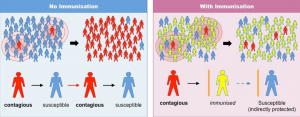

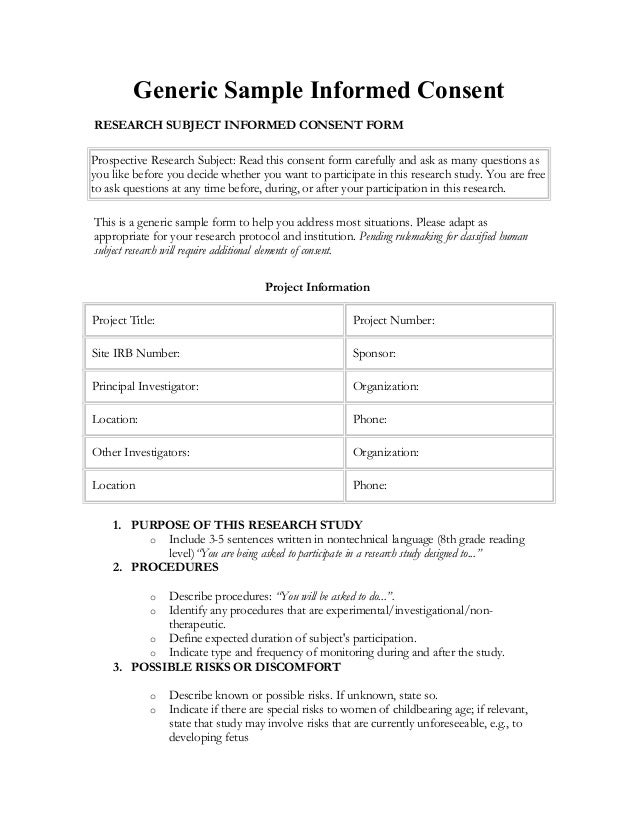

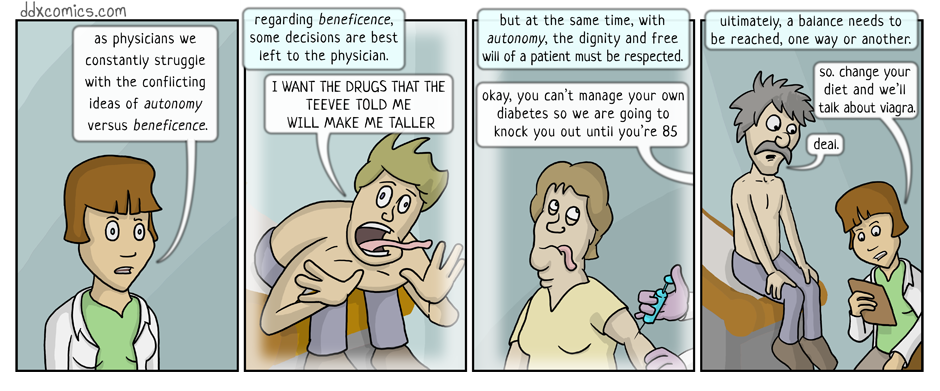

Do immunization mandates sacrifice patient autonomy for the benefit of public health, and if so, is this a justifiable tradeoff? Responsible governing bodies and healthcare providers are obligated to maximize a patient’s ability to make an informed, autonomous decision, while also promoting beneficence for both the individual patient and the group (i.e. overall population). Immunization — generally achieved through vaccination — presents a challenging case for balancing autonomy with individual and group benefit. This is further challenged by the fact that overall immunization efficacy is partly dependent on the percentage of the population inoculated, or herd immunity. The benefits of immunization are not solely confined to the individual and thus it is in the interest of the government and healthcare providers to act on behalf of the collective group.

In the past, immunization was mandatory by using it as a requirement for participation public education. The mandating of certain childhood vaccinations reduces parental autonomy by creating an undesirable alternative to non-compliance. Though this policy was once effective as making vaccination a de facto requirement for American children, state exemptions have made it relatively ineffective.

Some states view vaccination as a procedure that conflicts with certain ideologies. As a potential violation of religious freedom and patient autonomy, religious and personal belief (philosophical) vaccine exemptions were adopted in many states. In fact, California, West Virginia, and Mississippi are the only states that do not have at least one of these exemptions for school enrollment (1). These three states do however provide medical exemptions for rare instances of patients who have been deemed unfit for receiving vaccination. While the religious and personal belief exemptions are designed to return greater autonomy to the patient, these laws have subsequently undermined immunization efficacy and the overall population safety.

After decades of effort to eradicate lethal communicable diseases, the government has seemingly abandoned its ability to enforce universal medical policy, rather choosing to prioritize maximizing patient autonomy. The effects have been noticeable; measles, once thought to have been eradicated from the United States, has returned with the liberalization of patient autonomy policies regarding immunization (2). Yet despite the return of some diseases, opponents to mandatory vaccination have been willing to challenge the underlying safety of vaccines as defense of their position.

These vaccination debates have persuaded some — with or without factually justifiable arguments — to utilize the vaccine exemptions for their children. Past failures in vaccine synthesis and storage, along with egregious errors in administration protocol (i.e. Egypt’s Hepatitis C needle sharing and subsequent Hep C outbreaks) provide precedents for vaccine-skeptics to justify their stances (3). While many of these arguments rely on straw man and falsely-equivalency fallacies, plenty of people are willing to disregard logical coherence for emotionally persuasive arguments. While rhetorical strategy is not of direct relation to the dilemma of balancing autonomy with beneficence, the dissemination of such fallacious arguments poses as a threat to maintaining vaccine compliance when broad exemptions are available. Safe levels of preservatives likes thimerosal will continue to be investigated, along with risk-benefit analyses of vaccination being included to challenge exemptions by demonstrating the collective risk induced from marginal gains in patient autonomy. Sadly, absurd straw man arguments like “vaccines cause autism” detract from legitimate discussion regarding the government’s role in minimizing disease risk through compulsory immunization. Vaccine exemptions as they currently exist have been abused and demonstrate the need for a revitalized focus on population health.

While I agree that it is the role of the government to enforce public health policies that seek to reduce and eradicate diseases from the population, the slippery slope of government involvement in healthcare continues to be of legitimate concern for many. There are examples of medical procedures that have been deemed illegal on moral grounds, like abortion. As popular opinion changes and politicians react to constituent demands, it does not appear to be unrealistic that hysteria regarding certain medical procedures could be used to defend either strict mandates or inappropriate exemptions that greatly sacrifice autonomy and beneficence, respectively.

If there has ever been an example where a measured amount of individual autonomy can be curbed for the group benefit, mandatory immunization is certainly a defensible policy. However, discourse indicates growing skepticism towards the pharmaceutical industry and the government’s intentions. Growing resentment towards political lobbying — particularly against the villainized pharmaceutical industry — along with increased immunization exemptions present an unsettling trend in the government’s abdication of its authority over public heath policies.

With extensive peer-reviewed research, FDA trials, and concrete examples of the risk imposed by non-medical immunization exemptions, the government should not feel compelled to expand parental autonomy over childhood vaccination. Empirical evidence supports strict immunization laws; hysteria and fallacious arguments promote exemptions. With solid empirical support and clear examples of risks, it is the responsibility of our political leaders to stay informed and act in accordance with the best policies for their constituents. We can only hope that the many such cases of empiricism and reason lead our discussion, and not fear-promoting, fallacious arguments.

https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/449525268529815552

Sources

1.States with Religious and Philosophical Exemptions from School. NCSL. Online. Accessed 22 March 2017 <http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/school-immunization-exemption-state-laws.aspx>

2. Mnookin, S. The Return of Measles. Boston Globe. Sept 29 2013.

3. Miller, FD. Elzalabany MS, Hassani S. Cadres D. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus exposure in Egypt: Opportunities for prevention and evaluation.World Journal of Hepatology. 2015. 28: 2849-2858.