Background: Dr. Arman Asadour is a physician working in South Sudan for a vertical aid cholera treatment program funded by an NGO. His workstation has a mandate to only treat cholera patients and send those with other conditions to the local hospital. The local hospital is overflowing with patients and some patients arriving at the station have conditions treatable with NGO resources. Dr. Asadour is caught in two moral dilemmas in which he must decide whether to balance beneficence and justice. Treating non-cholera patients might cause an overflow of sick patients demanding NGO care, depleting resources that could be used to eliminate cholera. Admitting non-cholera patients for treatment might expose them to cholera patients at the facility. Overall, there the ethical question of whether the vertical treatment structure is the most effective way to improve the population’s overall health (Thomas, Waluchow and Gedge 267). The primary moral dilemma is whether to treat outside the mandate, and the secondary dilemma is whether he should ethically participate in the program at all.

Discussion: Dr. Asadour’s professional emphasizes beneficence, which provides the foundation for his uneasiness about selectively treating. He is facing an epidemic of cholera, but also an endemic presence of other diseases. It is a pandemic comprised of numerous illnesses. Brody and Avery provide evidence of why Asadour feels a strong duty to treat in such circumstances based on the ideas of social solidarity and vulnerable populations. Brody and Avery make a convincing argument that solidarity between fellow health care professionals and the larger lay community provides the basis for doctors’ duty to treat (44); they also argue that “a critical test of true social solidarity is whether we are willing to put the needs of vulnerable, underserved populations first” (45). When health systems neglect vulnerable populations it can result in mistrust of health officials by said populations, leaving them resistant to public health guidelines and therefore at risk for mortality (Brody and Avery 46).

No doubt this argument has to do with Dr. Asadour’s moral conflict over his station’s mandate. He is clearly invested in vulnerable populations because he chose to leave home country and work in an unstable, war-torn region. Employment with NGOs often pays less than other employment like private practice and many NGO physicians are volunteers and receive no payment at all. It would be frustrating for an individual who wants to generally serve the needy, to be hindered by a restrictive mandate. According to the case description, “Dr. Asadour wonders whether vertical aid programs simply undermine efforts by local authorities to develop sustainable health responses for their own communities and for health broadly,” (Thomas, Waluchow, and Gedge 267). This interplays with Brody and Avery’s argument of mistrust above. Clinics like Asadour’s may disrupt the normal flow of services in the area and establish a new norm for care delivery. If this new norm is one where only certain patients receive care while others are left to die while waiting for treatment at the overcrowded hospital, then it could result in community bitterness and frustration. These emotions may remain when Asadour’s NGO leaves, leaving the general community generally mistrustful of biomedicine. Mistrust of biomedicine could lead to continued spread of communicable diseases if patients refuse to seek treatment at local hospitals.

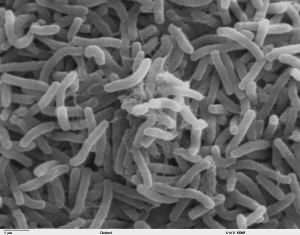

In context of justice, there are several aspects to consider that are in conflict with Dr. Asadour’s desire to treat non-cholera patients. The primary issue is how to allocate the NGO’s resources. While the NGO may have resources the hospital doesn’t, they were specifically provided to treat cholera and are limited in their own right. Cholera is a highly communicable disease spread by contaminated food and water. Death results from diarrhea-induced dehydration. Treatment involves intravenous fluids with electrolytes and antibiotics (WebMD). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the NGO workstation did not provide medical supplies for the treatment of viral conditions, chronic conditions, etc. If Dr. Asadour were to treat outside the mandate, he would likely still have to reject patients based on the supplies provided. When allocating scarce resources to equally needy individuals, one must also consider the prospect of success of treatment (Beauchamp and Childress 289). For example, if a patient reaches treatment before severe dehydration occurs, survival of cholera is highly likely. In the case of other diseases such as malnutrition, chronic diseases, etc., Dr. Asadour’s supplies might be used for the dual purpose of providing relief, but they will not be able to cure. His treatments are specifically effective in treating cholera.

Examining the vertical aid structure of Dr. Asadour’s organization from a broader perspective beyond individual patients reveals that its treatment plan may be futile. Hunt’s article “Cholera and Nothing More” examines ethical considerations of humanitarian aid programs addressing the disease. He says, “An important question to ask is what steps are possible to contribute to developing local capacity for preventing and addressing future outbreaks and building up infrastructure,” (56). Prevention and public health efforts are as necessary as treatment to prevent spread. In cholera’s case, improved water and food sanitation coupled with rehydration and antibiotics would eliminate the current epidemic and prevent another one from occurring in the future. However, the vertical aid structure employed by Dr. Asadour’s does not provide any provision for improvement in the community’s infrastructure or sanitation education programs for refugees. In this way the agency is doing little to stop the propagation of the disease, but is their work unethical?

Regardless of intentions, the NGO is providing care with scarce resources and limited funding to some individuals and that, in itself, is an act of beneficence. I believe Dr. Asadour should continue to treat according to the mandate if he wants to make the most impact with his resources available. In other words, I would recommend taking utilitarian approach to treatment. However, the program’s structure may not be the most just or fair way to utilize aid funding. However, I don’t think this makes the organization’s action unethical. Only if the NGO’s work were to leave the area worse off than when it arrived or cause the failure of local healthcare delivery after its departure (i.e. the mistrust of the community or the disruption of local hospitals’ ability to treat) would I view it as and unethical organization.

Works Cited

Brody, Howard, and Eric N. Avery. “Medicine’s Duty to Treat Pandemic Illness: Solidarity and Vulnerability.” Hastings Center Report 39.1 (2009): 40-48. Web. 19 Apr. 2015.

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. “Justice.” Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. 249-301. Print.

“Cholera: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention.” WebMD. WebMD, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

Hunt, M. R. “‘Cholera and Nothing More'” Public Health Ethics 3.1 (2010): 55-59. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

Thomas, John E., Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. “Case 8.2 Ethics and Humanitarian Aid: Vertical Aid Programs.” Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2014. 267-68. Print.