Background of Assisted Suicide

For many, assisted suicide is a very sensitive topic. Some believe that suicide itself constitutes a form of a crime, while others believe that assisted suicide is a lawful act that should be legalized in the entire United States of America. In Is Suicide Murder by William Mikell, Mikell states that, “In English law…the deceased [one who committed suicide] is here punished with forfeiture, not for the crime of taking his own life” (JSTOR). On the other hand, the opposite point of view must also be taken into account. Although America does not currently legalize assisted suicide in all fifty states, America stands with the belief that all of its citizens deserve utmost freedom. Would assisted suicide not provide the preeminent standard of freedom? “Supporters of legislation legalizing assisted suicide claim that all persons have a moral right to choose freely what they will do with their lives as long as they inflict no harm on others” (SCU).

The Case

In this week’s reading, we have an ALS patient in the initial stages of the disease that wishes to be allowed the opportunity to commit suicide on her own volition when the time comes that she feels fit. The dilemma is that with ALS, the patient passes away when all organs fail to keep functioning and the heart stops beating. The patient’s solution to this problem is to ask to be provided with a device that she can have attached to her so that when the time comes, she can commit the action herself. In order to lawfully attach a device of this nature, Sue Rodriguez, a Canadian citizen, went to the Canadian court system to help her legalize this form of suicide. The courts denied her the allowance of this method of suicide. As a result, Sue when on to an anonymous doctor and had the doctor perform assisted suicide. Gloria Taylor, as second patient with ALS appealed to British Columbia’s court, and this time, the court could not make a decision, so appeals are currently in progress today.

Conclusion

The main concern with this particular dilemma is that as humans, we “have an obligation to relieve suffering of our fellow human beings and to respect their dignity” (SCU). If a patient is incarcerated to a hospital bed with a terminal illness that is extremely painful, as humans, how can we morally justify allowing the patient to go through the extreme amount of pain?

Alternatively, we also have the moral principle of non-maleficence. As humans, we are expected as moral beings to minimize harm as much as possible. By assisting in a suicide, the reduction of harm is completely ignored.

In the end, the dilemma comes down to one question: Should we harm for morals (assisted suicide, or not harm for another form of morality (non-maleficence)? What ought we to do?

The answer is not concrete for every case, but must be analyzed separately, case by case. In this particular case, in my opinion, in order to minimize the suffering the patient will be incurring, assisted suicide should be allowed. Let’s remember that the patient is the one suffering and the one committing the act of suicide. We ought to allow the patient to decide the morally justified ground of themselves in this case.

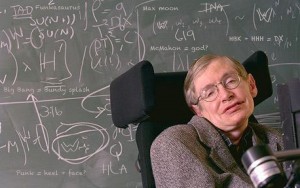

Infamous ALS Patient

Stephen Hawking is an astrophysicist with ALS. When he was diagnosed, he was told he had merely two years to live. That was in 1963. Hawking lives today, 52 years later, having given so much to this world.

Works Cited

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1109529?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

http://www.finalexit.org/assisted_suicide_laws_united_states.html

http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v1n1/suicide.html

In Case 6.2, “Sue Rodriguez: Please Help Me to Die,” the patient, Sue, is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. As per the ALS association, this disorder involves the progressive degeneration of motor neurons, which affects cells in the spinal cord as well as the brain. This degeneration results in diminished muscle movement, and the muscles atrophy. Symptoms include muscle weakness in the arms, legs, swallowing, etc. The average life expectancy for patients with ALS is two to five years after diagnosis although it varies from person to person. After being diagnosed with ALS, Sue has asked for a medical professional to help her with committing suicide before the disease takes her life.

In Case 6.2, “Sue Rodriguez: Please Help Me to Die,” the patient, Sue, is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which is also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. As per the ALS association, this disorder involves the progressive degeneration of motor neurons, which affects cells in the spinal cord as well as the brain. This degeneration results in diminished muscle movement, and the muscles atrophy. Symptoms include muscle weakness in the arms, legs, swallowing, etc. The average life expectancy for patients with ALS is two to five years after diagnosis although it varies from person to person. After being diagnosed with ALS, Sue has asked for a medical professional to help her with committing suicide before the disease takes her life.