by Jo Ann Batteiger

“Are you ready, Joannie Bananie?” My dad asked me, with a mischievous look on his face.

I sprang up from the couch, still in my pajamas and slippers. We had gathered around to watch the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. I rushed up the steps and pulled out the step stool, and dragged it over to the bookshelf in the kitchen. Tall books, short books, spiral bound booklets made by the ladies at church, a couple of magazines. I still couldn’t find it. I looked over to where we kept our phonebooks and the church directory, and there it was smack in the middle of the shelf. The second most sacred book in our household after the Bible: The Better Homes and Garden 75th Anniversary Cookbook.

Gifted to my dad the Christmas prior, we had a lot of fun playing around and experimenting with the different recipes that were contained in the book. But this day was no day for jokes. We had to focus. Our task was simple and clear: make the rolls for Thanksgiving dinner.

I flipped through the book, my fingers brushing the stains of memories of meals from the past year to find the recipe. I pulled down the ingredients, checking the book often to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything: flour, sugar, milk, butter, eggs, yeast. When my dad finally joined me, it was time for us to get rolling. He pulled out the ceramic mixing bowl that had belonged to his mom before she passed. The bowl was one of its kind— likely handmade by either my grandmother or one of her friends, and in it, so many recipes came to life. Brownies, homemade doughnuts, chocolate chip cookies. This bowl is more than just a kitchen gadget, it is a means by which my dad is able to stay connected to his mom, and a way for me to stay connected to my grandmother since she had died when I was so young.

Into the bowl, this artifact, this unusual means of grace, went the flour. In a separate bowl, we activated the yeast. It was in watching the yeast come to life that my dad taught me science— if the water is too warm the yeast will be killed. If the water is too cold, the yeast wouldn’t t fully activate. The water has to be just the right temperature in order to work the way that it needs to. While the yeast was activating, we pulled out the saucepan and heated the milk, sugar, and butter together just until it was very warm to the touch. Like the yeast, this had to be done just right, otherwise it would prove disastrous in the end. I was beginning to realize that while this task was of utmost importance, it was also become farther and farther from the simplicity I had envisioned.

Once the separate mixtures had achieved their respective equilibriums, they were thrown together in the ceramic mixing bowl and mixed together, forcing a new balance to be created as a new mixture was emerging from the three former ones. The dough started to form. In the bowl, the sides were scraped and the remnants were folded in, and out onto the floured counter the dough went. My dad tore off a piece of the dough and showed me how to knead.

“So what you want to do is take the bottom part of your hand, and turn and fold. Turn and fold. Turn and fold. There you go, kiddo, you got it,” he said.

I, with my smaller portion, and my dad with the larger portion fell into our rhythm. Turn and fold, turn and fold. When the dough had become sufficiently elastic, it was time for it to rest. Back into the bowl the dough mixture went, covered with a dish towel and tucked in for a two-hours long winter’s nap; it was time for us to rest, too.

Two hours had passed. And in one swift punch, the very tall and very expanded ball of dough that we had spent so much time on, making sure everything was just right, collapsed before our eyes. From there we took smaller pieces of dough forming them into roll shaped balls, and placed them on the baking sheet. Letting them rest for just a little while longer to rise some more, they then went into the oven. It wasn’t long until we would start to smell the yeasty goodness.

My dad guarded the oven with his life, ensuring that no one would open the oven door until the timer went off, lest we interrupt the balance that the baking process was finalizing. The timer dinged obnoxiously, but we didn’t seem to mind too much. We knew that this ding was alerting us that the best part of Thanksgiving was coming: homemade rolls.

As we set the table and as dishes made their way from the kitchen to the dining room, the rolls smelled heavenly. My brother thought so too, as he always made a point to look and see and smell what was going on before it landed on the table. When we sat down together for our meal, it was incredible to see the things that my dad and I had made from scratch, with our own literal hands, in front of us, ready to eat and give thanks.

This was not the last time we made these rolls. Every Thanksgiving and Christmas since then, and still today, the rolls have made their way onto our dinner table, even now as my family lives across two times zones and in three different states. The recipe has certainly been adapted as my dad continues to experiment with the science in the baking to find the right balance in the density of the bread. He scribbles notes in our second sacred text, crossing out the things that didn’t work, circling the things that do.

For my dad and my family, cooking and baking is an act of love and care. Many of my memories growing up revolved around family dinners or learning how to cook with both my mom and my dad in the kitchen. From a young age, my dad always had the step stool ready to go so that I could watch him make brownies, hoping that I would get to lick the spoon covered in brownie batter once the brownies went into the oven.

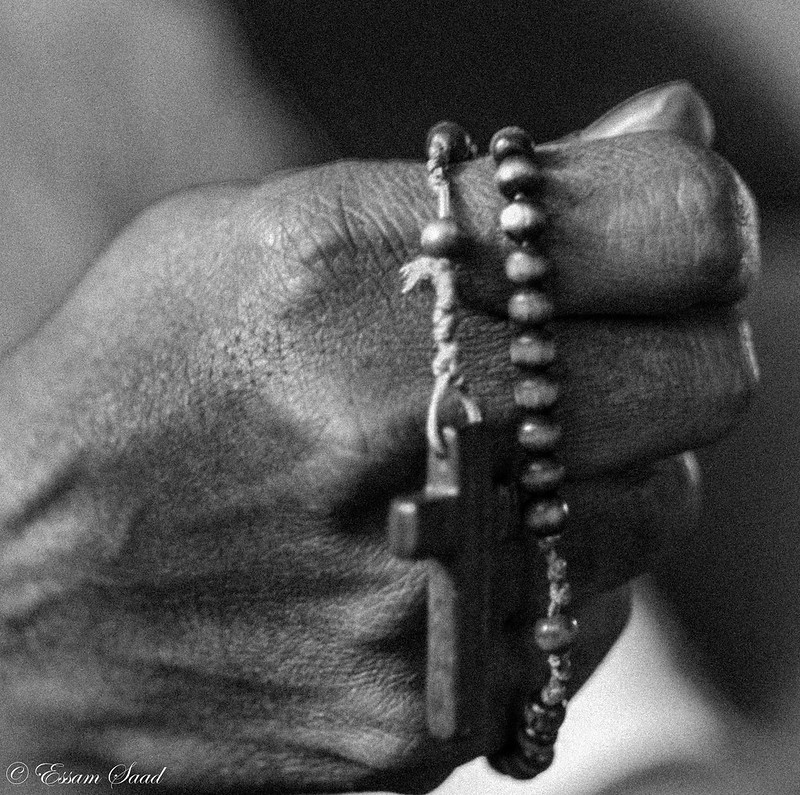

It is the act of cooking and the sharing of meals together that is very sacramental for my family. It is a way of remembering those who have gone before by creating the recipes that had been handed down to us. Or in using their ceramic mixing bowl as a way of bringing the past into the present in an unusual liminal space of mixing flour, yeast, milk, butter, and sugar that brings forth a new concoction that is far better than the ingredients solely on their own. It is our way of experiencing means of grace in the creating and consuming of a fresh, warm, homemade roll.

It is in the practices of slowing down, paying careful attention, turning and folding, that invite us to slow down and enter into our memories and remember the other times when things were crumbling beneath our feet that remind and ground us that we have already gotten through all of our hardest days so far.

This year has been extremely difficult and challenging in so many ways that are already coming to mind as you read this. Everything that we once knew or held dear has been uprooted and unsettle. While we have adapted to this being our new normal, I think we just need to acknowledge that this is not normal. This is not the way things are, nor the way that they should be. This unprecedented time, this unusual season, this whatever it is you choose to label it has forced us to address the fact that our rate of productivity and work and efficiency is one on of the quitter things that has subtly been eating away at our personhoods for a long time. We have internalized this idea and ethos that if we work at our maximum capacity every day, we will be rewarded with a bonus, with perks at work, with some sort of reward that will move us up the invisible ladder. Very quickly, our success becomes intertwined with our self-worth. That we can achieve or earn the love we so desperately crave and need. When I earn this next position, or this grade, or the game, I will be worthy of love.

But, at what cost? Our humanity? Our mental and emotionally well-being? Our care for others over ourselves? Forgetting our own internal self-worth and knowledge that we are already good enough because the God who has loved us and continues to love us into being has told us that from the very beginning of time?

When I think about the practice of slowing down and paying careful attention to my roll recipe, I am reminded of these things that are true about myself. That even as I am slowing down and resting, there is still transformation happening within me. The act of slowing down and paying careful attention is not just a literal thing that happens so that our recipe turns out right, it is also counters the ongoing narrative in our culture and society. In a world that is constantly on the go and trying to attain the next big thing, to slow down and pay careful attention is a subversive act. Many stories throughout the Old and New Testament emphasize these themes. People move too fast for their own good and are reminded through various means to slow down and pay careful attention to who benefits from the fast-paced biblical world and who is left out. Out of the chaos, God calls us forth into new life; to not continue cycles of harm to ourselves or others any longer. We are reminded through these ancient stories and the trials and tribulations of our biblical ancestors, that each of us are God’s beloved, carefully knitted in the womb, and loved exactly as we are.

In our attempt to keep up with the continuous race of life that demands so much from us to decide our careers or callings so that we might get started and get ahead to get the best opportunities, it is so easy for us to lose sight of our own belovedness and our shared humanity with each other. Patrick Reyes in his book, Nobody Cries When We Die, talks about how the question around what our Purpose in Life ™ should be is a faulty starting point. To fully understand what we are supposed to do, we have to first ask the question of who do we want to be? His way of understanding this is asking the very basic questions of “How am I using this living breathing body? or How does the way that I am living reflect a certain call to live and breathe?” (Reyes, 14). Reyes goes on to argue that for communities that are marginalized, the first call for vocation is about survival and asking the question of how do I make sure that I am living my life in a way so that I can survive to see the next day?

This year has forced us all into survival mode, with communities still being more disproportionately affected than others. Now, more than ever, to slow down and pay attention, and to deeply pay attention to who is at the table, who owns the table, who is creating the table, and who is missing from the table is vital to our communal survival. I am not here to slap a feel-good platitude on the year 2020, when it has truly been just awful and chaotic and deeply unsettling for so many reasons. I do think; however, we are at a pivotal moment in our shared human story where we can choose the path ahead in light of what we have learned and what we know. We can choose to be grounded in practices that sustain and ground us, like making rolls, or being outside that force our bodies to slow down and pay attention to the world around us. We have a deeper social awareness that invites us to reflect on how we are using our physical bodies to reflect the way we are choosing to live and breathe that is consistent with our internal truths, grounded in our God-given belovedness.

I wish I could tell you that this will all be over soon, and things will return to normal, and we can move on from this mess, but the truth is that in my experience, and maybe in yours, that things never go back to the way they once were. Even if they try to, it doesn’t feel right. To go back to normal and forget this whole mess dismisses the pain and suffering that so many people have gone through. Why would I want to go back to a normal that ignores the pain and cries of my neighbors? Isn’t that a big part of the reason why we have gotten to where we are in the world in the first place? I want to move forward in a world that slows down and pays careful attention to the people who are in pain and suffering. I want to move forward in a world that honors the belovedness of all of God’s people and creation. I want to move forward in a world that invites forth a call to live and breathe a little differently than what we have known. I will move forward in this world as it is now, practicing slowing down and paying deeper attention to myself, to others, and to the world. For it is in these spaces of rest and slowing down and paying attention that the transforming work that happens under the dish towel allows us to rise and be a new creation with God and with each other.

4 Comments

Add Yours →Wow. You are a beautiful writer. Loved this piece. Spoke to my soul as I struggle daily with learning to slow down and teach my children and husband to do the same. And I adore baking so what a delight to read this. I’m going to print this out and read it slowly again through the holiday. Thank you!!

Angela, thank you so much for your kind words. Blessings to you and your family in this unusual Advent and Christmas season!

I love your story and am also thinking of how punching down bread feels especially fitting as well. Baking bread is one of my own favorite sacred practices and a beautiful metaphor. Hope you have a lovely holiday!

Thank you, Jo Ann. As I read, the word that kept coming to me was “lingering.” I think you have a theology of lingering, here. It’s not just being present in the instagram-worthy moments of baking (but dang, those rolls are gorgeous) or nature, but also being present to suffering, refusing to rush past it. Thank you!