Henrietta Lacks has gone to space, won several Nobel prizes, and fueled the multibillion-dollar cell culture industry but she doesn’t know any of this. She hasn’t received accolades or been compensated with a single cent either. How? Because she died of cervical cancer in 1951 at John Hopkins Hospital. Shortly after her death, a biopsy of her tumor was taken for research in a cervical cancer lab but instead of dying like cells had before, her cells reproduced another generation every 24 hours. The cells were shared with other researchers before being mass produced and used to test the first vaccine for polio that ended up extinguishing the disease for good. Permission for doctors to use anyone’s cells or body tissue at that time was normally not obtained so the fact that Henrietta or her family didn’t give direct consent is not surprising.

The part that is unsettling is that even after the 1970’s, when informed consent came into practice, nothing was done to compensate her family. However, I do think it’s important to note that George Gey, the original scientist who worked with the HeLa line, attempted to protect the privacy of the deceased and made the cells available to all interested in biological research at no cost. Biotechnology laboratories and academic research institutions are the ones who continually divided her cells and profited millions while the Lacks family couldn’t afford proper healthcare, not the scientists attempting to cure cervical cancer. Although I don’t believe it’s just to use a person’s remains without their consent, at the time, common practices were followed. The real injustice is that over 50 years later, rich white profit-seeking men are continually exploiting a poor African American woman who lost her battle with cancer.

A somewhat similar but more modern case was presented in 1990 with the case of Moore vs. Regents of California. John Moore had visited the University of California Medical Center in 1976 seeking leukemia from Dr. David Golde. Dr. Golde took cell samples and created a cell-line without the knowledge or consent of Mr. Moore. Moore, a well-educated white man, sued for a portion of profits gained from his own body upon finding out that Dr. Golde was attempting to sell the line to Genetics Institute, a biotechnology corporation in the commercial application field. The Court did not agree with Mr. Moore as they concluded that bio-medical research would be undermined if individual patients had the power of profit from medical advancement as a result of their own physical make-up. It said nothing about the implications of profit on the researchers side. This decision made a blanket statement that says medical researchers have the ultimate right to body tissues of patients for private gain.

The issue boils down to Henrietta’s autonomy versus the principle of benevolence in reference to the lives that were saved with research involving cell research. The obvious benefit is the obliteration of polio and the lives and resources saved in doing so. However, does this benefit to society justify violating a patient’s autonomy? I do think the benefits to advancement in the medical research field are significant but I don’t believe that justifies exploiting a patient for profit. Dr. Gey’s collection method isn’t ethically sound in our eyes but when the cells were taken, common practice was followed. Does that make him excused from the controversy on grounds that his intentions were pure? Or should he still be held accountable for all the implications that followed? Lastly, how does Moore vs. Regents of California affect future patient rights? I look forward to hearing what you all think about the controversy!

Resources:

Moore v. Regents of the University of California. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/property/property-law-keyed-to-cribbet/non-traditional-objects-and-classifications-of-property/moore-v-regents-of-the-university-of-california-2/

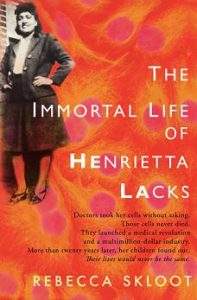

Skloot, Rebecca, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Random House, 2010)

Hi,

I enjoyed reading your blog post and think you touched upon some important points. Specifically, I liked your inclusion of the Moore vs. Regents of California case and how you explained that even in a case where the subject whose cells were being researched was alive, he still did not get any compensation for his involvement. With this in mind, connecting to the concept of justice as we have been discussing in class, I think it is important to remember the egalitarian part of justice and how all subjects of research should be treated equally. Though I do not agree with researching Henrietta Lacks’ cells without her family’s consent, I do agree that they should not have been compensated on the basis of egalitarian justice as a public policy. If Henrietta Lacks’ family was compensated then in order to uphold egalitarian justice within public policy, everyone who ever participated in medical research by random chance through blood donations, organ donations, or anything else, would also have to be compensated. This idea of compensation is unrealistic and in a sense becomes unethical since “research participants are coerced when an offer of payment…gets them to participate when they otherwise would not” (EurekAlert). Thus, in order to ensure that all research participants are being treated fairly and are entirely in agreement with the research being done, it is best that monetary compensation is left out of the equation.

Work Cited:

EurekAlert! The Global Source for Science News. https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2012-02/thc-prv022212.php

Hi Laura,

Thank you for reading and replying to my post! Although I do agree that all research participants should be treated fairly, I don’t think that means monetary (or alternative) compensation should be left out of the equation. Also, there should be few instances of “participating in medical research bu random chance” as all researchers are required to attain the consent of their participants. The IRB does not consider compensation to research participants as a benefit of research, rather, it’s to offset the time and inconvenience of participation. There are no federal guidelines pertaining to compensation but both researchers and the IRB make sure that subjects are provided full information and in turn give consent that is free of coercion or influence. It is important to acknowledge that excessive or inappropriate compensation is problematic because it can tempt subjects to participate against their judgement, lie or withhold information that would make them ineligible to participate, and can create coercive situations when a third party is involved. But eve after considering issues with excessive compensation, there’s still an argument for fair compensation of all participants. You brought up blood donation as an example where a participant is not compensated but I argue that at a Red Cross sponsored blood drive you give blood and in return receive supervised care for a short time after the procedure, free food and drinks, coupons or gift certificates for restaurants/stores/services, a goodie bag, and sometimes are entered in a lottery for a grand prize. When compensation takes the form of a drawing or lottery system, patients participate knowing that they will most likely receive nothing. As long as the prize would be considered fair compensation if split among the number of participants, it quiets the issue of coercion. We should aim to ensure that all research participants are being treated fairly, yes, but also compensated fairly, even through non-monetary avenues.

Sources:

http://www.irb.vt.edu/pages/compensation.htm

Hi,

I enjoyed reading your post and appreciate the way in which you related the HeLa case to “Moore v. The Regents of University of California” (1990). I was interested by the information that you presented and decided to research the case:

Procedural History:

The Supreme Court of California holds that there is a requirement for the disclosure of physicians’ research interest, but there are no property-related claims.

Although I find this to be more of a legal question than an ethical one: can there be a property right claim to bodily fluids and tissues that have been removed from the body?

Holding/Rule:

“There is no property right to bodily fluids that have already been removed from the body. Moore’s complaint states a cause of action for breach of fiduciary duty or lack of informed consent, but not conversion” (“Moore v. The Regents of University of California”).

Reasoning:

The court discussed the disclosure issue and decided that the doctor was required to disclose the research interests. On the conversion issue, Moore argues that he continued to own his cells following their removal from his body, at least for the purpose of directing their use.

Can Moore and Lacks still “own” their cells when they are removed from their bodies?

Works Cited

“Moore v. The Regents of University of California.” One L. Briefs. 2009. Web. 11 April 2017.