Do you think it is acceptable for health professionals to decide which patient is more important to save based on QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years? Using this method the number of years an individual can live is favored over the number of lives that can be saved. “QALYs are calculated by estimating the years of life remaining for a patient following a particular care pathway and weighting each year with a quality of life score” (Beauchamp and Childress 239).

The article “QALYfing the value of life” gives the following example: “Andrew, Brian, Charles, Dorothy, Elizabeth, Fiona, and George all have zero life-expectancy without treatment, but with medical care all but George will get one year complete remission and George will get seven years’ remission” (Harris 118). Using QALYs, George would be treated over the other six patients since he has a longer remission than the other patients. By valuing life-years, QALYs may require the physicians to sacrifice six lives in order to save one. This situation exemplifies the tension that can form between QALYs and beneficence. QALYs instructs the physician to assist the patient with the highest QALY score, while they are also obligated to help all of the patients due to their duty to rescue and help. Using this example as a baseline of how QALYs would be implemented in health policy, I think that QALYs should not be implemented into the system because it is ageist, favors patients that require relatively cheap treatments, and does not make a distinction between life-saving and life-enhancing treatments.

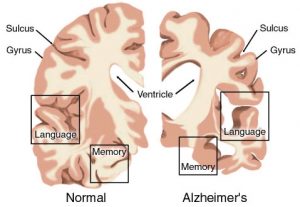

QALYs is ageist because younger individuals tend to have higher QALYs on average than older people. As a result, if there were ever a situation in which a physician had to choose to assist one of two patients, an older and a younger individual, the physician will always choose the younger patient. I believe that this is unethical and brings into question the issue of justice in bioethics. This method of valuing one’s life requires the disregard of the generalized assumption that every individual is considered equal, and no one person should be regarded as more important than another. By using QALY, physicians are obligated to prioritize younger patients over others, and thus consider those patients more important.

In addition to being ageist, this particular way of valuing one’s life also favors patients that require cheap treatments. Using this system, “the quality of life of those with illness or disability is ranked, on the QALY scale, below that of someone without a disability or illness” (Singer). In general, under QALY “if a ‘high priority health care activity is one where the cost-per-QALY is low, and a low priority activity is one where cost-per-QALY is high’” then individuals with conditions that are cheap to treat are prioritized over individuals that require more expensive treatments (Harris 119). This system discriminates against groups of patients that unfortunately suffer from a disease that is expensive to treat. QALY requires physicians to systematically save specific groups of patients, at the expense of others.

Lastly, this method of valuing life does not create a distinction between life-saving and life-enhancing treatments. In general, most people think that life-saving treatments should take priority to life-enhancing treatments; however, that is not the case with QALYs. Instead, QALYs prioritizes individuals that have higher QALYs on average, meaning that they can live longer and at a higher quality of life. As a result, if a patient who is seeking a life-enhancing treatment has higher QALYs than a patient seeking a life-saving treatment, the patient with the higher QALYs would be prioritized regardless of the treatment that they are seeking.

Calculating QALYs is also a debated topic because in order to calculate it, one must decide what the patient’s potential quality of life will be. As we have discussed earlier in this class, it is impossible for one to know how another individual would value their quality of life since we all have different experiences and values. Reflecting upon that, I think that the method of calculating QALYs is unethical because it involves making assumptions on another’s behalf that may not be entirely accurate.

Taking everything into consideration, while using QALYs would be beneficial in deciding which patient to treat first when the two patients in question are in all regards considered equal, it is not realistically practical since most two patients are not alike. Using QALYs as a method to decide which patient to treat first or which patient should be prioritized is not ethical as it discriminates against certain groups of individuals and forces an outsider to determine what the patient’s quality of life is. As a result, QALYs should not be used in health care.

Works Cited:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2013. Print.

Harris, John. “Qalyfing the Value of Life.” Journal of Medical Ethics 13.3 (1987): 117-23. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. 30 Mar. 2017.

Singer, P., J. McKie, H. Kuhse, and J. Richardson. “Double Jeopardy and the Use of QALYs in Health Care Allocation.” Journal of Medical Ethics. U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 1995. Web. 30 Mar. 2017.