Everyone In Me is A Bird

Melissa Studdard

Mind was a prison, ruby lined

in its lipstick noir—everything woman

I was expected to be, trapped between

papered walls. What they said to do, I did not

but only levitated at the burning,

the body a water in which I drowned, the life

a windshield dirty with love. What they

said to think, I thought not but instead made

my mind into a birdcage with wings

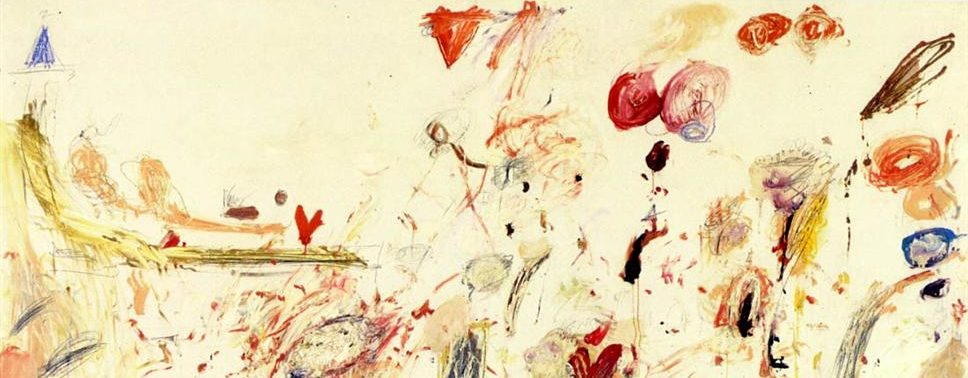

The poem I chose is “Everyone in Me is a Bird”, by Melissa Studdard. To me this poem felt similar to one that we read at the beginning of the year, “Lady Lazarus”, by Sylvia Plath. Both of the poems focus on the internal anguish felt by its narrators. The struggles of both center around the feeling of confinement. In Lady Lazarus, the narrator was trapped by time. In this poem, the narrator feels trapped by her own mind. A final similarity is that both emphasized the narrator’s femininity. In lady Lazarus, the narrator specifically mentions how being a woman has contributed to her anguish, and this work has a similar theme. This is demonstrated with the line, “Mind was a prison, ruby line in its lipstick noir- everything woman.” In class we talked about how the structure of a poem could engender a specific feeling in the reader’s mind. I think this poem is a perfect example of that. The poem is very short. This adds to the intensity of the work, as each words takes on added significance. Furthermore some of the lines create a confusion in the reader, like, “What they said to do, I did not/ but only levitated at the burning”. This confusion is probably analogous to the narrator’s own confusion. We also discussed how imagery affects a poem. In this poem, the imagery reflects the narrator’s internal emotional state. The line “trapped between paper walls” really creates a sense of suffocation. One can understand her pain through this imagery. We also discussed how the visual form of a poem creates meaning. The work’s uniform creates a rigid structure. This rigid structure is exactly what the narrator feels trapped against. Finally, in class we discussed poetry concerning water. This poem also has that theme, with its emphasis on the narrator’s drowning. Like in the other poem, it serves as a symbol for the loss of self.