2011). In fact, there have been studies similar to the posed experiment and none of the patients developed cancer because their body’s immune system fought it (Palmer, 2011). It is when you infect an immunodeficient individual when it becomes dangerous. As a result, this study –compared to those of the Nazis — does not present an inherent danger to the patient. Sure, it is scary to hear that cancer cells are going into your body; however, if the patient is properly informed of its mechanism of action, their fear should be reduced.

This brings me to my next point. While I think that this case is different in its threat to harming the patient, I still agree that the patient should be informed. In the two cases mentioned by Palmer, both physicians faced legal repercussions for failing to properly inform the patient of the procedure — even though the patient did not develop cancer. Informing the patient presents an initial challenge for the doctor, as most patients would not consent due to fear of the disease. However, I think losing a few fearful but informed participants in the study is not as bad as moving forward with the experiment while leaving them in the dark. Disregarding informed consent breaks the trust between patient and physician.

REFERENCES

CDC. (2016). U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. CDC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

Palmer, B. (2011). Can you give someone cancer? Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/explainer/2011/12/hugo_chavez_suggested_the_united_states_gave_him_cancer_is_that_even_possible_.html

Gisell,

This was a very interesting post! We talked a lot about informed consent in class today and I really like the approach you took to addressing this issue; it was an idea that I wish I would have brought up in class today.

I think two of the most important and relevant cases that we discuss related to this topic are “Case 10.3: Should Patients be Informed of Remote Risks of Procedures” and “Hyman vs. Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital”. While these cases individually have different dilemmas (one is about a medical related death and the other about a human experimentation lawsuit), once we strip away the finite details of the cases, they are actually incredibly similar. Essentially, we are asked to decide whether or not a patient/experimental subject, both having a procedure performed voluntarily and at their own free will, needs to be informed about some seemingly minuscule aspect of their upcoming procedure that has a less than 0.1% chance of causing bodily harm.

When I first read about “Case 10.3: Should Patients be Informed of Remote Risks of Procedures”, I thought that the patient should absolutely have been informed of the very small health risk that could ensue from his procedure, but after reading the “Hyman vs. Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital” case, I have actually changed my decision. As I previously discussed, these two cases are basically addressing the same issue. I realized, though, after taking a look at both of them that I really don’t believe there is a need to inform patients/experimental subjects about all minutes, essentially harmless details. In the latter case for example, the study ended up finding that healthy patients do produce an immune response to cancer cells places directly under the skin. This outcome would have likely never been found if the researchers had originally informed their subjects of the fact that they were injected them with cancer cells. As someone who is actively involved in animal research, I strongly believe that research is a very important process for scientific advancements and that if you are not going to cause any harm to a patient by not disclosing all information at hand, then you are doing no harm.

By fully informing all patients/subjects about a threat that is basically not there, as a physician or researcher you run the risk of said person rejecting a procedure or experiment; which can often be detrimental to a person’s health/scientific advances. While I’m sure the vast majority of people would prefer to be informed of these details, I do not believe that it is absolutely necessary unless a person’s life is directly in danger.

Works Cited:

Barton-Hanson, Jem, and Renu Barton-Hanson. “Causation in Medical Litigation and the Failure to Warn of Inherent Risks.” British Journal of Medical PractitionersA834 8.4 (2015): n. pag. Print.

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Coppenger, Mark T. “Hyman vs. Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital.” Bioethics: A Casebook. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1985. 105-06. Print.

Thomas, John E, et al. “Case 10.3: Should Patients be Informed of Remote Risks of Procedures?” Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics, Broadview P, 1987

Hi Gisell,

I enjoyed this discussion! You make a great connection to the case concerning the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital. What constitutes an adequate disclosure of information to patients is certainly controversial, and this is relevant to the anesthesia case as well.

I agree that voluntary consent should be of utmost importance when practicing ethical healthcare, and I’d like to add that disclosure should include information about the nature of the procedure, its risks, its alternatives (including no treatment), and its expected benefits. Over winter break I had an endoscopy and colonoscopy, and I remember that the gastrointestinal doctor and anesthesiologist both informed me of the risks of the procedures: bleeding from the site of the biopsy, a perforation in the colon, or an adverse reaction to the sedative used. At the time, this information actually reduced my anxiety because I was informed that such results were extremely unlikely to occur; signing the forms after being fully informed about the procedures encouraged me to be actively involved in my own care.

Moreover, I would be upset if I was a research participant uninformed of the cancerous nature of the cells. The researchers are nonetheless obligated to inform the participants of this aspect of the procedure and its risks (if any): the cells are cancerous cells, but they do not cause cancer. Hence, for the choice to be fully autonomous, patients must be informed truthfully about what is involved, if only because consent is more than assent–more than the patient’s giving into the physician’s wishes or doing what is expected. When a research participant authorizes the physician or researcher to treat him, he does not merely say yes, but autonomously and knowledgably decides and assumes responsibility for the decision (Vaughn 203).

Vaughn, Lewis. Bioethics: Principles, Issues, and Cases, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. Print.