In Principles of Biomedical Ethics, Beauchamp and Childress present a hypothetical situation in which a psychiatrist “informs all patients that he may not keep information confidential if serious threats to other persons are disclosed” (Beauchamp and Childress, 208). After “learning of his patient’s intention to kill an identified woman… the psychiatrist may now either remain aloof or take measures to protect the woman by notifying her or the police, or both” (Beauchamp and Childress, 208). What does the principle of beneficence demand of the psychiatrist in this situation?

In my opinion, the psychiatrist should contact the woman, the police, or both in an effort to protect the woman’s life. While the psychiatrist is under no obligation to act in this situation, the principles of positive beneficence overrides all opposing arguments. The “principle of beneficence refers to a statement of moral obligation to act for the benefit of others” (Beauchamp and Childress, 203). Conveniently, in this case the best interests of the patient and the woman are the same. By preventing the patient from causing any harm to the woman, the psychiatrist is acting in the best interest of the woman by saving her life, and the patient by preventing him from committing an act he will later regret.

Beneficence “is optional rather than obligatory;” however, there are some situations in which an individual is highly encouraged to act (Beauchamp and Childress, 205). One of the principles of positive beneficence, which holds an individual accountable in a situation, is the duty to “prevent harm from occurring to others” (Beauchamp and Childress, 204). In this situation, the psychiatrist is responsible to prevent the harm that could potentially be caused to the woman and the harm that would be imposed on the patient if he followed through on his wish to kill the woman. An additional principle is the duty to “rescue persons in danger” (Beauchamp and Childress, 204). The woman in this situation is obviously in severe danger of being hurt, or killed, and as a result, the psychiatrist is under an obligation to circumvent the threat. The patient is also in danger of being imprisoned, most likely for the rest of his life. In terms of these principles, the psychiatrist is expected to act in this situation to protect the woman and the patient’s future.

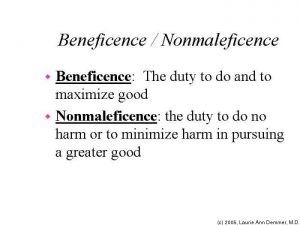

“One of the most common ethical dilemmas arises in the balancing of beneficence and nonmaleficence” (“Beneficence vs. Nonmaleficence”). However, in this hypothetical situation, the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence complement one another. If the two principles conflict with one another, like in Dax Cowart’s case, then you must decide which carries more weight in the situation and should be respected over the other principle. The principle of nonmaleficence means “to do no harm” (“Beneficence vs. Nonmaleficence”). By telling the woman, the police, or both, the psychiatrist is preventing any harm from occurring to the woman or possible harm to the patient that could arise as a consequence of his actions. In addition, the psychiatrist is obeying the principles of beneficence by taking actions that “help prevent or remove harms or to simply improve the situation of others” (“Beneficence vs. Nonmaleficence”).

Taking everything into consideration, while the psychiatrist is under no obligation to act in this situation, due to the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, he should inform the woman, police, or both. The psychiatrist will suffer no risk or inconvenience by acting in this case. In addition, he is obligated to prevent harm and act in the best interest of the individuals involved.

Works Cited:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

“Beneficence vs. Nonmaleficence.” Beneficence vs. Nonmaleficence. University of California Regents, School of Medicine, 2008. Web. 12 Mar. 2017.

I appreciated that you touched on the comparison between beneficence and nonmaleficence, as well as the fact that disclosing the patient’s intent to kill another human being poses no risk to the psychiatrist whatsoever. While researching, I found that the American Psychological Association has approved some instances where it is considered ethical for psychiatrists to break confidentiality, such as in child abuse cases, mental health cases, or instances where someone’s life is in danger. I believe that establishing a Code of Ethics for psychiatrists is important, because it sets the framework for when cases should be reported to the authorities, as well as help to protect psychiatrists from potential lawsuits. By doing so, psychiatrists now have an obligation in some situations to do what is just.

Citation:

Goleman, Daniel. “What You Reveal To a Psychotherapist May Go Further.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 13 Apr. 1993. Web. 12 Mar. 2017.