It is impossible for me to consider Wendell Berry and his fervent plea for sustainability rooted in faith, family, and farming without contemplating my own family land in the Ozark foothills of Arkansas. As the second generation “off the farm,” I am sympathetic to Berry’s claims about the possibilities for personal, collective, and ultimately environmental restoration within a “healthy farm culture” (43). In many ways, I am persuaded by Berry’s emphasis on farming as a sacred ritual that preserves “essential experience” (45) within an “energy community” of production, consumption, and return (85). While the correlation between production and consumption is perhaps self-evident in our consumer-driven economy, the “principle of return” is more complicated.

It is impossible for me to consider Wendell Berry and his fervent plea for sustainability rooted in faith, family, and farming without contemplating my own family land in the Ozark foothills of Arkansas. As the second generation “off the farm,” I am sympathetic to Berry’s claims about the possibilities for personal, collective, and ultimately environmental restoration within a “healthy farm culture” (43). In many ways, I am persuaded by Berry’s emphasis on farming as a sacred ritual that preserves “essential experience” (45) within an “energy community” of production, consumption, and return (85). While the correlation between production and consumption is perhaps self-evident in our consumer-driven economy, the “principle of return” is more complicated.

Describing a “succession” of values, ethics, and attitudes “handed down to young people by older people whom they respect and love,” (44) Berry defines farming as a seemingly closed circle of insiders, “culturally prepared” to perpetuate a rural lifestyle.  Critical to this agricultural vision is both the “old man” and the “young tree” that Berry finds and celebrates in Odysseus‘ epic homecoming (129). But going home is problematic in the real world. Berry historicizes the United States as the root of rootlessness, a country whose discovery “invented the modern condition of being away from home” (54). In contrast to Homer’s grand narrative that, in Berry’s analysis, affirms a return to the land, twentieth century migration patterns in the United States document consistent movement out of rural communities into urban centers. Today, Americans predominantly move from one urban center to the next, largely avoiding rural communities altogether. As Berry astutely demonstrates, this movement is both social and geographic–the American “success story” often leads away from home (160) and doesn’t necessarily privilege a return.

Critical to this agricultural vision is both the “old man” and the “young tree” that Berry finds and celebrates in Odysseus‘ epic homecoming (129). But going home is problematic in the real world. Berry historicizes the United States as the root of rootlessness, a country whose discovery “invented the modern condition of being away from home” (54). In contrast to Homer’s grand narrative that, in Berry’s analysis, affirms a return to the land, twentieth century migration patterns in the United States document consistent movement out of rural communities into urban centers. Today, Americans predominantly move from one urban center to the next, largely avoiding rural communities altogether. As Berry astutely demonstrates, this movement is both social and geographic–the American “success story” often leads away from home (160) and doesn’t necessarily privilege a return.

Writing from the center of his world in the marginal space of Henry County, Kentucky, Berry asks for “confirmation, amplification, or contradiction from the experience of other people” (160). My life’s journey thus far as a “world citizen” with rural farming roots both confirms and complicates Berry’s many assertions and ideals, but it is the “principle of return” that seems most complex. In asking us to return to the “perfectly human possibility” of the “old man and his farm” (191), Berry reminds me of Ricoeur’s hermeneutic that offers a return to naiveté, but only after substantial suspicion and interrogation. In fact, Ricoeur’s model of return within a closed hermeneutic circle provides an interesting parallel to Berry’s cyclical energy communities and to other ecological and environmental philosophies. While Ricoeur privileges educated critique, for Berry, education, specifically the land-grant college complex and its emphasis on specialization, has created a chasm between knowledge/experience and practical/liberal that precludes a valuation of “health” and “wholeness” (138) that might yield a “primitive” connectivity.

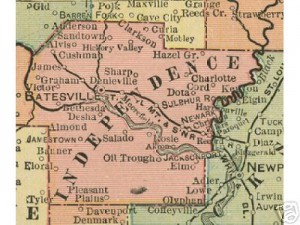

The disconnect between “traditional education” and farming has a long and storied history in my family. The story, as we tell it, involves an epic migration of the Gray family and their seventeen children, from western North Carolina to Arkansas in the nineteenth century, where they settled and quickly populated what became Independence County. The Grays settled on a tract of land with a fresh spring that could sustain a large family. My great-great grandfather, Christopher Columbus Gray, was one of “the original seventeen” and his decision to become a doctor, as opposed to a farmer, continues to inform the complex relationship my family has to its farming roots. Apparently,on their eighteenth birthday, each of the seventeen Gray children was given a choice between a college education and a tract of land. Some of the seventeen chose farming and today, many of their descendants continue to farm parcels of the original homestead. Others, however, including my great-great-grandfather, chose an education and profession that led them off the land. It is perhaps my great-great-grandfather’s decision to chose a professional career that prompts ambivalence in my grandfather, whose life journey precluded formal education and has been grounded on a farm he and my grandmother purchased when they were first married.

The disconnect between “traditional education” and farming has a long and storied history in my family. The story, as we tell it, involves an epic migration of the Gray family and their seventeen children, from western North Carolina to Arkansas in the nineteenth century, where they settled and quickly populated what became Independence County. The Grays settled on a tract of land with a fresh spring that could sustain a large family. My great-great grandfather, Christopher Columbus Gray, was one of “the original seventeen” and his decision to become a doctor, as opposed to a farmer, continues to inform the complex relationship my family has to its farming roots. Apparently,on their eighteenth birthday, each of the seventeen Gray children was given a choice between a college education and a tract of land. Some of the seventeen chose farming and today, many of their descendants continue to farm parcels of the original homestead. Others, however, including my great-great-grandfather, chose an education and profession that led them off the land. It is perhaps my great-great-grandfather’s decision to chose a professional career that prompts ambivalence in my grandfather, whose life journey precluded formal education and has been grounded on a farm he and my grandmother purchased when they were first married.

My grandfather is Berry’s quintessential “old man.” In recent years, he set out acres of young trees on the farm, unknowingly following Laertes famous example. Rooted in topsoil he has painstakingly nurtured, my grandfather has a body of knowledge about the land, gardening, and animal husbandry that could be the basis of Berry’s ideal intergenerational succession. The only problem is, my grandfather doesn’t particularly want his children and grandchildren to follow in his farming footsteps. Both of my grandparents pushed their children, my mother and uncle, off the farm, out of their small town, and right out of Arkansas. The American “success story” of mobility is what they envisioned for their children and grandchildren; so much so that I have struggled to convince my grandfather to let me farm with him. While my husband and I lived in Arkansas for two years, my grandfather and I had many conversations about my own visions for the farm. After two years of cajoling and pleading, my grandfather finally consented to the first step of what could have ben my “return:” we agreed that I would raise chickens in the back yard, potentially moving them (and, eventually us) onto the farm. That same week, however, I was accepted into the Graduate Division of Religion and, instead of learning to raise chickens and cattle with my grandfather, I am here, honing a different set of skills.

My grandfather is Berry’s quintessential “old man.” In recent years, he set out acres of young trees on the farm, unknowingly following Laertes famous example. Rooted in topsoil he has painstakingly nurtured, my grandfather has a body of knowledge about the land, gardening, and animal husbandry that could be the basis of Berry’s ideal intergenerational succession. The only problem is, my grandfather doesn’t particularly want his children and grandchildren to follow in his farming footsteps. Both of my grandparents pushed their children, my mother and uncle, off the farm, out of their small town, and right out of Arkansas. The American “success story” of mobility is what they envisioned for their children and grandchildren; so much so that I have struggled to convince my grandfather to let me farm with him. While my husband and I lived in Arkansas for two years, my grandfather and I had many conversations about my own visions for the farm. After two years of cajoling and pleading, my grandfather finally consented to the first step of what could have ben my “return:” we agreed that I would raise chickens in the back yard, potentially moving them (and, eventually us) onto the farm. That same week, however, I was accepted into the Graduate Division of Religion and, instead of learning to raise chickens and cattle with my grandfather, I am here, honing a different set of skills.

There are moments when I sense my grandfather’s regret and sadness that there is no one to continue his work on the farm. I hear it when he asks me whether I might “come home” one day. In that gentle question, I understand that my grandfather recognizes in his own body of knowledge a heritage and legacy of value. Nonetheless, neither he nor I know how to translate his experience into my future. While Berry points to industrial agribusiness as the culprit in marginalizing the small family farm, in my experience, that marginalization dates to my great-great-grandfather’s decision to pursue an education, a decision that considerably predates the era of Berry’s critique. It is that turn towards formal education that has my grandfather profoundly seduced. No matter how much I might want my grandfather to advocate for himself and his chosen lifestyle, he is no more required to encourage my “return” than I am required to enact it. How can we understand Berry’s plea for a return when, as in my situation, it doesn’t convict both young and old? How do we maneuver both the reality and ideal of the farm gate that, for me, represents an opening to a lifestyle in which I recognize my cultural heritage, but to my grandparents represents a powerful closure to a world of possibility that lies beyond the farm?

There are moments when I sense my grandfather’s regret and sadness that there is no one to continue his work on the farm. I hear it when he asks me whether I might “come home” one day. In that gentle question, I understand that my grandfather recognizes in his own body of knowledge a heritage and legacy of value. Nonetheless, neither he nor I know how to translate his experience into my future. While Berry points to industrial agribusiness as the culprit in marginalizing the small family farm, in my experience, that marginalization dates to my great-great-grandfather’s decision to pursue an education, a decision that considerably predates the era of Berry’s critique. It is that turn towards formal education that has my grandfather profoundly seduced. No matter how much I might want my grandfather to advocate for himself and his chosen lifestyle, he is no more required to encourage my “return” than I am required to enact it. How can we understand Berry’s plea for a return when, as in my situation, it doesn’t convict both young and old? How do we maneuver both the reality and ideal of the farm gate that, for me, represents an opening to a lifestyle in which I recognize my cultural heritage, but to my grandparents represents a powerful closure to a world of possibility that lies beyond the farm?