In Howard Brody and Eric Avery’s Medicine’s Duty to Treat Pandemic Illness: Solidarity and Vulnerability, they conclude physicians have a duty to treat pandemic illness because there is “no single ethical foundation for a duty to treat that would be commensurate with the needs posed by an emerging infectious disease pandemic” (Brody, 42). While I respect and understand the reasons behind their conclusion and appreciate their consideration to individual commitments and social values, I do think they fail to speak to some other ideas in question such as, what does it mean to be a physician?

The authors claim “by announcing to the community they are practitioners of medicine, physicians implicitly accept and undertake these duties,” (Brody, 40) but this raises the fundamental question of what it means to be a physician. As mentioned in the article, some physicians reacted to the assumption of their duty to treat with thoughts such as “Wait a minute—I never signed up for this” (Brody, 42). This got me wondering, why do people become physicians? Is it for the “awe of discovering the human body, the honor of being trusted to give advice, the gratitude for helping someone through a difficult illness”, for the prestige of the “Dr.” title, for the financial means it provides, or for another reason (Ofri)? Whatever the reason may be, these few listed options make me question whether all physicians go into medicine so that they may “help people” as many of my pre-med colleagues would say. There are many different professions and roles people can take on to help people, and perhaps, people take on the role of physician for the science rather than the people-aspect. If that is the case, we could argue that they indeed did not “sign up for this (referring to endangering oneself for the sake of the patient).” That being said, “the tradition of the American Medical Association, since its organization in 1847, is that: ‘what an epidemic prevails, a physician must continue his labors without regard to the risk to his own health” (Daniels, 37). So, in a way, physicians should know what is expected from them. However, I acknowledge reality is not so black and white. Some physician specialties to consider are: anesthesiologist, cardiologist, dermatologist, endocrinologist, family medicine, forensic pathologist, hematologist, infectious disease specialist, neurologist, oncologist, psychiatrist, radiologist, sleep disorder specialist, sports medicine specialist and more. There are so many different types of physicians and each specialty has different degrees of exposure to hazard. I wonder if the strict adherence to the duty to treat would deter people from entering certain specialties innately more prone to hazards involved with pandemics (ie. infectious diseases, etc). There are many frustrations that come with the role of a physician including the short amount of time allotted to visiting patients and the documentation and technical duties that come with patient visits.

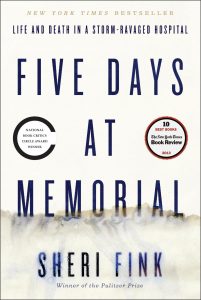

To read more on the debate over duty to treat, I recommend the book, which comes to mind called Five Days at Memorial by Sheri Fink. It is a book about Hurricane Katrina wreaking havoc and sending hospitals such as Memorial into a state of crisis. While some healthcare professionals flee the storm and leave behind patients, others stay at the hospital and continue giving care, working till exhausting and continuing despite being understaffed and having limited resources. This parallels the treatment of pandemics in that health care professionals put themselves in harms way.

I also recommend checking out this article, “Duty to Treat and Right to Refuse”, by Normal Daniels: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3562338?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

While I hope physicians take on the duty to treat no matter what, I ultimately still see the role of treating during pandemic as supererogatory. I see these healthcare workers as humans first, then physicians. If they want to prioritize their own health, family, or something else, they should be able to do that.

Citations

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Brody, Howard, and Eric N. Avery. “Medicine’s Duty to Treat Pandemic Illness: Solidarity and Vulnerability.” Hastings Center Report. The Hastings Center, 15 Jan. 2009. Web. 16 Apr. 2017.

Fink, Sheri. Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-ravaged Hospital. New York: Broadway, 2016. Print.

“Medical Specialists – Types of Specialists.” WebMD. WebMD, n.d. Web.

Ofri, M.D. Danielle. “Why Would Anyone Choose to Become a Doctor?” The New York Times. The New York Times, 21 July 2011. Web. 17 Apr. 2017.

Thomas, John E., and Wilfrid J. Waluchow. Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics. Peterborough: Broadview, 1987. Print.