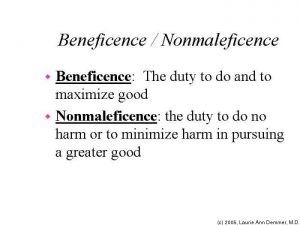

Both non-maleficence and beneficence are concepts that are universal across our world, whether it is in everyday actions or in a healthcare setting. However, to what extent is non-maleficence and beneficence universally recognized? We can analyze this question by delving into the motives and virtues of multiple cultures across the world and we can compare and thus contrast the aspects of non-maleficence and beneficence.

As we can see across the United States and in most western countries, non-maleficence and beneficence across a health care setting derives from the relationship between the doctor and his/her patient. Across history, our doctor-patient relationship in the United States has changed towards greater respect for patient’s autonomy rather than a historically paternalistic ideology. There needs to be much more consent from the patient before any type of medical procedure is placed upon the patient. Even in bioethics class, we place the importance on the consent of the patient and the patient’s autonomous decision.

In the sense the word “beneficence” is a type of paternalism in which the doctor assumes what is beneficial towards the patient. In many other cultures beneficence is actually emphasized more than autonomy. There has shown to be correlations between the type of government and the power of beneficence over autonomy. Pellegrino and Thomasma’s article asserts that this could be as a result of many different factors, of which includes technology, religion, economy, and politics.

Accordingly, in Islamic medical ethics, there has been studies done on the works of Mawlana, a prominent Sufi theologian and philosopher, that showed that beneficence is prioritized over autonomy. We also see that religion is a major factor when considering the emphasis of beneficence with Confucianism in China. Beneficence is emphasized greatly as “A humane art, and a physician must be loving in order to treat the sick and heal the injured” (Kao, 2002). Politics also play in a major role when considering beneficence. The world’s “democratization” carries with it distrust for authority, and thus there seems to be a correlation between the United States of America’s democratic politics and the lowered respect for paternalistic beneficence of the physician in most healthcare settings. Technological advancements in our society is also something that can be greatly considered when thinking about autonomy versus beneficence. Technology in a sense brings about freedom within people. Having different cars, phones, and other forms of technology allows us to assume that we are autonomous beings who have great power in our own decisions. This in turn seems to be correlated with our western culture being more focused on autonomy.

Does looking into a cross cultural prospective of the principles and aspects of autonomy and beneficence in a bioethical lens helps us in a way? I would say that it helps us to generalize less about “an individual” and to realize that there are many complicated factors when considering balancing autonomy of the patient and beneficence of the physician. I would love to hear comments and thoughts about this topic.

Works Cited:

Pellegrino, Edmund. “The Conflict between Autonomy and Beneficence in Medical Ethics: Proposal for a Resolution.” Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2017.

“Non-Maleficence and Beneficence.” The EIESL Project RSS. EIESL Project, n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2017.

“Ethics – Definitions and Approaches – The Four Common Bioethical Principles – Beneficence and Non-maleficence.” Alzheimer Europe. Visual Online, n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2017.

Beauchamp, Tom L., and James F. Childress. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.