In this reading, the authors start off by discussing how different countries deal with healthcare, and ultimately ask to what extent, and at what cost ought a society to provide equal healthcare for all.

Healthcare in America accounts for around 18% of the total GDP, comparatively lying around 7% for the United Kingdom. On top of that, it was also discussed in this reading that while over 95% of the UK’s population has access to health care (99% in Germany), only 90% of US citizens have that same access. In regards to portion of GDP and percentage of the population accounted for, the score currently sits at 2-0, and it is not in America’s favor. However, while it is a widely accepted fact that the United States is still lagging in terms of Healthcare when compared to Europe, this does not necessarily mean that us American’s are losing on all fronts.

A piece of evidence presented that elaborates on why Europe is not “all that” is the example regarding how the United Kingdom went about balancing costs and healthcare. While the United Kingdom may spend less on healthcare than the United States or Germany, it comes at the cost of quality of care, and the UK essentially reduced these costs by “erecting barriers” to their citizens in regards to higher technology treatment. Not only that, but patients are often discouraged from certain “high cost or higher technology interventions” that clearly would provide the patient with greater benefits. So why does America pay so much for healthcare? Simply put, it is because America wants to provide their citizens with the opportunity for the best healthcare possible. While there are less people who have access to these opportunities when compared to the United Kingdom, those that do have more doors open to them. Unfortunately the comparison between the two is not black and white, and the question now is whether or not it is ethical for the United States to turn their back on 8-11% of Americans in the hopes of providing the majority with better, and higher quality healthcare.

While I believe that every person should have the right to healthcare, I feel that the benefit outweighs the costs when said benefit is better all around healthcare. The United States relatively speaking provides a slightly lower number of people with a high level of healthcare, and I feel that that triumphs over providing a slightly higher number of people with lower quality health care.

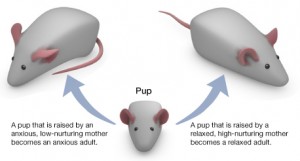

Also I would like to mention a common counterargument that can be made to support the superiority of healthcare in Europe (or rather the inferiority of American healthcare) in that American’s are not healthier, and do not live longer than Europeans. Even this statement, while statistically supported, cannot truly determine the quality of American or European healthcare systems because that point relies on the assumption that healthcare is the only determinant of a person’s health. In reality healthcare provides a long list of benefits for any person that qualifies, but the health of an individual at the end of the day is heavily reliant on genetics, diet, violence, and the list goes on. That being said, healthcare can only do so much, and ultimately there are a lot of health determinants that are well outside anyone’s control.

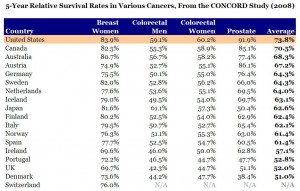

Below is an image which further proves my point that American offers a higher level of health care treatment

Below is another statistical analysis that shows that there are many different determinants of health that are not reliant on healthcare

Works Cited:

Brody and T. Engelhard, “Access to Health Care,” Bioethics: Readings and Cases

http://b-i.forbesimg.com/theapothecary/files/2013/11/CONCORD-table12.jpg (image1)

http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/full-width/images/2012/04/blogs/graphic-detail/20120428_WOC086.png (image 2)