By Sarah Quigley, Project Archivist for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, MARBL

“Working for Freedom: Documenting Civil Rights Organizations” is a collaborative project between Emory University's Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, and The Robert W. Woodruff Library of Atlanta University Center to uncover and make available previously hidden collections documenting the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta and New Orleans. The project is administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources with funds from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Each organization regularly contributes blog posts about their progress.

“Working for Freedom: Documenting Civil Rights Organizations” is a collaborative project between Emory University's Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, The Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, and The Robert W. Woodruff Library of Atlanta University Center to uncover and make available previously hidden collections documenting the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta and New Orleans. The project is administered by the Council on Library and Information Resources with funds from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Each organization regularly contributes blog posts about their progress.

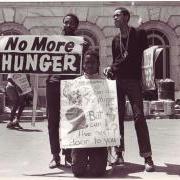

In the Spring of 1968, SCLC launched the Poor People’s Campaign. Though planning began prior to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the campaign itself did not officially begin until May. The first major action was the construction of Resurrection City on the Mall in Washington, D.C. Poor demonstrators traveled by mule train and bus from across the country to take up residence in the city and join SCLC in demanding food stamps, jobs and job training, and housing. Resurrection City was intended to be the embodiment of SCLC’s vision for the nation: a peaceful and loving community, fully integrated, free from greed, envy and want. It was also meant to be a stark example of the plight of the poor in America. As Ralph David Abernathy described it in his autobiography,

“All our citizens would start out equal because they would arrive at Resurrection City in equal need: No one would have a larger house or a fuller stomach merely because of what he or she had inherited. No one would have an advantage over another because everyone would have nothing. No one would need an extra push because no one would have a head start. No one would be greedy and no one would be envious. We would all be back on the frontier, where liberty and equality were not two mutually exclusive ideas, but achievable goals.” (And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, 503-504)

The first A-frame, plywood homes were constructed on May 13, 1968. During the days, officials met with staff at the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Labor, while residents demonstrated outside. However, Resurrection City was plagued with problems from the beginning. Though there were citizens from many ethnic backgrounds, city managers were never able to achieve integration. Ethnically based neighborhoods sprang up almost immediately. Additionally, many inner city youth recreated the gangs they had been used to at home, robbing other residents and contributing an atmosphere ripe for violence. Finally, heavy rains turned the grounds into a soggy, muddy mess and created miserable conditions for residents.

The demonstration culminated in a Solidarity Day rally on June 19, featuring a march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial and speeches from several notable civil rights leaders and politicians. Vowing to remain on the Mall until Congress met their demands, leaders applied for an extension on their lease on the grounds. It was denied at the end of the week, but conditions had already deteriorated to such a degree that Abernathy and others were unsurprised by the denial. Continued demonstrations at the Department of Agriculture on June 23 erupted in violence which spread to Resurrection City and ended with police throwing tear gas into the camp. By this time, many residents had returned to their homes and numbers had dwindled from several thousand to only a few hundred. On the morning of June 24, as police evicted the remaining citizens and began to dismantle the plywood town, Abernathy and many others were arrested during a sit-in in front of the Capitol. Abernathy spent 20 days in jail, fasting to call attention to the condition of poverty. During his incarceration, Abernathy received a great deal of mail in both support of and opposition to Resurrection City and the Poor People’s Campaign. Though Resurrection City had ended, the Poor People’s Campaign would itself be resurrected for several months in 1969.

|

| Above: Letter to Abernathy in opposition to the Poor People's Campaign, July 1968. Click images to enlarge. |

Note: Images may not be reproduced without the consent of Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. The names and addresses of private citizens have been redacted to protect their privacy. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference records are closed to researchers for processing. They are expected to open in 2012.