Dilemma:

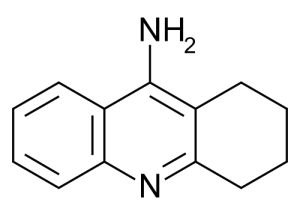

A researcher is attempting to conduct an experiment of a new Alzheimer’s drug that may reduce progression of the disease. According to the chemistry of the drug, the experiment calls for patients that may experience varying degrees of competency. To enroll a patient in the experiment, a patient must have written consent from the patient’s closest relative and healthcare staff in addition to his/her own. The patient must also be deemed competent, but if they are intermittently competent, the patient may be excluded from the trial. The director of the nursing home then responds to the researcher by not allowing any of the nursing home patients to be included in the experiment so that the vulnerable group is not exploited(Thomas). Was the director right in her choice of refusing the experiment all together?

Discussion:

Working through the case of whether or not elderly Alzheimer’s patients should be able to participate in an experimental drug trial raises numerous tricky questions that seem to have no precise answer. The question of consent is perhaps one of the trickiest dilemmas we face, and this case starts with three parties (the elderly person with Alzheimer’s disease, the family of said person, and the director of the St. Mary’s Nursing home) potentially being involved with the consent of one party. The end result of the director taking responsibility over consent of the elderly patients and denying participation of all patients was one I thought was not exactly the best course of action here. I can see her side of wanting to protect the patients from being overstressed or taken advantage of, but I also see her taking the freedom of those competent enough to possibly assist in production of a drug that could treat the very disease affecting them. I believe that choice of being included in the experiment should be mostly determined in the competent mind of the patient with minor focus on family choice assuming that the current physician of the patient confirms the competency as well. A competent patient affected by Alzheimer’s being denied the chance to aid in research that could treat Alzheimer’s could easily be compared to shooting yourself in the foot, yet in this specific case someone else is holding the gun. The very thing that could lead to better treatment of Alzheimer’s is being inhibited at the choice of someone other than those affected by it.

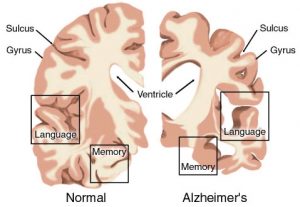

The major problem with determining consent is the definition of competency used, which leads me to the point of discussing a competency continuum in exchange for the quantized two choice system that is used as mentioned in the book. The fact that the patients are in varying stages of Alzheimer’s should intuitively lead to a varying degree of competency, and to group them into groups of incompetent or competent would be too simple.Though a continuum to match the gradient of competency might better suit the ethics of the experiment’s design, ultimately, the patient is still going to be grouped into two groups of either being in the experiment or not being in the experiment. While this competency continuum may be more practical in the ethics of healthcare treatment such that patients receive varying degrees of treatment, I do not see a real use of dividing the subsets of Alzheimer’s patients only to reduce them back into a two choice system. It is not as if the differing classes of competency will receive differing levels of participation in the drug trial; it is either the patient is in the experiment or not. In this case it would seem to create a special class for elderly patients who just want live a normal life and not one of being burdensome. In summary, I believe the nursing home director overstepped her authority such that competent elderly patients could not have a voice in their participation in the experiment even with competency confirmed by healthcare staff and family.

References:

1.Thomas, John E, et al. “Case 3.2: Nonconsensual Electroconvulsive Therapy.” Well and Good: Case Studies in Biomedical Ethics, Broadview P, 1987. 62-94.