by Timothy Elofsen

The large figure stood before me, sitting at the other side of the table. His arms crossed, his body posture closed, he regarded me in frustration. Just beyond him, the television droned on, the reporter on the news listing off facts about a developing news story. It was late May. George Floyd, a black man. Killed by police.

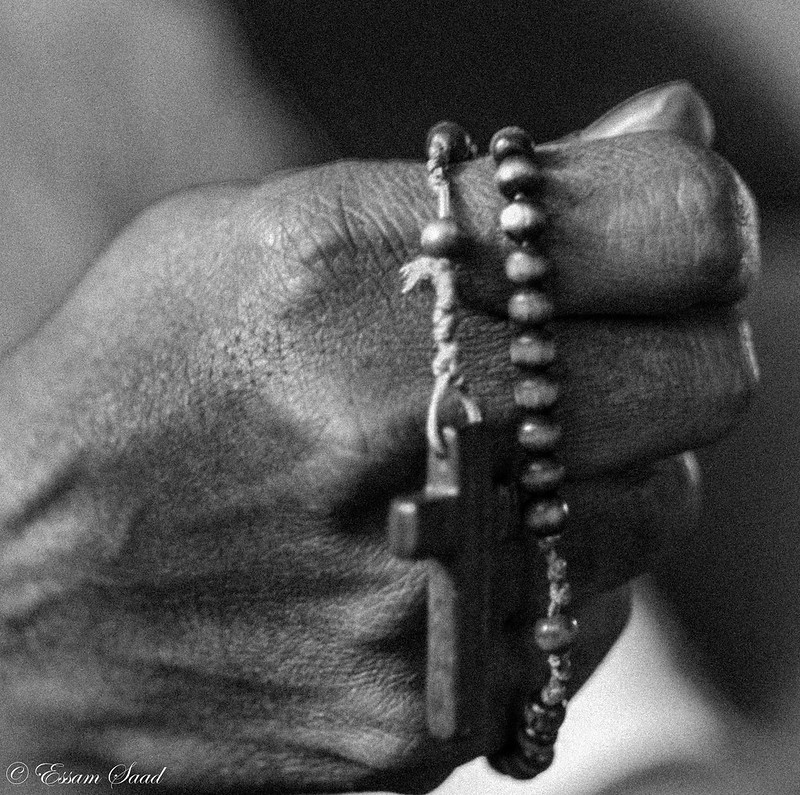

Eight minutes and forty-six seconds.

Another month.

Another name.

Another crime gone unpunished.

There’s a cold logic to the sentiment expressed by a tyrant of the twentieth century who expressed that one death is a tragedy. A million or so is a mere statistic.

As facts rolled in from the news channel, I could only think of many of my friends who were persons of color, who were grieving the wrongful death of Breonna Taylor just over a month prior as well as countless others who had died at the hands of police. The terror. The anger. The numbness. The hopelessness of a cycle that just wouldn’t stop.

The person standing opposite me had walked in and listened for a moment before shaking his head and mentioning how it was a shame that another person had died, if only he had listened to the officers in the first place, kicking off a conversation about racism and sin. We had quickly come to an impasse, characterized by a comment of his rooted in his rejection of any concept of corporate or institutional sin.

I have said this once and I will say it again—I will not be saddled down by sin which is not my own! And I will not own that sin which I have not committed!

In his mind, unless the police were made up of persons all committing racist acts, they couldn’t be condemned as such in the first place.

For many Americans, such tensions are not new. Speaking as a straight, white, middle-class male from New England, however, my privilege in life had afforded me the option of not engaging in these conversations because my identity as a person was not being targeted and profiled. And I recognize my inadequacy in speaking about such matters, too. I know that my friends do not owe me any explanations for their reactions to another day in the United States and I can try and figure out what I – and others interested in the task of bridging the theology of the church and academy with that of the public sphere – in trying to figure out what a way forward might look like in light of these horrific travesties.

As a white person speaking to primarily other white people within the church, I confess that we have been conditioned to think about sin as primarily an individualistic thing, as we sit atop a system designed for us in mind which does not actively seek to do violence against us for the sake of another. We have separated and siloed ourselves enough that we do not see the impacts of such systems upon others. Therefore, we need the voices of others to help us see that which we have lost vocabulary for in our own traditions – that is, both the need of and the implementation of repentance and lament in light of systemic injustice.

As persons interested in preserving the lives of those around us as also bearing the image of God, when statistics arise which point out that statistically, persons of color stand a much higher chance of dying at the hands of a police officer, we must find a new lens through which to examine the world and diagnose it accordingly.[1]

Practical theologian Lauren Winner describes the difference of repentance (something most Christians are familiar with) and lament (something most white Christians are not) by describing it as such:

Repentance involves recognizing discrete responsibility, and it is limited to the things for which I am responsible… Lament, by contrast, expands to include the damages of the cosmos for which I am not remotely responsible–the sinfulness of the world, the brokenness that we are born into and inherit, the principalities and powers by which we are trapped.[2]

For many persons of color, both who identify as Christian and those who do not, the process of lament comes for the purpose of indicting the structures and systems that be as wrong, attempting to then point toward a more hopeful, life-affirming future for all. M. Shawn Copeland argues that such forms of lament are evident within movements like #BlackLivesMatter and reminds us first of “of our intimate and irrevocable relatedness to all creatures in the here-and-now through His name” over and against the temptation of systems of power which encourage us to “conspire to not remember; we choose to forget. We repress and erase; we edit and delete. The result is a peculiar and unsettling, even puerile, ignorance that seeks to pass as political innocence.”[3] Nothing of significance gets changed as those in power and/or with privilege decline to accept responsibility and shrug it off as an unfortunate unchangeable reality.

Learning the validity and necessity of lament within the Christian religious imagination rejects such lines of thinking. Lament, as Anne Wimberly states at the start of her anthology on moving from lament into meaningful change, “[comes] to grips with woundedness, grief, and lament in ways that release and move to declare why it is important to live, to engage in advocacy, and to demand change.”[4] This is done through acts of resistance, acts which reject bids to forget and move on, acts like remembering Breonna Taylor’s name in the sea of headlines screaming for all of our attention.[5] Through it, communities are allowed to grieve and process through pain all while seeking the steps necessary to critique and reform the situations, persons, and systems which contributed to the injustice.

While millions may simply be a statistic, lament rehumanizes those whose voices have been stifled, still demanding justice.

Again, as a person who has enjoyed many privileges within American society, while I cannot begin to imagine what daily life is for my peers, perhaps one of the best paths forward is through cultivating spaces for lament in your own life, in your community, and in the circles in which you find yourself. Copeland concludes that it is only through listening to the

’beautiful impatience’ of the women and men and children who are the faces and bodies of BlackLivesMatters teaches us all what authentic human being means… working out in their bodies a new agenda of critical attentiveness and analysis, of risky solidarity and active engagement to create a just and renewed future for us all.”[6]

In order for this to be done, we need to examine not just the individual acts of people, but the setting as well. If we believe that sin has tainted creation, we should cultivate more of an awareness of how deep this infection goes. For anyone serious about looking for where Christ is at work today, looking and listening to the voices of our neighbors would be a good place to start.

QUESTIONS:

- What do you think is the relationship between lament and recognizing corporate OR systemic sin? Repentance and individual sin?

- How can you actively make space for lament in your own life?

[1] Frank Edwards, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito, “Risk of Being Killed by Police Use of Force in the United States by Age, Race–Ethnicity, and Sex,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 34 (August 20, 2019): 16793–98. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821204116.

[2] Lauren E. Winner, The Dangers of Christian Practice: On Wayward Gifts, Characteristic Damage, and Sin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 158.

[3] M. Shawn Copeland, “Memory, #BlackLivesMatter, and Theologians.” Political Theology, February 11, 2016, 160211234944003. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462317X.2016.1134137.

[4] Anne E. Streaty Wimberly, “Religious Education and Lament: Inviting Cries from the Heart, Guiding the Way Forward” in From Lament to Advocacy: Black Religious Education and Public Ministry, (Nashville, TN: Wesley’s Foundery Books, 2020), 3.

[5] Dylan Lovan, “3rd Breonna Taylor Grand Juror: Cops ‘Got Slap on the Wrist,’” The Associated Press. November 16, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/breonna-taylor-louisville-shootings-005f99347b202b3add4baca340a54820.

[6] Copeland, “Memory.”

1 Comment

Add Yours →Timothy, thanks for your honesty and careful theological reflection. I have two questions in response: (1) Is it possible that, without asking people experiencing oppression to “explain” it to us, that by listening to their lament the hearts of others are “pricked,” an invitation to moral consciousness and perhaps repentance on the part of those who benefit from oppressive systems? And (2) What about being white, or white-cis-het-male, might be worth lamenting? Here, I am thinking about the constraining effects of both white supremacist thinking as well as “toxic masculinity.” Freire would argue that these ideologies are repressive even to those who ostensibly “benefit” from them and, in your language, lamentable.