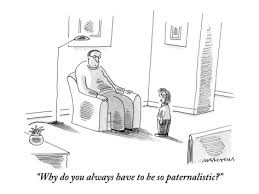

The concept of paternalism in biomedical ethics gives authority of people’s bodies and autonomy to qualified persons, and could lead to a serious abuse of power if used as reasoning for simply controlling patients or their families’ choices for a host of reasons. As controversial and as it is, paternalism is needed in cases where it is truly in the patient’s best interests to forgo their wishes, but there will always be a gray area in determining what those interests are.

The concept of paternalism in biomedical ethics gives authority of people’s bodies and autonomy to qualified persons, and could lead to a serious abuse of power if used as reasoning for simply controlling patients or their families’ choices for a host of reasons. As controversial and as it is, paternalism is needed in cases where it is truly in the patient’s best interests to forgo their wishes, but there will always be a gray area in determining what those interests are.

Intervention in suicide attempts are, necessarily, considered paternalistic. In “Confronting Death: Who Chooses, Who Controls?”, Dax Cowart asserts that “The right to control your own body is a right you’re born with, not something that you have to ask anyone else for […].” This commonly upheld idea of autonomy is the precise reason the principle of paternalism exists – to essentially ignore a person’s autonomy if the reason for doing so benefits the person in question. Paternalism regarding cases of suicide, however, involve the act of suicide as a moral right and the state of the person attempting it. Psychiatrists often consider a suicide attempt as a sign of a mentally incompetent person, but in doing so they are singling out the act of suicide as justification for revoking a person’s autonomy. If suicide is a “human right”, how is it different than any other action a person does to change his or her life for the better or worse? A way to approach this dilemma is the relativity of suicide to other tasks, momentarily ignoring the social stigma surrounding it. People with suicidal thoughts should of course be given options, assistance, and concern, but doctors do not necessarily have inherent authority to intervene in a suicide attempt when not asked or given consent (this source explains various philosophical principles of thought on this topic).

Since the aforementioned texts define suicide along the lines of a human right, should society approach physician-assisted suicide any differently? To some, it is considered acceptable to assist in somebody’s suicide based on the argument that it is more humane if the person will accept no other alternative. To do this, though, would be to classify suicide as an acceptable, maybe even untouchable, act under the terms of autonomy and a person’s right to his or her own body.

From these conclusions, there is an evident correlation between intervention in suicide and physician-assisted suicide. If intervening in a suicide attempt on terms of beneficence, even if a person is mentally competent, is considered morally acceptable, then physician-assisted suicide is ethically justifiable under similar criteria of beneficence. There must be much more discussion surrounding the relation of suicide intervention and physician-assisted suicide, as each of those topics pertains to restricting autonomy and the ever-growing presence of paternalism in society.

Sources:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2009, 2013. Print.

Cowart, Dax, and Robert Burt. “Confronting Death: Who Chooses, Who Controls?” The Hastings Center 28.1 (1998): 14-24. JSTOR. Web. 12 Mar. 2017. <http://www.jstor.org.proxy.library.emory.edu/stable/3527969>.

Kelly, Chris, and Eric Dale. “Ethical Perspectives on Suicide and Suicide Prevention.” Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 01 May 2011. Web. 12 Mar. 2017. <http://apt.rcpsych.org/content/17/3/214>.

Image Credit:

http://sociologylegacy.pbworks.com/w/page/75297230/Paternalistic

Elisabeth,

This was a really thought provoking post that made a lot of good connections with things we have previously discussed. Paternalism in theory is a good concept in order to save people’s lives but like any ethical principle, it has its flaws. To the naked eye, any principle that will save a person seems like a great idea until you break it down and realize the other autonomous rights that are violated in this situation. Informed consent is a principle that isn’t even considered when we skip straight to paternalism and override all of a patient’s rights and abilities to make decisions. In the context of what you discussed between physician assisted suicide and self-inflicted suicide, informed consent still plays a vital role. If a person wants to commit suicide, they consented to themselves that that is what they want carried out. This is no different than a patient giving consent or even explicitly asking for physician assisted suicide to be carried out. The weary part of both of these situations is the chosen wording, as you began to mention when you talked about the stigma surrounding suicide. Trigger words like suicide sent most people into a panic to try to help someone and we almost immediately consider said person to mental incompetent. But who is to say that he/she is actually of a sound state of mind and came to an ethical conclusion that this is what was best for him/her? I think you make some very good points about how if a person can knowingly decide they want to end their life at their own hands, then why can’t they decide to end their life at the hands of a certified physician?

In a simpler form, say a person has accidentally cut themselves while trying to cook dinner. You have two options- go to the emergency room and receive stiches or suture the wound yourself because you think you can handle it. In either case, you are reaching the same end result of healing your wound, but there are two paths to get there. In cases when a person wants to end their life, whether they do it themselves or with physician assistance, they are reaching the same end result. Therefore, there should be no difference in the stigmas and rules (if you can call them that) about whether a person can commit suicide or go about it with assistance. This is the main flaw in paternalism. While saving a life may always seem like a good thing, a competent person should be allowed to make their own decisions regarding their life without forced intervention from an outside source.

Works Cited:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2009, 2013. Print.

Cowart, Dax, and Robert Burt. “Confronting Death: Who Chooses, Who Controls?” The Hastings Center 28.1 (1998): 14-24. JSTOR.

Shelby, I’m curious–why did you choose to compare a wound from what I assume is a kitchen knife to that of suicide which involves someone’s life/aliveness?

Thank you, Elisabeth, for sharing your thoughts. To say suicide is a “human-right” feels a bit severe. I would suggest, instead, posing it with less provoking language, such as, “people have a right to die.” Framing it in the context of death—a fixed event in all human lives—feels more natural and is less likely to put people in “defense mode” where most would instinctively conclude, “killing oneself is bad.” That being said, applying the principle of paternalism to situations regarding suicidal ideations and/or attempts is an interesting notion. My question to your mini-dissertation within this blogpost is: does motive or intent behind suicide attempt change how you would apply the concept of paternalism? If so, what and why? With consideration from our class discussion today on nonmaleficence, beneficence, and moral responsibility and your claim of an “ever-growing presence of paternalism is society,” I ask: does this paternalism extend to strangers or does it only apply to person(s) or groups we have associations with?

Pamela,

Thanks for commenting! I don’t think that the personal motive or intent behind suicide changes how the concept of paternalism would be applied unless someone’s autonomy was clearly compromised through coercion, misunderstanding, influence, or non-voluntary medical decisions. Reasons for ending one’s own life, so long as they are completely autonomous, are personal and confidential. I understand when you say that the language regarding suicide as a “human right” is strong, but that’s exactly what it is — control over one’s body for personal and confidential reasons. In this sense, I stand by the language used if there is no violation of autonomy or compromising factors surrounding the decision of suicide.

In regards to your second question, the point of paternalism is that it extends to strangers to promote looking out for what is best for people when they may not be able to do so. This doesn’t mean that you can knock a cigarette out of somebody’s hand on the basis that it isn’t good for them — they are making a conscious choice to smoke — but you could comment on the unhealthy nature of cigarettes and contribute to their informed decision, as well as designate areas where it is appropriate to smoke if applicable (such as in consideration to the discussion we had in class about Emory’s tobacco-free campus). Paternalism in response to strangers (not involving doctor-patient relationships, but just citizen to citizen) inherently contains a different set of guidelines to the extent that your beliefs do not hardbody else. Designated smoking areas and designated smoking zones are justified in this sense that they act in the interests of the common good and prevent exposure to second-hand smoke while simply regulating an action some may choose to perform to certain areas. What are your thoughts on paternalism in society, particularly pertaining to the example of Emory’s paternalistic tobacco-free campus policy? Is it justified?

Thanks!

Elisabeth Crusey

Elisabeth,

Your blog post was very thought-provoking! I love how you draw a connection between suicide intervention and physician-assisted suicide. I feel like there is a glaring difference between Physician-assisted suicide and suicide intervention that may explain why people are so inclined to prevent suicide: time. Most of the time, when people attempt suicide, it occurs outside of the hospital scene. Those who discover the suicide attempt have no idea how competent the patient is and therefore have a moral obligation to intervene. When it does occur at hospitals, typically, it occurs in psychiatric units where patients have already been declared incompetent and thus require treatment. In PAS, there is enough conversation and time to solidify whether or not a patient is competent enough to make this decision and determine that this pathway is the one that benefits the patient the most.

Additionally, there is a grey area when patients are declared competent whether or not doctors should indeed let them commit suicide/engage in PAS. What would be defined as beneficence and who decides it? When there is a conflict between the patient and the doctor on what benefits the patient, I think the doctor should be more inclined to side with the patient when the patient is competent.