Or just no exploitation period.

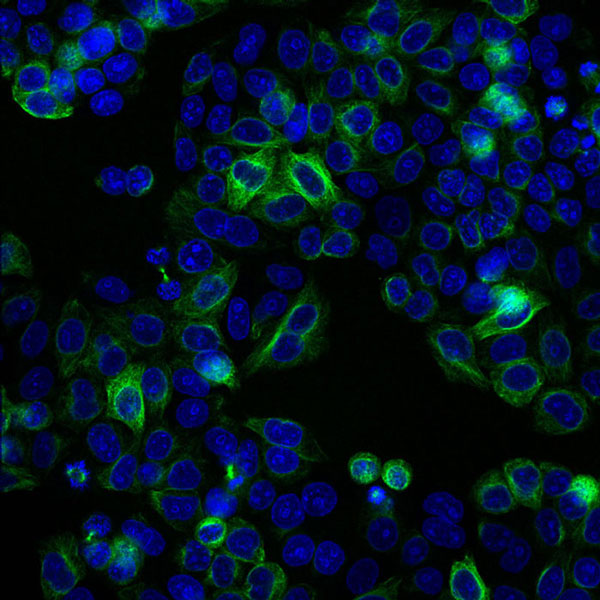

This week we read about the infamous case of Henrietta Lacks, a 31 year old cancer patient who upon passing away had her cells stolen from her without her consent or knowledge. In addition, her family was never informed that their beloved one’s cells were being used in research labs. Most importantly, after years of secretly conducting research on Henrietta’s cells, also known as HeLa cells, researchers have won numerous Nobel Peace Prizes and launched the multibillion dollar cell culture industry. Meanwhile, Henrietta Lacks family has never received any compensation for having their beloved ones cells exploited, nor have they seen a single cent of the profits earned from this research. No matter the amount of good things research on HeLa cells has done for the world, there is no excuse for why Henrietta’s family has not yet been compensation for this deception.

In the passage, “Vulnerability, Exploitation, and Discrimination in Research”, Beauchamp and Childress address three problems involved in enrolling the economically disadvantaged in research: 1) undue inducement, 2) undue profit, and 3) exploitation. Under inducements include monetary payments, shelter, and food and are considered unduly large and irresistible payments. In contrast, undue profits are when “subjects receive unfairly low payments, while the sponsor of the research gains more than is justified” (Beauchamp and Childress, 269). One could argue that it would be unethical for a researcher to approach a subject who is weak and constrained by their poverty, and thus more likely to be coerced into being a research subject with menial benefits. The compensation offered could be so little that it is viewed as exploitative. Contrastingly, monetary payments could be unduly large and irresistible and be seen as coercive or as a form of bribery. Therefore, after reading this passage from Beauchamp and Childress, I have concluded that there is no real solution for how one can determine a method of payment or reimbursement that is nonexploitative.

One simple solution could just be to not exploit subjects in the first place; the Lacks’ doctors could have just informed the Lacks family and received their consent. I think an even better solution would be to ask research subjects how they would like to be compensated. Obviously the subject would not be allowed to make an outrageous request like ask for $1 million dollars. For example, say a homeless person was recruited for research, if the person requested 1 meal and shelter for a night, the researchers should ablige their request. Better yet, for low income subjects, researchers should say, ” Even if you decide you will not do this study, we will still offer you shelter, food, money, etc. just for your time.” This would show the subjects that the researchers are sincere in their endeavors. But I think the best solution would be to allocate more money to fix entire low-income communities so that the issue being an “economically disadvantaged” person is resolved completely.

Ultimately, in the case of Henrietta Lacks’ family, where billions of dollars has been raised off of the research done on Lacks’ cells, there is no reason why Lacks’ family should still be poverty stricken with no access to healthcare themselves. It is unfortunate that no justice has been served, and I am curious to know why no legal action has been taken against this case. Even if Lacks’ family cannot afford to finance a lawyer, it is appalling that no one, not even the many researchers who have profited from this deception nor a generous lawyer willing to offer their time to the case have come forth to at least help Lacks’ family gain the compensation they deserve.

Works Cited

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. Print.

Thomas, John, Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2014. Print.