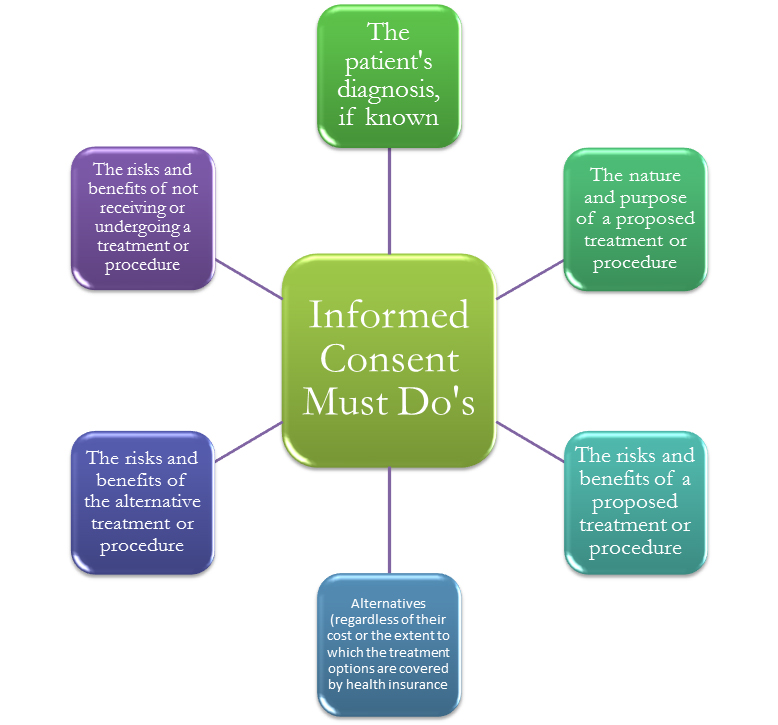

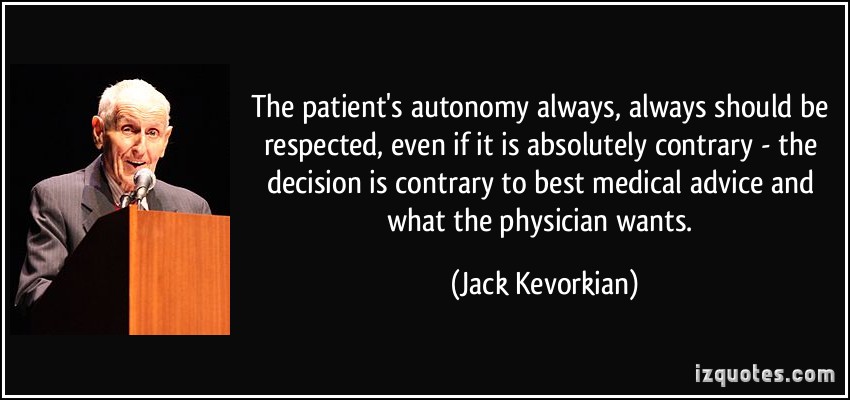

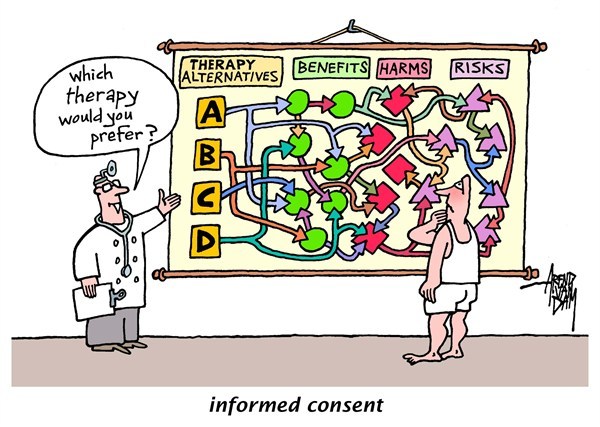

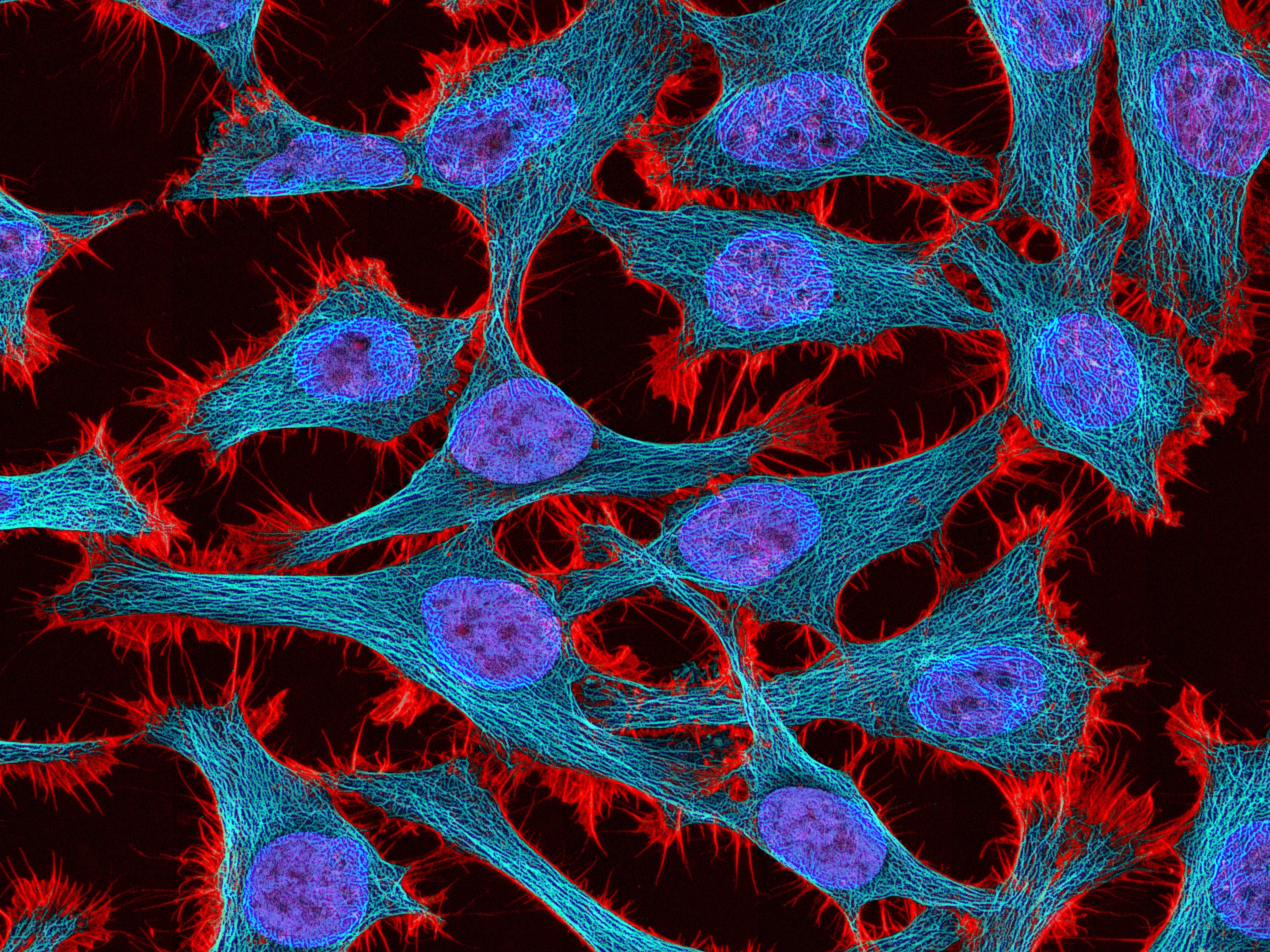

The case of the HeLa cells presents an interesting dichotomy between justice, fairness, and the greater good. The case highlights the tragic story of Henrietta Lacks, who died from cervical cancer at age 31 in 1951. A posthumous biopsy of her tumor was taken without the consent of Henrietta or her family members. This case represents one of the most egregious forms of medical misconduct, in which doctors neglected to receive informed consent. Informed consent is a necessary component of research or medicine whenever dealing with patients. Henrietta Lacks never consented to the biopsy or the redistribution of her cells. Her family was never compensated for the decades of research using Henrietta’s cells. “Currently, cells can be bought and sold without the patients’ permission, but tissue rights advocates suggest that these often-unwitting donors deserve a share in the profits their cells eventually reap.” (Devine) Cases like this highlight the importance of full informed consent. It is immoral for a doctor to perform a procedure on a patient without their knowledge, even posthumously. Without informed consent, patients do not have autonomy. The principle of respect for autonomy is one of the utmost important principles of bioethics. It is paramount to a successful doctor-patient relationship. Exceptions to this rule should only be considered in extraordinary cases, for instance, some “exceptions to full informed consent are: If the patient does not have decision-making capacity, when the patient has waived consent, and when a competent patient designates a trusted loved-one to make treatment decisions for him or her.” (De Bord)

Taking samples from a patient, such as biopsies, should always be discussed with either the patient himself or a family member. Moreover, the physician should ensure that the patient can provide full informed consent regarding the procedure and the use of the specimen. “The Patient Consent Form and associated Patient Information Sheet (necessary for most studies) should be written in concise and explicit language that anyone can easily understand, explaining clearly the need for the specimen, the overall objective of the research and why it is important (in lay terms).” (Geraghty et al.) This case is reminiscent of Dr. Richard Ward’s actions toward the Nuu-chah-nulth. The Nuu-chah-nulth case was discussed in class earlier in the semester. Dr. Ward took blood samples from members of the Nuu-chah-nulth and distributed it for the use of genetic studies without their consent.

Taking samples from a patient, such as biopsies, should always be discussed with either the patient himself or a family member. Moreover, the physician should ensure that the patient can provide full informed consent regarding the procedure and the use of the specimen. “The Patient Consent Form and associated Patient Information Sheet (necessary for most studies) should be written in concise and explicit language that anyone can easily understand, explaining clearly the need for the specimen, the overall objective of the research and why it is important (in lay terms).” (Geraghty et al.) This case is reminiscent of Dr. Richard Ward’s actions toward the Nuu-chah-nulth. The Nuu-chah-nulth case was discussed in class earlier in the semester. Dr. Ward took blood samples from members of the Nuu-chah-nulth and distributed it for the use of genetic studies without their consent.

However, another issue regarding Henrietta’s case is that her cells went on to aid in research that led to a vaccine for polio, among other scientific breakthroughs. Without these cells, there is no guarantee that these breakthroughs would’ve occurred. This is an issue of Henrietta’s autonomy versus the principle of benevolence regarding the countless patients helped with the resulting research. The question at hand is, does the fact that the cells have saved and improved countless lives make up for the way they were obtained? This is truly a difficult question to ponder because of the significance of the researched performed with HeLa cells. Personally, I do not think the benefit the cells have provided justifies the method through which they were obtained. The incredible violation of patient autonomy cannot be excused with any outcome. The doctor who took the initial biopsy did not realize the extent of their worth. He simply violated Henrietta’s right to consent to the procedure. I would love to hear more opinions in the comments. Do you believe these actions can never be excused? Do you agree with the idea that “uprooting contemporary ethical principles, like getting informed consent for research on tissues, and applying them to periods where they did not exist undermines our appreciation of the past in critical ways.” (Wilson), excusing the retired methods of tissue collection?

References

De Bord, Jessica. “Informed Consent.” Informed Consent: Ethical Topic in Medicine. University of Washington School of Medicine, 7 Mar. 2014. Web. 07 Apr. 2017.

Devine, Claire. “Tissue Rights and Ownership: Is a Cell Line a Research Tool or a Person?” Columbia Science and Technology Law Review. N.p., 09 Mar. 2010. Web. 07 Apr. 2017.

Geraghty, R. J., A. Capes-Davis, J. M. Davis, J. Downward, R. I. Freshney, I. Knezevic, R. Lovell-Badge, J. R W Masters, J. Meredith, G. N. Stacey, P. Thraves, and M. Vias. “Guidelines for the Use of Cell Lines in Biomedical Research.” British Journal of Cancer. Nature Publishing Group, 09 Sept. 2014. Web. 07 Apr. 2017.

Wilson, Duncan. “A Troubled Past? Reassessing Ethics in the History of Tissue Culture.” SpringerLink. Springer US, 04 Aug. 2015. Web. 08 Apr. 2017.