Overview

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) was the official United States policy on military service by gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. The policy was a compromise that aimed to address the issue of homosexuality in the military while avoiding the outright ban on gay service members that had previously existed. This wiki entry will explore the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy, primarily exploring how it affected LGBTQ military personnel.

| History |

| Examples |

| > Challengers of the Policy |

| > Queer Identity |

| > Discharges |

| Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Visuals |

| Works Cited |

History

The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy was implemented in the United States in response to political and societal debates over LGBT people serving openly in the military. Prior to DADT, there were specific restrictions prohibiting gay people from serving in the United States military. Homosexuality was deemed incompatible with military service, and service men discovered to be gay faced discharge. For instance, “during the 1980s the military branches discharged close to 17,000 men and women under the homosexual category”(Pruitt). As a result of these restrictions, the military experienced harsh criticism, prompting the development of the DADT policy during the early years of the Clinton administration. President Bill Clinton, who campaigned on a promise to allow gay people to serve openly in the military, faced stiff opposition from both military commanders and conservative members of Congress. In response to this criticism, President Clinton and Congress negotiated an agreement in 1993. To handle the issue of homosexuality in the military, DADT was implemented as a compromise policy. As part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994, the policy was officially implemented as a federal law. The DADT essentially meant that military authorities were not allowed to inquire about a service member’s sexual orientation. Service members were not required to disclose their sexual orientation, but they could not openly declare that they were gay. However, if a service member’s sexual orientation was discovered, they could be subject to discharge, unless they remained celibate and did not engage in homosexual conduct.

The DADT was fraught with controversy from the start. Critics said that it resulted in discrimination and the removal of qualified employees based on their sexual orientation. For many years, there were many legal and social challenges to the policy, which brought more negative than positive attention to the policy. As a result, after many years of debate and disagreements, Congress enacted the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act in December 2010, paving the path for the official repeal of DADT (Pruitt). On September 20, 2011, the policy was officially lifted, allowing gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals to serve openly in the United States military (Pruitt). The repeal of DADT was viewed as an important step forward in the ongoing fight for LGBTQ+ rights in the United States, and was considered as a step toward greater inclusivity and equal treatment for all service members, regardless of sexual orientation.

Examples

Challengers of the DADT

From the moment the DADT policy was enacted, it sparked outrage from a variety of groups, but the majority of those who opposed it were LGBTQ+ advocates. The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy was widely opposed by LGBTQ+ advocates, who actively contested it as discriminatory and damaging to LGBTQ+ service personnel. In practice, the policy was intended to safeguard lesbian, gay, and bisexual military personnel from discharge by allowing them to conceal their sexual orientation.However, it was not much different from the military’s earlier regulatory restriction in that if the individual’s sexual orientation was revealed, they would be discharged. According to Dixon Osburn, “you were being discharged for saying you were gay or for engaging in sexual behavior with someone of the same gender or if you married or intended to marry someone of the same gender. So the bans were exactly the same (De la Garza).” As a result, advocates contended that DADT perpetuated discrimination by requiring LGBTQ+ military personnel to conceal their sexual orientation, effectively forcing them to live in secrecy. They also claimed that the DADT put LGBTQ+ service members at risk of being outed against their will, perhaps leading to discharge from the military. This was perceived as an intrusion into their privacy. Overall, LGBTQ+ advocates considered the policy as discriminatory, damaging, and incompatible with equality and non-discrimination principles. Their efforts, combined with shifting public attitudes and backing from some military commanders, aided in the repeal of DADT in 2011.

Queer Identity

The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy had a significant impact on queer identity in the military. It forced LGBTQ+ service personnel to conceal their sexual orientation, effectively preventing them from expressing their true selves. As a result of this suppression of identity, a culture of fear, secrecy, and discrimination arose. LGBTQ+ service members were compelled to live a double life, unable to openly acknowledge their partnerships or attend LGBTQ+ community gatherings.The policy hindered the personal development and mental well-being of queer service members as “decades of research in health and social psychology revealed that sexual orientation concealment resulted in serious long-term health risks associated with minority group stress” (Johnson 109). According to Brad Johnson’s research, this policy imposed a major psychological and emotional strain on the military, producing stress and anxiety and impeding the creation of a robust, supportive LGBTQ+ community (109). DADT effectively stigmatized LGBTQ+ identities, repressed self-expression, and reinforced a discriminatory culture, making it difficult for LGBTQ+ service members to fully embrace and integrate their identities while serving their country.

“A lot of the reason that I got out was looking down the road and seeing that I was always going to have to hide this part of myself.”

Rogin, Ali. How Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell has affected LGBTQ service members, 10 years after repeal.” PBS, Dec. 2020, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-dont-ask-dont-tell-has-affected-lgbtq-service-members-10-years-after-repeal

Discharges

The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy resulted in an increase in the number of queer military personnel discharged by institutionalizing a framework that deliberately attempted to identify and remove LGBTQ+ service members. Service members were discouraged from openly declaring their sexual orientation under DADT. If their orientation was found through any means, including anonymous tips, investigations, or personal declarations, it frequently resulted in a discharge procedure. According to Jared Odessky, “advocates estimate that, between World War II and DADT’s repeal in 2011, the military discharged as many as 114,000 service members on the basis of actual or perceived sexual orientation, sweeping in transgender, gender non-conforming, and queer service members perceived to be gay as well.” The policy essentially forced LGBTQ+ members to live in fear of their true identities being disclosed, creating a climate of mistrust and secrecy. For example, if a gay service member confided in a close friend about their sexual orientation and that person later exposed this knowledge, it may result in an investigation and dismissal. As such, there have been multiple documented incidents of military members being dismissed under DADT after being outed by another person or accidentally revealing their sexual orientation. Hence, as a result of DADT, thousands of skilled and dedicated LGBTQ+ service members were forced to leave the military, depriving the military of significant talent and creating immense emotional anguish for those discharged.

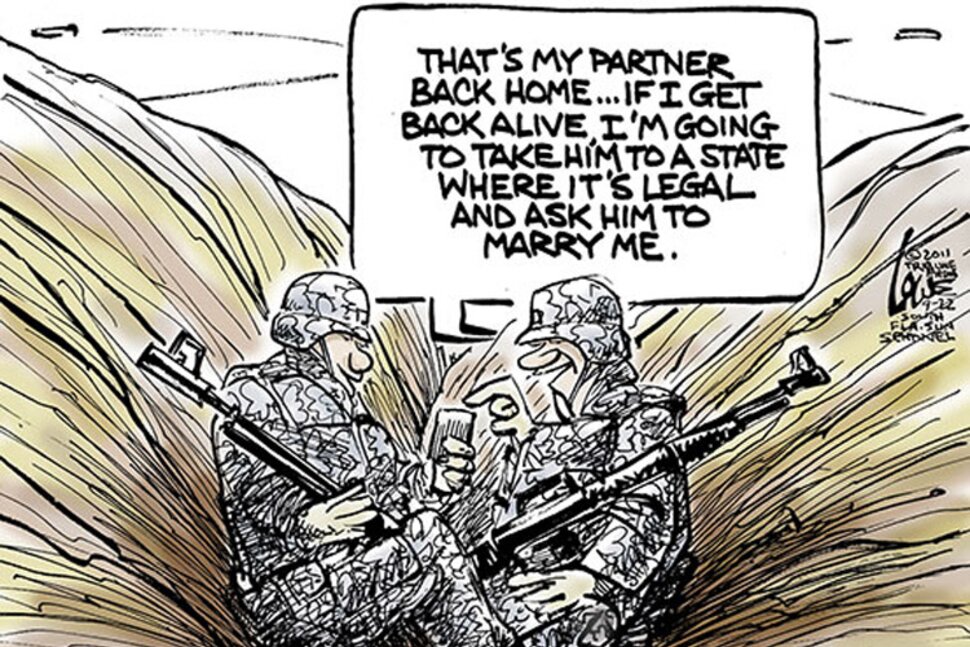

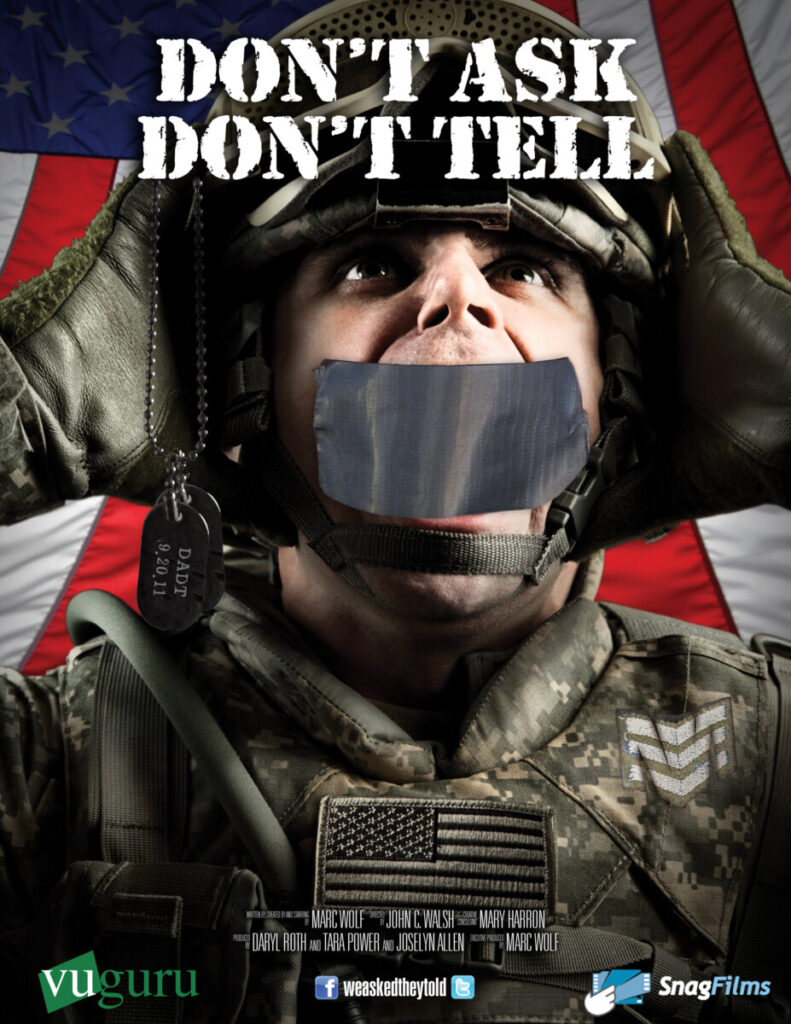

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Visuals

The reality of the DADT through images.

Works Cited

Burks, Derek J. “Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Victimization in the Military: An Unintended Consequence of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’?” American Psychologist, vol. 66, no. 7, Oct. 2011, pp. 604–13. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.proxy.library.emory.edu/10.1037/a0024609.

De la Garza, Alejandro. “’Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Was a Complicated Turning Point for Gay Rights. 25 Years Later, Many of the Same Issues Remain.” Time, July 2018, https://time.com/5339634/dont-ask-dont-tell-25-year-anniversary/

Human Rights Campaign. “Repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Human Rights Campaign, https://www.hrc.org/our-work/stories/repeal-of-dont-ask-dont-tell

Johnson, W.Brad, et al. “After ‘Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’: Competent Care of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Military Personnel during the DoD Policy Transition.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, vol. 46, no. 2, Apr. 2015, pp. 107–15. EBSCOhost,

https://doi-org.proxy.library.emory.edu/10.1037/a0033051.

Odessky, Jared. “LGBTQ+ Veterans Still Suffer Harms From “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Ten Years After Repeal.” Legal Aid at Work, Aug. 2021, https://legalaidatwork.org/lgbtq-veterans-still-suffer-harms-from-dont-ask-dont-tell-ten-years-after-repeal/

Pruitt, Sarah. “Once Banned, Then Silenced: How Clinton’s ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ Policy Affected LGBTQ Military.” History, Apr. 2018,

https://www.history.com/news/dont-ask-dont-tell-repeal-compromise

Rogin, Ali. How Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell has affected LGBTQ service members, 10 years after repeal.” PBS, Dec. 2020, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-dont-ask-dont-tell-has-affected-lgbtq-service-members-10-years-after-repeal