By Anna McDonough, Andi Breitowich, Caleb Shulman, & Harshit Patel

Walking down the aisles of the grocery store can be a daunting task. Various labels are branded onto packaging, and while a majority of people look at food labels seeking the health benefits of a product, over half are unable to pick out those desired beneficial nutrients or decode what these labels truly entail (Loria). This might seem to be a startling statistic, but think of your own shopping experience. You might consciously choose to purchase the organic “mac n cheese,” or the non-GMO cereal, but why? What makes the organic version better than the non-organic, and why is it more expensive? Oftentimes, we just accept these labels and appreciate the status, yet there is still considerable confusion about the true health benefits or lack thereof. Perhaps the confusion stems from a sense of apathy, or maybe we as a society are uneducated about the true representation of labels and how to properly draw out the beneficial information. These questions all stem from the broader world of epistemology, the theory of knowledge.

Epistemology, food, and a “good” life

Epistemology investigates the distinction between justified belief versus mere opinion. Food epistemology encompasses the justified knowledge of what is considered to be healthy and nutritional for the human body, what is “good” for us and what is considered to be an indulgence. In today’s day and age, there is an increasing desire to live a healthy, fit, balanced life in relation to body, mind and soul. The influence of food on healthy living trends and the impact of food labels urges us as consumers in a capitalist society to buy, consume, and ingest certain products. Certain labels carry heavy weight in what society considers to be supportive in achieving our goal of a “healthy” “good” life, yet do we really understand what these labels mean? Do we passively accept “organic” to be “good” for us or do we actively educate ourselves on the implications and benefits that these labels accurately mean? Because we are unable to verify precisely what we consume and how it was raised, prepared or cultivated, we are constantly vulnerable to misinformation. Nonetheless, consumers are willing to pay premium prices for the preferred labeled products that are presumed to have nutritional benefits. We are curious as to how these labels and their implications influence what it means to achieve a “healthy” and “good” life, yet overwhelmed by our own uncertainty in the knowledge of a “healthy” life. As over-scheduled and busy humans, we seldom consider that nutritional labels could be misinforming us with preconceived ideas of “average” daily values or that we have subconsciously associated labels with false ideas of what “healthier” choices might be. However, fact-checking every label that could decorate food products seems like an unrealistic expectation. The relationship between food labeling, acceptable pleasure, and our motivations as consumers to buy into the idea of living a good life, as influenced by marketing labels, is one which deserves specific attention. As members of society, we all strive towards living a long and fulfilling life, yet the epistemology of how we succeed in this goal warrants a deeper dive.

In order to consider epistemic agency in the context of buying and eating food, we must first understand the origins of epistemology. Believe it or not, the concept of “knowledge” was much simpler years ago, especially compared to how it is perceived today. Plato got the ball rolling by clearly distinguishing between knowledge and opinion, and Descartes followed suit by forming just two criteria for what knowledge is, what makes it knowledge, and that “it must be clear, and it must be distinct” (Boisvert & Heldke 103). With so many respected philosophers contributing to this study, defining knowledge seemed easy, and everyone thought in similar ways. This idea of epistemology became more complex, however, when Kant argued that all knowledge must be absolutely certain, or apodictic. Finally, philosopher David Hume constructed a hypothesis based on the separation between facts and values. This school of thought aligns best with our understanding of epistemology today, where facts are seen as objective knowledge and values are viewed as judgements (Boisvert & Heldke 103), but is it really ever that easy?

In addition to comprehending epistemology as a whole, it might be useful to discuss priorities and the unique role they play in defining a “healthy” lifestyle. Everyone has priorities, and in general, we tend to conduct our lives based on these priorities and what we each deem to be most important. It is something we all subconsciously do, especially as students who are often assigned a variety of tasks and left to decide what to complete first. However, prioritizing what and how to eat is a dilemma we constantly reevaluate. What if I were to ask you “what is it that you prioritize when you think about food?” The messiness of food philosophy is partly due to the fact that most people are unclear of their priorities in regards to food, or what it would even mean to set out priorities in this manner. For the most part, people go to local grocery stores to do their food shopping, which could be the perfect place to begin consciously thinking about our priorities. Our decisions in the grocery store may be influenced by taste, price, health, time of preparation, how long until the food expires, recommendations from family or friends, the amount of people it can feed, or a combination of all of the above. This non-exhaustive list of factors that could influence one’s agency in the store is precisely why it is so hard to prioritize our food concerns. However, it does highlight the idea that knowledge and values are integral to defining our health both personally and holistically.

Oftentimes, shoppers’ problems stem from what they know and what they value. Issues regarding knowledge and values are extremely complicated and can differ for each individual shopper. Let’s consider the statement given by Boisvert and Heldke, for example, that “tomatoes are nutritious” (Boisvert & Heldke 104). On the surface, this is a very basic and elementary statement. Tomatoes are fruits or vegetables, depending on how you look at them – however, this is a claim that is both evaluated and factual. Epistemology itself combines the elements of aesthetics and ethics, and the only true way to answer questions related to this topic, as it says in Philosophers at Table, is to take its value dimensions very seriously. Furthermore, there is an “is-ought” fallacy that addresses our inability to separate what “is” it that we really desire from what we “ought” to want. As a result, we often convince ourselves that we always want the right thing, while this might not be true. This fallacy is seemingly omnipresent when food shopping. As we peruse the aisles and fill our carts, without even thinking about it, we find ourselves considering what it is that we truly want to buy and consume versus what it is that we should purchase. These can be two very different items, but something compels us to make the final purchases – our values. We have a hierarchy of food related values, which could be directly correlated to the knowledge, or the lack thereof, acquired for a specific product. If we were to go grocery shopping based solely on factual evidence and what we know to be true, we would have to metaphorically separate our head and heart, moving away from everyday routine. When facts become value free, we become distant and removed from the notion, importance and codependence of values and knowledge in our everyday lives.

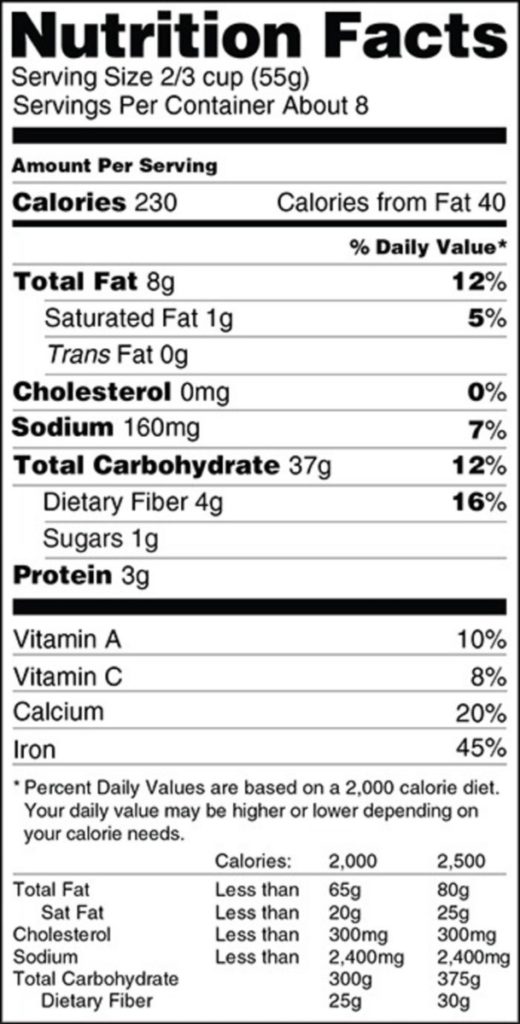

Modern consumers are frequently driven towards what is “right” or “good” or, in this case, “healthy” based on facts. In regards to food, nutrition labels are generally the first place consumers look due to their availability and accessibility. Often, when making decisions about what is healthy or good for us, we look for core values, such as total calories, carbs, or fats, and ignore the rest of the label. Think of your own experiences; how often have you stopped to think about these labels and values in depth? What do they consist of, what is left out, and what ought to be reconsidered? These questions lead us to dive deeper and focus on nutrition labels, while attempting to debunk fact-laden knowledge and its direct association with healthy living and achieving a “good” life.

To understand how nutrition labels shape the notion of healthy living and the good life, we must first take a step back and examine the individual components. The creation of a nutrition label is centered around a generalization, or recommended source of nutrients one should consume per day, also known as a daily value (DV). This daily value consists of serving sizes, calories, micronutrients, and macronutrients. The use of a numbers-based label leads the modern consumer to see fact-laden values as being superior to value-laden facts (Boisvert & Heldke 104). This rationale stems from the idea that fact-based values allow room for generalization as opposed to a person-specific recommendation, which would be far more difficult to distribute in the globalized economy. However, this generalization is based on the model of an “average” person, which simply does not exist. There are various characterizations such as height, weight, daily exercise etc, that create an individual’s identity and nutritional needs, yet we find ourselves geared towards and societally obsessed with nutrition labels. One must come to understand that while these generalized facts might begin to form an initial understanding of healthy living, a concrete image does not form until specifically applied to the self. As Boisvert and Heldke contend, this reiterates the necessity and importance of understanding the combination of both fact-laden values and value-laden facts (Boisvert & Heldke 111). People, myself included, must begin to use both forms of facts conjointly rather than viewing them on mutually exclusive terms. Only then can we use nutrition labels to form a better understanding of healthy living in relation to achieving our individualized “good life,” rather than catering our needs based on this imaginary “average person.”

Epistemic agency

With the sentiment of coexisting values when forming our own understanding of healthy living, we must create a holistic understanding, rather than an image of solely fact-laden values. This image, often dictated by the imaginary, relies on a lack of epistemic agency by the consumer. Epistemic agency, one’s ability to form knowledge, often gets superseded by the understanding that being informed equals being knowledgeable. Being informed simply denotes having information at hand, but being knowledgeable denotes a comprehensive grasp and understanding of the material. Nutritional labels, provided by companies with clever marketing schemes, offers an astounding wealth of information, but the displayed information tells us little in truth. This information is frequently quickly read and then understood by the consumer to have a solid understanding of the food. This notion reinforces the consumer’s idea of having a high epistemic agency in regards to their food choices, yet the nutrition label misleads and neglects to display other pertinent information. For example, when it comes to sugars, which are often regarded to be unhealthy by today’s standards, companies will use the strategy of boasting that there are “zero added sugars”. However, what people fail to take into consideration is the copious amount of natural sugar within the product, which can have different effects depending on the person. For some, such as a person with diabetes, these natural sugars may be detrimental to their health, while others might benefit from the sugars association to cancer risk reduction.

The understanding of an ingredient’s true nutritional value can sometimes come off as too complex. For example, how should one know ascorbic acid to be vitamin C? Here, the consumer might know the common name of the ingredient but lacks a thorough understanding of its cause and effects. Moving beyond the contents of the nutritional label itself, companies often provide scant information as to how their products are processed from the beginning stages of production to its ultimate in store shelf life. Thus, nutritional labels frequently paint an illusion of extensively and expansively informing consumers, while true knowledge regarding food products often goes unattained.

Clearly, nutrition labels shape the notion of healthy living with the ultimate satisfaction of obtaining a good life. However, these labels are often coated through a web of deceit that becomes more difficult to unlearn and better thoroughly understand. Whether it be health fads, diets, or sudden lifestyle changes, the use of nutrition labels are used and associated to the justification of how one ought to eat and subsequently live. Marketing schemes of sly corporations, within the globalized and mass-producing capitalist economy, affects the majority of society, plaguing them with deceit. While the methods of mass-production offer limited room for the modern consumer to understand and apply specialized and individualized daily values and intakes, the promotion of the imaginary “average person”continues to be upheld. Nutritional labels take advantage of a preference for facts and creates an illusion of informed epistemic agency. As a result, problems arise when relying on nutritional labels alone, thus reinforcing the initiative individuals must take to cater toward themselves, rather than relying on the “expertise” of the corporation behind the label.

How food labels impact consumer behavior

To further understand the influence labeling has on our notions of a “healthy” lifestyle, it is necessary to dissect the meanings of these often ambiguous labels and in turn how they impact consumer behavior. In recent years, it seems as though food labeling tactics beyond the nutrition facts have become more widespread and cater specifically to health-conscious consumers with unfulfilled promises of various health benefits. Brands strategically use labels aside from the aforementioned nutrition facts, such as “refined sugar-free,” “non-GMO,” “guilt-free,” and “organic,” among hundreds of others, to appeal to shoppers who have learned to associate these seemingly arbitrary distinctions with nutritional value. However, if we ponder the meaning of “organic,” for example, the uselessness of this label as a marker of nutritional content becomes abundantly clear.

In 2018 alone, organic food sales increased by roughly 6% to reach $47.9 billion (Gelski), but what exactly are you paying for when purchasing a product with the alluring USDA-certified-organic seal? Depending on who you ask, “organic” takes on a multitude of incorrect meanings. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is the governing body that administers the coveted seal, organic products have been “ grown and processed according to federal guidelines addressing, among many factors, soil quality, animal raising practices, pest and weed control, and use of additives” (McEvoy). The emerging market of organic processed goods only further complicates this meaning – to be stamped with the “made with organic ingredients” seal, a product must only contain 70% certified organic goods (McEvoy). While the process a farm must undergo to be certified by the USDA is quite extensive and requires annual inspections, the definition of organic available on the USDA website is vague and gives little insight into what one is actually consuming by choosing organic.

Consumers undoubtedly have their own motivations to choose organic produce, but, in general, there is a prevalent belief that organic products are more nutritious, safer, and of improved quality. Some 56% of consumers are under the impression that organic products have better nutritional content while nearly 50% of organic shoppers believe the products they purchase are fresher (Amaditz). I asked my dad what motivates him to buy organic turkey, for example, and he said he thought it was lower in fat. While the practices used to cultivate organic produce, meats, and processed goods may be safer in that they use fewer pesticides, herbicides, and additives, there is no mention of improved nutritional content or health benefits in the USDA certification process. Why did consumers learn to equate the environmentally-friendly farming practices that yield organic products to “healthier” choices? Further, if labels do not tell the whole truth, then how can consumers have full epistemic agency when purchasing food?

Trust and testimony in food labeling

In her book Thinking Through Food: A Philosophical Introduction, Alexandra Plakias flirts with similar questions and more specifically analyzes the unique roles of trust and testimony in food labeling. As we question the integrity of labels, whether it be the USDA-certified organic stamp of approval or the plethora of unregulated labels that appeal to the health-conscious consumer, it is imperative that we grasp the purpose of labels. As Plakias points out, brands use labels to sell products not because they are concerned with what the consumer believes about the product. Yet, that is not to say labels are intended to be deceptive – instead, they are used to “bullshit” the consumer into buying products (Plakias 26). Recognizing that the labels are intended to sell products and not necessarily tell the whole truth is liberating in some sense, but invites us to question what information we can trust when making choices about what we eat.

Because we are unable to verify exactly what we consume, we are constantly vulnerable to misinformation. Although, Plakias reminds us that this position of vulnerability does not always lend itself to trust (Plakias 23-25), and again, we are left to wonder how to make fully informed decisions when it comes to food consumption. If we rely on testimony, do we automatically trust the source of the testimony? Should consumers be responsible for exploring the reliability of every source? Should we be fact-checking all of the labels that decorate food products in order to have full epistemic agency? The reality is we often do not consider that labels could be misinforming us or that we have subconsciously associated labels with false pretenses of “healthier” choices. Although we do not actively consider the implications of this innate epistemic vulnerability, it is still a relevant issue that unfortunately affects how we interact with food.

As discussed, the relationship between food labeling, acceptable pleasure, and our motivations as consumers welcomes a great deal of thought. As members of society, we all strive towards living a long and fulfilling life, yet the epistemology of how we succeed in this goal warrants attention. Whether it be better understanding nutritional labels, taking note of our individual health needs, or having a firmer grasp of our epistemic agency, the philosophical world of food is a messy one that requires meaningful thought and self understanding.

Works Cited:

Amaditz, K C. “The Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 and Its Impending Regulations: A Big Zero for Organic Food?.” Food and Drug Law Journal, vol. 52, no.4, 1997, pp. 537-59. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10346680/

Boisvert, Raymond D. and Heldke, Lisa. Philosophers at Table: On Food and Being Human. London: Reaktion Books, 2016.

Gelski, Jeff. “U.S. Annual Organic Food Sales near $48 Billion.” Food Business News RSS, 20 May 2019, www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/13805-us-organic-food-sales-near-48-billion.

Loria, Keith. “Too Many Labels Cause Information Overload for Consumers.” Food Dive, 18 May 2017, https://www.fooddive.com/news/too-many-labels-cause-information-overload-for-consumers/442972/.

McEvoy, Miles. “Organic 101: What the USDA Organic Label Means.” USDA, 13 Mar. 2019, www.usda.gov/media/blog/2012/03/22/organic-101-what-usda-organic-label-means.

Plakias, Alexandra. Thinking Through Food: A Philosophical Introduction. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2019.