“By G – I do love the Ingles. G-d dammee, if I don’t love them better than the French by G -!” – Voltaire (qtd. in Buruma 21).

Introduction

Why can’t the rest of the world be just like England? When Voltaire raised this question in 1756 in his Philosophical Dictionary, it would logically follow that his sentiment was ardent nationalism on the part of an Englishman – except that Voltaire was French. This attitude of reverence towards England is particularly illustrative of Anglophilia, defined by Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary as “excessive admiration of or partiality for England or English ways” (44). The concept of Anglophilia has special import for postcolonial literature due to the influence of the English as colonizers. Anglophilia is frequently a theme or source of tension in novels, and characters often exhibit some degree of Anglophilia (see Postcolonial Novel, V.S. Naipaul).

Particular Interests of Anglophiles

While Anglophilia implies an admiration for all things English, specific areas of interest are especially prominent in a study of the phenomenon.

Language: Anglophiles generally regard English as the master of all languages, even if it is not the speaker’s native tongue. The English language is associated with modernity and freedom. “Many people… have been bewitched by it,” notes Ian Buruma in his book, Anglomania (51). This air of mysticism emphasizes learning English and communicating in it. Anglophiles consider it a mark of distinction to be able to speak English, and knowledge of the language is necessary to understanding English literature: “English becomes the sole gateway for accomplishment” (Lockard) (see Languages of South Asia).

English Literature and Shakespeare: While Shakespeare certainly has near-universal appeal, Anglophiles often carry their admiration of the playwright to a higher level of reverence, so much so that Shakespearomania is a subset of Anglophilia. Shakespeare has enjoyed incredible success abroad in countries like Japan and India and the “main legacy of Shakespearomanie was not political, but aesthetic: a taste . . . a mania, and a literary language of incomparable beauty” (Buruma 66). In his travel book England, Nikos Kazantzakis focuses attention on the basic characteristics of England – including Shakespeare – that generate Anglophilia. Admiration for Shakespeare is an obvious expression of Anglophilia as “England sees her face in Shakespeare” and the Collected Works of Shakespeare are frequently accorded as much respect as the Bible (280). This interest in Shakespeare is mirrored by a general interest in English literature. Anglophiles embrace English romances, as well as tomes of science and philosophy, including Newtonian science, British law, Deism, and Freemasonry (Buruma 39).

The Gentleman: “England created the Gentleman,” argues Kazantzakis (171). This man, “who feels himself at ease in the presence of everyone and everything, and who makes everyone and everything else feel at ease in his presence” strikes a balance between passion and discipline that has commanded reverence both at home and abroad (174). In The Western-Educated Man in India, John Useem and Ruth Hill Useem argue that Anglophilia stems from a reverence of four characteristics of the British embodied by the Gentleman, including personal integrity, self-discipline, helpfulness, and thoroughness (142). While these characteristics could theoretically be embraced by a different nationality, Anglophiles tend to consider them distinctly English. Thomas Arnold, a Dutch headmaster of a boys school, once opined that an English Gentleman, “is a finer specimen of human nature than any other country, I believe, could furnish” (qtd. in Buruma 149).

Freedom: Kazantzakis’s exploration of England concludes, finally, that the country’s dedication to freedom has been a primary factor in sparking Anglophilia abroad (279). Many famous European Anglophiles, including Hippolyte Taine, Alexis de Tocqueville, and Giuseppe Mazzini were courted by the idea of freedom (Hitchens). “What attracted Voltaire was England’s political system, its liberty, rationality and sense of fair play,” said Bruce W. Nelan in his review of Anglomania. Many Anglophiles hope that England’s political system can serve as a model for their own native governments, most significantly in the area of liberty.

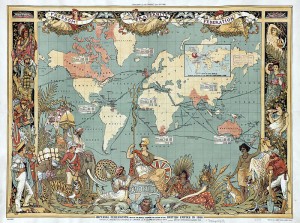

Anglophilia and Colonization

It seems only natural that nations formerly under British colonial rule have a specific interest in Anglophilia and host their fair share of Anglophiles. “Expansion and reaction: the coupling of the two concepts in a complementary pair seems obvious,” J.C. Heesterman says in The Inner Conflict of Tradition. Focusing specific attention on India, Heesterman notes, “Expansion of… British control over the Indian subcontinent there certainly was… But what about its counterpart, the Indian reaction?” (158). Heesterman argues that this reaction often included a blanket acceptance-turned-reverence of British ideals.

Indeed, England was able to promote values, forms of government and basic ways of life in its colonies. Considering the phase of Indian history, “during which the whole country has been brought… under the control or under the direct influence of the British Government, “G.T. Garrett argues that England has had ample opportunity to affect basic colonial attitudes toward England and increase Anglophilia (394). Heesterman notes that, “Western expansion enabled Indian society seriously to attempt… long-standing universalistic ideals that so far had been beyond its grasp” (179).

Education has been a primary avenue through which England has cultivated Anglophilia in its former colonies. Useem’s study of the foreign-educated in underdeveloped countries finds that the purpose of foreign education is “to play an outstanding role in the transfer of Western ideas, methods, and technology” (77). Useem emphasizes that social customs, population pressures and the cultural heritage of a people who have been under foreign rule result in special esteem and prestige for those who have been educated abroad (166). When they return to their native country, the foreign-educated have “a new frame of reference for thinking – not just a new set of beliefs about the Western world” as well as a new population to which these ideas may be transmitted, resulting in Anglophilia (135).

The English language plays an especially important role in the Anglophilia of former colonies. American author Bruce Sterling has noted the effect of the English language on native tongues: “My own native language is English, which is the great, globalized language primarily responsible for crushing all the other languages. English crushes those languages under its feet, like grapes in a global tub,” he said (qtd. in Lockard). In many former colonies, being able to speak English is a badge of honor – it is “the same colonial language accomplishment that it was in the last century” (Lockard). Postcolonial authors frequently write in English instead of their native languages, and English has practically become a necessity as a second language. Often, a preference to speak a language other than English or a refusal to learn English can result in devastating social and political consequences, practically forcing Anglophilia and an appreciation of the English language onto former colonies. This has engendered fierce debate and “a small body of counter-theory has arisen in response to English language domination,” beginning in the 1970s with Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s analysis of the position of English in Africa (Lockard). As Niall Ferguson points out, “The Bard might have said, some are born Anglophiles, some achieve Anglophilia, and some have Anglophilia thrust upon them.”

Examples of Anglophilia in Postcolonial Literature

The presence of Anglophilia in postcolonial nations is reflected in postcolonial literature. Besides being written in English, this literature often illustrates the tension and conflict caused by competing cultures in a country whose history includes domination by England.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

- Chacko tells the twins that they are all Anglophiles – “They were a family of Anglophiles. Pointed in the wrong direction, trapped outside their own history and unable to retrace their steps because their footsteps had been swept away” (51).

- The family reveres Chacko’s English daughter, Sophie Mol, and Baby Kochamma forces the twins to practice their English in anticipation of Sophie Mol’s arrival. “She made them write lines – “impositions” she called them – I will always speak in English, I will always speak in English…. She had made them practice an English car song for the way back” (36).

- Chacko is described as being educated at Oxford and thus “was permitted excesses and eccentricities nobody else was” (38). Mammachi frequently boasts of Chacko’s accomplishments at Oxford, which frustrates Ammu into declaring that, “Going to Oxford didn’t necessarily make a person clever” (54).

- Skin color is frequently referenced. At school, Rahel reads that “The Emperor Babur had a wheatish complexion,” emphasizing his light skin color, and “The Sound of Music” scene excessively mentions the color white, describing “clean white children” (91, 100).

- The children are constantly exposed to English literature. Ammu reads them Shakespeare every night and teaches them the story of Julius Caesar, prompting Estha’s fascination with the phrase, “Et tu, Brute? – then fall, Caesar” and his eventual use of it to torment Kochu Maria who is convinced he is insulting her in English (80). Roy references Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in her description of the History House, and the twins read Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book (51).

- English culture is embraced with the family’s preoccupation with “The Sound of Music,” where the twins “knew all the songs” (35).

Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga

- Babamukuru has spent five years in England, which gives him special prestige in the family unit. “I was only five when Babamukuru went to England. Consequently, all I can remember about the circumstances surrounding his going is that everybody was very excited and very impressed by the event,” Tambu says (13). In fact, Babamukuru was offered the scholarship to study in England so that he and Maiguru could “be trained to become useful to their people” (14).

- Babamukuru’s English education also earns him great respect. ” Nhamo was very impressed by the sheer amount of education that was possible. He told me that the kind of education Babamukuru had gone to get must have been a very important sort to make him go all that way for it” (15).

- Babamukuru’s English habits and clothing make him resemble the Gentleman – “In his mission clothes he was a dignified figure and that was how I liked to imagine him” (8).

- Babamukuru’s children are torn between their African heritage and English culture. When Nyasha and Chido return, they’re dressed in English fashion (37). Later, Maiguru explains that her children picked up their ways in England (74).

- Language is also a large issue for Nyasha and Chido. When they return to the homestead, Maiguru notes that, “They don’t understand Shona very well anymore. They have been speaking nothing but English for so long, that most of their Shona has gone” (42).

- Babamukuru’s home illustrates a preference for all things English. The family eats with English utensils, uses English novelties like a tea strainer, and prefers English food (48; 72; 82).

Works Consulted

- “Anglophilia.” Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary. 1977.

- Buruma, Ian. Anglomania. New York: Random House,1998.

- Dangarembga, Tsitsi. Nervous Conditions. Seattle: Seal Press, 1988.

- Garratt, G.T. “Indo-British Civilization.” The Legacy of India. Ed. G.T. Garratt. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938.

- Heesterman, J.C. The Inner Conflict of Tradition: Essays in Indian Ritual, Kingship, and Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Kazantzakis, Nikos. England. Oxford: Cassirer, 1965.

- Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. New York: Harper Perennial, 1997.

- Useem, John, and Ruth Hill Useem. The Western-Educated Man in India: A Study of his Social Roles and Influence. New York: The Dryden Press, 1955.

- Voltaire. Philosophical Dictionary. Transl. Theodore Besterman. New York: Penguin Books, 1972.

Author: Elizabeth Barchas, Fall 2000

Last edited: October 2017