This article challenges the claim that “access to [universal] health care is necessary to ensure health, which is necessary to provide equal opportunity” (Sreenivasan 21). The author doesn’t claim that universal healthcare or equal opportunity are unimportant, but rather that equal opportunity doesn’t necessarily result from universal healthcare access.

It is hard to deny that ensuring better health allows people to accomplish more, which could be seen as providing them with more opportunities. Furthermore, providing healthcare seems like a perfectly logical way of ensuring health. However, the author explains that the core of this argument relies on defining opportunity, and specifically what everyone’s equal share of opportunities is. This is where the argument falls apart; not everyone starts with the same share of opportunities. Rather, the shares of opportunity that can be maintained, restored, or increased with better healthcare are actually better defined as “relative shares” (23). Healthcare facilitates better health, which in turn facilitates a maintenance of opportunities, but those opportunities are not equal by nature.

The purpose of this argument is not to discredit any benefits of universal healthcare, but rather sets the author up to make the next argument: using the same amount of money to ensure more socioeconomic equality actually has a bigger benefit on health and overall opportunity than just spending it on healthcare. In the author’s words, “A society does more to move its citizens toward their fair share of health when it devotes the equivalent of the health care budget to improving the social determinants of health than when it runs a national health care system. It follows that equal opportunity does not require universal access to health care” (27).

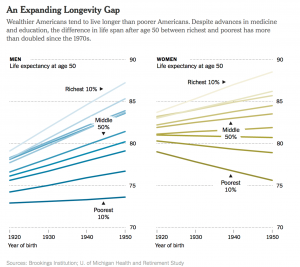

I appreciate the fact that the author is not completely discrediting the role of universal healthcare. Rather, it addresses only a small portion of the overall problems created by the current socioeconomic gradient. As the paper acknowledges, and as I have discussed and read about in health and sociology classes, socioeconomic status is one of the most important factors in determining health outcomes, including disease rates and mortality rates. The following is an example of expected lifespan at age 50 in the mid-1900s based on individuals’ income brackets. Income inequality has only increased since then.

While, in theory, it sounds nice to spend money on fixing the problem of income inequality, accomplishing that is extremely difficult. There is no easy way of distributing the money or identifying who needs it the most.

The immediate implementation of some of these ideas may not be possible, but it is still important to acknowledge the fundamental causes of uneven distribution of health and unequal access to opportunities. It’s also important to acknowledge the flaws in arguments for and against important issues like universal access to healthcare. This article also does a good job of exposing many of those flaws. It is imperative, however, to ensure that healthcare benefits don’t get cut just because the motives for universal healthcare or certain treatments are flawed—they still play an important and beneficial role.

Sreenivasan, Gopal. “Health Care and Equality of Opportunity.” Hastings Center Report 37.2 (2007): 21-31. Web.

Hi Jack!

I really enjoyed your blog post! You did a really great job of outlining the author’s arguments and providing evidence that socioeconomic status is one of the main drivers in health status. Although the graph you posted in your blog as well as the graphs in the article indicates that even with the presence of universal healthcare, lower socioeconomic status individuals have worse health outcomes, I am hesitant to believe that some form of universal healthcare is unnecessary. Even if universal healthcare or an easier access to healthcare among the lower statuses does not completely dissolve the discrepancy between health outcomes in the upper and lower classes, is that enough reason to not provide the lower classes with access to healthcare? A discrepancy may still exist among the classes, but I don’t think that the way to resolve this is to just eliminate or make healthcare access to the lower classes harder to obtain.

As you referenced in your post, there are definitely flaws when it comes to universal healthcare, just as there are consequences with not providing a form of universal healthcare or some sort of opportunity equalizer. One way to combat these issues could be to have more specific policies for certain diseases or health issues as we partly touched on in class today. We referenced a hypothetical case in which a woman’s husband is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and she may have to give up their house in order to cover the costs of his treatments because their income fell just above the line where they had to cover the costs on their own. Specifically for a progressive degenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s, where there is no cure and 95% of cases are sporadic/ have no known causes, treatment is necessary for the rest of a patient’s life and can be very expensive (“Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia”). Not only would a patient need to pay for treatments that may not work, they may also need to pay for a full-time caregiver if the patient doesn’t have a family member with the physical ability to take care of him or her. In addition, since the primary risk factor is age, it is not as if the disease is preventable or caused by poor lifestyle choices on behalf of the individual. Although it may be difficult to decide which diseases/conditions should qualify, I think that creating a policy in which certain diseases qualify to receive full or a large portion of coverage regardless of socioeconomic status may be an option. Obviously this type of policy comes with its own flaws as well, but a combination of this type of policy as well as some form of universal healthcare may be able to help close the gap in health outcomes among the different classes.

References:

“Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia.” Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Association, 2017. Web. 10 Apr. 2017.