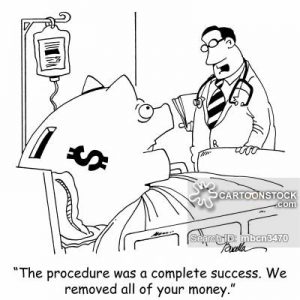

Martha and her partner are both unemployed parents of three children. After the failure of home remedies and realizing that she may have a serious oral healthcare situation, Martha decided to see a physician. To her dismay, though, she understood that she was not going to be able to get the real help she needed as she did not have dental care coverage or the government supplement to reduce the cost of the medical treatment. Martha decided to stick with her home remedies and hope for the best. In the more recent years, a serious issue amongst low-income families has arose. With the costs of healthcare rising and the rate of employment declining, more and more people are becoming uninsured and unable to afford healthcare for themselves and their families. This leads to the question of what to do about this rising issue. Currently, there are policies in place that help offset costs/provide minimal healthcare for children and disabled persons. Unfortunately, though, many people do not qualify under these circumstances to receive help. This leaves people stranded and without insurance.

Utilitarian arguments point in the direction of support for public funding that provides healthcare for all of these people. Which, if agreed upon, is absolutely doable and has been done before in other countries. One of the largest counterarguments to this, though, is the overwhelming “inverse relationships between socioeconomic status (SES) and unhealthy behaviors such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition” (Pampel). There has been enough credible research done that points out the fact that the vast majority of people that fall under lower socioeconomic status are less likely to carry out healthy practices. Essentially the argument is that they bring the health problems onto themselves. Many anti-supporters of this movement believe it would be a waste of money to invest in healthcare for these persons, as they are going to cost the people and the government too much money due to their unhealthy habits.

While this argument is not necessarily invalid, it is important to realize the correlations between low socioeconomic status and lack of education. It is very likely that many of these people who practice these unhealthy habits are not educated in what is healthy and what is not. I’m sure many of them wouldn’t smoke a pack a day if they were aware of the severe health risks. Ethically, it is wrong that people must be excluded from receiving healthcare to keep them healthy and alive just because they cannot afford it. The right to be a healthy individual is not and should not be considered something that only the wealthier members of society are entitled to. Providing healthcare to all citizens of your government should be a top priority for all countries, as health people are happy people and you have the potential to stop this epidemic of unhealthy poverty stricken areas.

There is even research that shows children with low socioeconomic status are more likely to get sick. This is why it is unethical not to provide healthcare for people of low SES.

Works Cited:

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Pampel, Fred C., Patrick M. Krueger, and Justin T. Denney. “Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors.” Annual Review of Sociology 36.1 (2010): 349-70. National Library of Medicine. Web.

Thomas, John E, et al. “Case 2.2: Social Determinants of Health.” Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics, Broadview P, 2014.