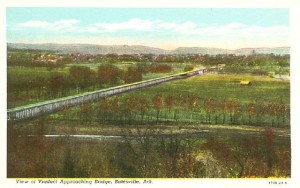

I am recently returned from a road trip to Arkansas, a place I have been traveling to-and-from for as long as I can remember. In some ways, the journey itself provides a “destination-on-wheels,” a predictable pattern of gas stations, small town cafes, and soybean fields that leads to Batesville, Arkansas, a town with a population of just over 10,000 people (2010 Census Data, American FactFinder). Sidney Mead once described Americans as a “people in movement through space,” exploring both “obvious highways” and “unexplored and devious byways” (ix). Understanding Wanderlust as a problematic birthright of sorts, I often feel most “American” when traversing the country by car, subconsciously moving through Chidester and Linenthal’s three interconnected domains; natural environments, built environments, and the mythic orientations that spaces engender (12). While scholars of religion have moved beyond the stark binaries of sacred/profane and center/periphery, preferring terms that situate space within constellations of political, social, economic, and symbolic power, for me, traveling to Arkansas has become a ritual journey from an unspecified somewhere to a holy nowhere.

I am recently returned from a road trip to Arkansas, a place I have been traveling to-and-from for as long as I can remember. In some ways, the journey itself provides a “destination-on-wheels,” a predictable pattern of gas stations, small town cafes, and soybean fields that leads to Batesville, Arkansas, a town with a population of just over 10,000 people (2010 Census Data, American FactFinder). Sidney Mead once described Americans as a “people in movement through space,” exploring both “obvious highways” and “unexplored and devious byways” (ix). Understanding Wanderlust as a problematic birthright of sorts, I often feel most “American” when traversing the country by car, subconsciously moving through Chidester and Linenthal’s three interconnected domains; natural environments, built environments, and the mythic orientations that spaces engender (12). While scholars of religion have moved beyond the stark binaries of sacred/profane and center/periphery, preferring terms that situate space within constellations of political, social, economic, and symbolic power, for me, traveling to Arkansas has become a ritual journey from an unspecified somewhere to a holy nowhere.Between the 1920s and 1950s, Batesville’s courtroom was the site of public religious debates, continuing a rhetorical tradition that emerged out of the Second Great Awakening and which flourished during the Restoration Movement. Importantly, these revivals resulted in the eventual formation of the Church of Christ, an evangelical sect that has long competed with independent Baptist congregations for church members among Batesville evangelicals. The 1980 Religious Congregations and Membership Study listed independent Baptist and Church of Christ congregations as mainstays of the Evangelical Protestant community that constituted 42% of the overall Independence County population, a number that grew to 72% by 2010. As non-mainline majority stakeholders in Batesville’s church scene, the Baptists and Church of Christ engaged in subtle religious rivalry, of which the public courthouse debates were perhaps the most conspicuous evidence.

My grandfather remembers these debates primarily as opportunities for Baptist and Church of Christ preachers to promote their denominational doctrine. In particular, he recalls that members of each denomination would sit on opposite sides of the courtroom, listening to the formal debate. Often, local ministers would debate one another, but traveling preachers also participated and were celebrated for their mastery of scripture and denominational doctrine. Two prominent preachers that held debates in the Batesville courtroom included Baptists Ezekiel “Zeke” Sherill (1875-1960) and Benjamin Marcus Bogard (1868 – 1951).

These two men participated in over 250 debates each, contributing to a complex network of local and regional conversations that took place in public spaces, including town and county courthouses. There is no official record of the debates, as they were not part of any legal proceedings, but it’s possible to find traces of this inter-denominational “discourse” in local newspapers and in the memories of devout octogenarians. In my grandfather’s memory, the debates were civil and never resulted in any actual change of opinion. Instead, they functioned as an important community ritual that regularly defined the doctrinal spaces of each denomination. The debates were always scheduled for Sunday afternoons, when the courtroom itself became a shared space in which religious difference could be explored, although never overcome. This marks an important distinction from the role that the courtroom plays as an arbiter of sacred space, as in the case studies of Michaelson, Taylor, and Glass. While American courts have a long and complicated history of adjudicating sacred space outside of the courtroom, the sacred space of the courtroom itself also warrants investigation.

These two men participated in over 250 debates each, contributing to a complex network of local and regional conversations that took place in public spaces, including town and county courthouses. There is no official record of the debates, as they were not part of any legal proceedings, but it’s possible to find traces of this inter-denominational “discourse” in local newspapers and in the memories of devout octogenarians. In my grandfather’s memory, the debates were civil and never resulted in any actual change of opinion. Instead, they functioned as an important community ritual that regularly defined the doctrinal spaces of each denomination. The debates were always scheduled for Sunday afternoons, when the courtroom itself became a shared space in which religious difference could be explored, although never overcome. This marks an important distinction from the role that the courtroom plays as an arbiter of sacred space, as in the case studies of Michaelson, Taylor, and Glass. While American courts have a long and complicated history of adjudicating sacred space outside of the courtroom, the sacred space of the courtroom itself also warrants investigation.

Vestiges of this specific use of the courtroom are hard to locate today, although one visual aid vividly reminds courthouse visitors of the building’s lasting legacy of civil-religion. While some religious images and references in public spaces have generated national attention and controversy, most notably the Ten Commandments monument erected in the rotunda of Alabama’s state judicial building, others go quietly unnoticed, such as this sign located at the corner of Batesville’s courthouse.

Vestiges of this specific use of the courtroom are hard to locate today, although one visual aid vividly reminds courthouse visitors of the building’s lasting legacy of civil-religion. While some religious images and references in public spaces have generated national attention and controversy, most notably the Ten Commandments monument erected in the rotunda of Alabama’s state judicial building, others go quietly unnoticed, such as this sign located at the corner of Batesville’s courthouse.

Understanding the three spatial domains that Chidester and Linenthal introduce as co-existing realities that map onto and across spaces, I wonder what it means to inscribe words onto a courthouse and to “claim” it for a specific ideology. I also wonder what it means that no one seems to object. If we take seriously the “contested character of sacred space” (16), Batesville’s courthouse provides a contemporary example of a seemingly bygone era of assumed, homogenous religiosity. In traveling through Chidester and Linenthal’s “itinerary” (31), I am struck by the relationship between regional religious experience and competing national identities. In my own travels, through Arkansas and beyond (most notably Appalachia), I will continue to investigate both real and imagined spaces and their often contentious designations as “sacred” in the American landscape.