Determining how scare medical resources are distributed amongst a healthcare system is a vital question that must be addressed in order to ensure a hospital is operating at its full efficient. As the state of Oregon has shown, ranking the value of medical procedures subject to great scrutiny, as many will disagree on the specific of the methodologies used for the ranking. Rather than asses procedures on “importance,” healthcare systems should analyze their capacity to withstand demand shocks and develop a system of patient triage that maximized positive health outcomes.

Patients who require organ transplants are likely aware of scarcity in healthcare, as there are a limited number of hospitals equipped to perform such surgeries. Also, there is a perpetual shortages of available organs, demonstrating how some components of medical care are already vastly outstripped by demand. Consequently, when the demand for a common medication or vaccine increases beyond predicted levels, the US healthcare system can increase the production of a desired compound and take emergency action to provide increased access to care.1 While scarcity will increase, scaling up production of common medications and vaccines demonstrates is an example of how a healthcare system can successfully deal with instances of shortage and avoid excessive rationing.

However, the availability of most medical care falls somewhere between these two examples. Additionally, more nuanced factors like age and ability to pay for treatment influence how the medical care is allocated. Setting aside these other factors, a purely utilitarian ethical model would promote treating patients who:

1. Require immediate care

2. Present a high chance of recovery.

That is, if two patients require immediate care, the patient more likely to have a positive health outcome (or have a lower associated cost relative to improvement) is prioritized. For sake of argument and simplicity, I’ll assume that these two conditions are independent of each other; though in reality, there is likely a direct relationship between how long a patient can wait to be treated and the chance of having a good medical outcome.

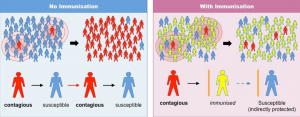

Though this may appear to be contradictory to the principle of justice, a healthcare system should focus on operating in a utilitarian manner to promote justice through efficiency and positive health outcomes. By prioritizing patients who are more likely to recover, aggregate-level utility (positive health outcome vs. negative health outcome) is maximized by the utilitarian triage system. Under this framework, patient justice is not secondary to the quantifiable medical outcomes, but rather an extension of the healthcare system operating at its greatest possible efficiency. Justice at the aggregate-level is not about selecting people who are “deserving” of medical care in a social sense, but rather ensuring that a hospital can cause as many good health outcomes as possible.2 In any healthcare system that does not operate efficiently, there will be patients who are untreated or under treated as a result of operation inefficiency. Consequently, hospitals can promote healthcare justice by reducing the number of patients who fall victim to an inefficient healthcare system.

1) Lorenzoni, G. 2006. Theory of Demand Shocks. National Bureau of Economic Research.

2) Gatter, RA; Moskop, JC. 1995. From Futility to Triage. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 20: 194.