Hi fellow PHIL 116 classmates and bioethics blog readers! I recently watched the short film, Extremis, on Netflix and as it is both a quick watch and very relevant to our course, I recommend it to all of you! To get an idea of the film, the trailer is below:

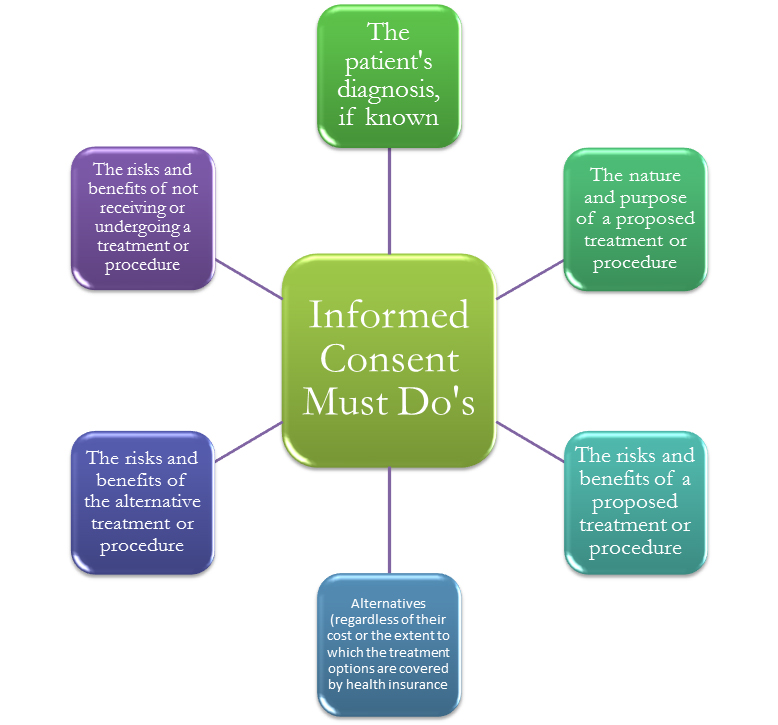

In a mere 24 minutes, Extremis follows the lives of a few patients and their families who are on breathing tubes, feeding tubes, and other forms of life support. The filmmakers did an excellent job demonstrating the opinions and challenges faced by physicians, surrogate decision makers, and the patient’s themselves. It addresses patient autonomy (or lack thereof) of patients who may not be able to express their end-of-life wishes. It also demonstrates the tug between prolonging life, which may do more harm than good, and ending it, which may have other ethical implications.

*SPOILERS AHEAD*

I found it fascinating that the different families, all with similar situations, each had a different opinion on how to treat their dying family member. For example, in Donna’s case, her family opted to remove her from the breathing tube and she died one day later. This decision, while challenging and emotional, was the right decision in my opinion. As shown in the documentary, Donna communicated a clear dislike of the breathing tube and a general understanding that if removed from the tube, she would die. Her family also informed the doctor’s that she had discussed end-of-life care before and was comfortable with removal of machine support.

However, in Selena’s case, her daughter equates removing life support with murder and so her mother is hooked up permanently to a breathing machine and dies six months later. A family of strong faith, Selena’s daughter and brothers are hoping for a miracle. However, when we look at these cases, I wonder if those extra six months actually brought joy or benefit to the patient herself or simply removed the guilt from her surviving family. The film states at the end that she survived with a few periods of consciousness – but did that add to her quality of life?

All in all, it was a very thought-provoking film for me as we have been discussing these types of issues the entire semester. I encourage you all to watch and post your thoughts below!