Margarethe Conner Final Project – December 14, 2022

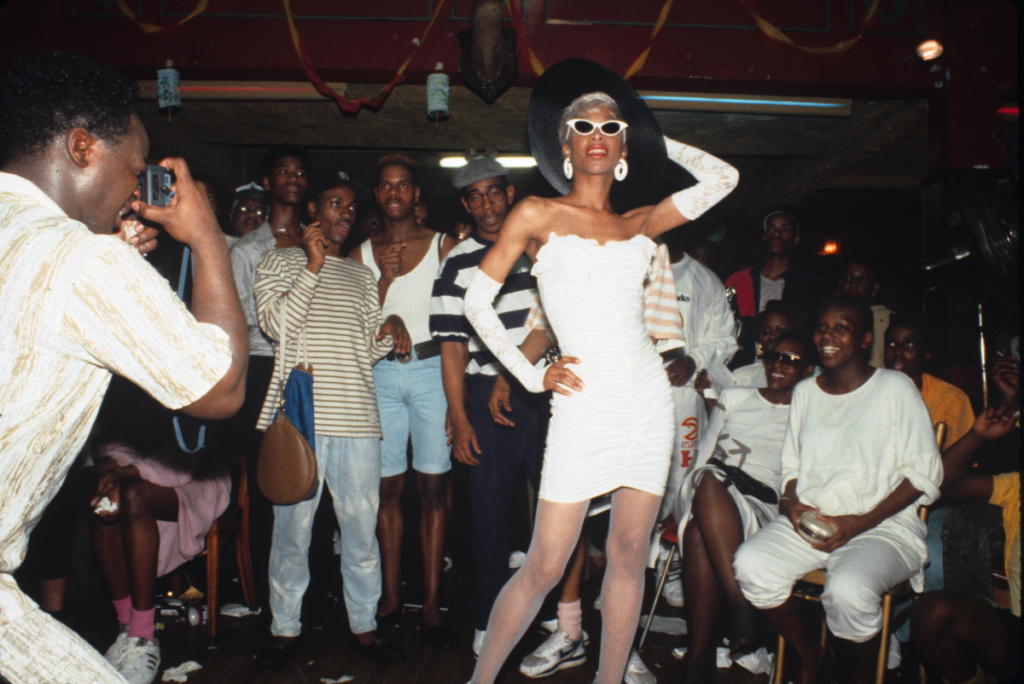

What comes to mind when you hear the term “ballroom culture”? You might think of gowns and waltzes. You also might think of the Netflix show Baby Ballroom. Or, you could think of FX’s Pose, or RuPaul’s Drag Race. The latter is what I’ll be focusing on for the purposes of this article. Ballroom culture describes the culture surrounding the drag shows that majority Black and brown queer people participated in in New York City beginning in the 1970s and 80s and continuing on today.

A version of balls has been around for centuries. From 1867-1869, Hamilton Lodge No. 710, a club for well off African-Americans, threw a charity masquerade gala called the Annual Odd Fellows Ball. This event featured men in female drag and women in male drag, and awards were given out for “the most perfect feminine body displayed by an impersonator”. These events were predominantly for Black people but some white people did attend.

Balls like these continued to be thrown throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, however they were mainly called Masquerade and Civic balls. Although these events were a space for queer people to express themselves, they were not removed from the prejudices of society.

Photo by Aaron Siskind from the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Harlem nightclub dancers (1937)

By the 1920s when they became more public, these events were called F****t Balls after people realized that queer people were the majority of the attendees. Additionally, predominantly white men put on these balls, and if Black people wanted to have a chance of being scored well they were expected to lighten their faces, as most of the judges were white until the ’60s. Eventually, Black and brown people became frustrated with being scored unfairly so they split off and began throwing their own balls. This was the start of the ballroom culture that is recognized today.

Central to an understanding of ballroom culture is the idea of belonging. Many of the people participating in balls especially in the ‘70s and ‘80s had been rejected in one way or another. Most of them were Black or brown and faced racism in society, and many had been thrown out of the house by their families for being queer, or had run away. They were of a low socio-economic status, and some lived and worked on the streets. Ballroom culture provided these people with a sense of belonging in many ways.

First, many people who walked in balls were part of a house that they competed on behalf of. These houses were headed by “Mothers”, who were often trans women (Femme Queens), or gay men in drag. People in the same house formed a chosen family that provided a sense of belonging that they didn’t get from society. They figuratively fought for each other by walking or voguing in balls, and a win for one member of a house was a win for all of them.

Balls also created a sense of belonging through the celebration of gender fluidity. Ballroom culture held onto traditional definitions of sexuality and gender, but they saw those identities as malleable. People could dress as a gender they didn’t identify with, or they could express themselves as the gender they did identify with that they weren’t assigned at birth. Many trans women in the ballroom community wouldn’t go out in public dressed as a woman, but in balls they were celebrated for presenting in the way they most identified with.

While ballroom culture has done so much good for queer and trans people, its acceptance by mainstream media has been gradual. In 1990, two key forms of media came out that exposed ballroom culture to the world. In May, Madonna’s song “Vogue” came out. This song was Madonna’s biggest hit at the time, and was the best selling single of the year. It is rumored that Madonna was at the Love Ball AIDS Fundraiser in 1989 when she got inspiration for the song, however other accounts say she witnessed voguing at a club. The music video featured men voguing, which was a dance originated by the people who performed in balls. The video was choreographed by two members of the ballroom community Jose Gutierez Xtravaganza and Luis Xtravaganza, both of whom were also in the video.

Following the release of the song, there was a lot of enthusiasm within the ballroom community that they were on their way to being accepted in the mainstream media, however others worried that Madonna’s name might overshadow the history of voguing and ballroom culture. Additionally, Madonna as a white woman profiting off of a dance originated by predominantly poor queer people of color upset many people.

In August of 1990, only three months after the release of Madonna’s “Vogue”, the documentary Paris is Burning was released. This documentary followed several members of the ballroom community in New York City in the late ‘80s, and documented their struggles with sex work and discrimination as well as the joy and community they found within the ballroom world.

While it was mostly well received at the time, author and activist bell hooks critiqued the film in her piece “Is Paris Burning?”, calling it a “spectacle for white people”. She described going to a screening and hearing the predominantly white audience laughing at the trauma of the people in the film; they didn’t see what hooks saw, which was a group of marginalized people performing whiteness – the very identity that oppressed them. Additionally, hooks took issue with the families of the featured people not being included, and accused the director, Jennie Livingston, of not depicting the main cast as complete individuals. Additionally, Livingston was a white lesbian and not a member of the ballroom community herself, which garnered some criticism. Both “Vogue” and Paris is Burning were created by white outsiders to ballroom culture and arguably don’t capture its complexity, however they did expose ballroom culture to the world in a way that hadn’t been done on a large scale up to that point.

Unless you’ve been completely avoiding pop culture for the past 10 years, you’ve heard of RuPaul’s Drag Race. This is a reality competition show for drag queens that premiered on February 2, 2009 and has had 11 seasons and 3 spinoffs since then. RuPaul had been a superstar in ballroom culture since the ‘90s, when his single “Supermodel (You Better Work)” came out, however Drag Race thrust him and ballroom culture into the spotlight.

The show showcases the art form of drag, but also depicts how the queer community is often alienated from their families and experiences shared traumas through conversations between contestants on the show. The format of a reality show allows for these authentic moments to be revealed to the world, and gives viewers a chance to hear from members of the community themselves about their experiences with drag and the ballroom world, as well as navigating their queerness. This differs from Madonna’s “Vogue” and Livingston’s Paris is Burning because trans and queer people and drag queens are able to tell their own stories instead of having them filtered through the lens of someone else.

While there are many notable series to mention that focus on ballroom culture, perhaps the most popular has been FX’s Pose. Pose takes place in 1987 and focuses on several trans women and queer men who are members of a house in New York City.

The show dives into the dangers and struggles of members of the queer community during this time period, focusing on HIV, unemployment, and sex work. It also shows the joy of the community and family that queer people found within ballroom culture. Pose is especially notable because all trans characters are played by trans actors. Additionally, Janet Mock, a trans woman, is a writer, director, and executive producer on the show. Many prior movies and TV shows about trans people had featured cis actors playing trans people, and Pose revealed the importance of authentic representation on and off screen. This is also something that the main cast of actors have been very outspoken about, and they’ve used the platform that Pose has given them to advocate for authentic representation of trans people, and specifically trans people of color.

From Madonna to Pose, representation of ballroom culture in the media has proven to be essential to the acceptance and understanding of this rich history and community. These pieces of media have also started conversations about who should be entrusted to tell the stories of marginalized groups. Can someone who’s not a member of the group sufficiently understand the experience of those who are, and enough to share that experience with the world? Does the authenticity of the work suffer? When comparing “Vogue” and Paris is Burning to RuPaul’s Drag Race and Pose, I would argue that having trans people and members of the ballroom community tell their own stories not only leads to more accurate representation, but also provides a platform for these people to advocate for other trans people. This is not to discount what “Vogue” and Paris is Burning did to shine a light on ballroom culture and provide an opening for better representation in later media. However, moving forward we can look to shows such as Drag Race and Pose as examples when advocating for authentic representation of marginalized communities.