Background: One of the biggest issues that I see in our society is the unwillingness of the populace to engage with their beliefs that they hold so dear. The issue of physician assisted suicide is one of the most under discussed and consequently least understood issues of our time. The Society’s inability to separate from its dogmatic beliefs leads to a very myopic discussion about the ethics of physician assisted suicide. This problem has very harsh consequences on patients that are suffering from incurable and often very painful diseases. The case of Sue Rodriguez is such and I find it rather troublesome that the court decided against her wishes. Sue suffered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a decease that leaves its victim unable to speak, walk, and ultimately kills by paralyzing the respiratory system (Thomas).

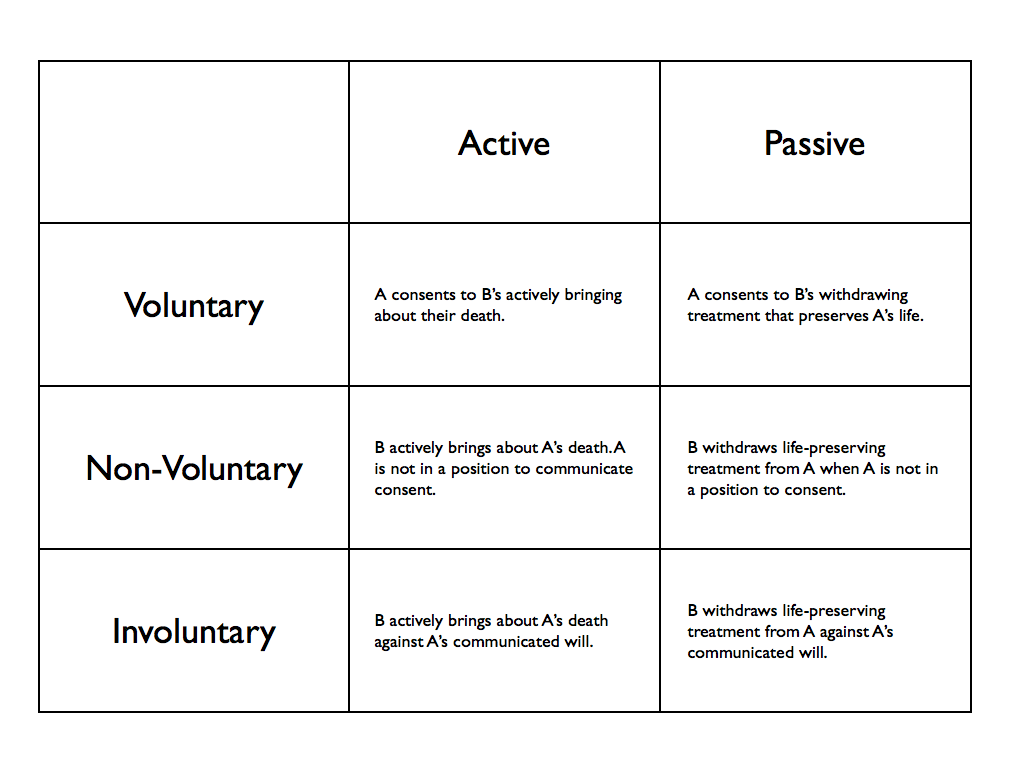

Moral Issues: The case presents several moral issues regarding the issue of physician assisted suicide. Arguments against it as listed in Well and Good book are:

- Pain can always be managed through strong analgesics.

- It will result in diminished efforts to improve end of life care for other patients.

- It is a form of killing and inconsistent with physician’s duty to never harm.

- Slippery slope to involuntary euthanasia.

Discussion: One of the greatest advocates of physician assisted suicide, Dr. Kevorkian often said that it is absolutely inhumane for an advanced society to not allow its members who are suffering from incurable and painful diseases to not end their lives. The biggest and the foremost argument in favor of it would be respect for patient autonomy. Choosing what happens to one’s life is very fundamental to being autonomous and the government should not have any say in that regard. Another not so straightforward argument would be the principle of non-maleficence. While aiding to someone’s death is clearly contrary to the principle, I would argue that intentionally forcing patients to suffer though extreme pain, especially when they do not have any potential to get better clearly violates the principle of non-beneficence. Of all the arguments against physician assisted suicide mentioned above, I would like to focus more on the last one as it presents quite unusual challenge when it comes to public policy. The issue is that it will blur the line between right to die and the expectation to die. Opponents argue that if society legalized the act of assisted suicide, it will gradually become an expectation for terminal patients to go through with the option of committing suicide. This claim does have some legitimate merits to it and should be carefully studied and discussed. However, a study from Netherlands, where physician assisted suicide is legal, showed that for the past few years there has been a decrease in the number of people opting for physician assisted suicide, partly because of the change in approach by the Dutch doctors in pain management strategy (Van). A system that adequately addresses this issue must be set in place for carrying out the practice of physician assisted suicide. I encourage you guys to have these conversations with people around you and spread awareness regarding this issue so that we address it and do justice to all the helpless patients throughout the country.

Work cited:

Thomas, John E., Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2014. 214-22. Print.

Van Der Heide, Agnes. “End-of-Life Practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act.” ProQuest. N.p., 10 May 2007. Web. 18 Feb. 2017.