“Hair matters because it is a part of our being, of our very existence that has meaning on the level of ideas and materiality.”

–Ingrid Banks, 2000

Prior to my independent research for this article, I had encountered a variety of Black women photographed in the 1960s and 1970s with rounded afros and natural hairstyles. I thereby sought to uncover the underpinnings behind the transition from this apparent renaissance in Black women’s self-acceptance to the utter erasure of Black women’s natural hair from mainstream media. I found that this transition was enabled by numerous socio-political factors which illustrated the rise of the afro as an emblematic statement and the subsequent commodification and trivialization of the afro that followed.

The Impact of Judeo-Christian Indoctrination on Femininity Politics

The rigid, exclusionary expectations of a Eurocentric society are firmly entrenched in the subconscious of Western societies. These norms have inevitably been accompanied by standards of beauty, which disregard the context of non-European phenotypes, cultures, and geographies. Christian indoctrination since the era of the Transatlantic Slave Trade provides useful context for the analysis of the multifaceted complexity of Black Hair.

Throughout the duration of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the Church generally viewed slavery as a spiritually advantageous practice, portraying slavery as an act of religious subservience. The growing influence of Protestantism throughout the New World during the 16th and 17th century was accompanied by dynamic discourse regarding the feasibility of Christian education for enslaved people. Whilst many feared that Christianization would lead to eventual enfranchisement and empowerment of slaves, others deemed Christian education as a fundamental right and believed that it would encourage subservience. By the 19th century, a paternalistic perspective of Christian slavery at the intersection of evangelization and natural hierarchy had been widely accepted by white planters in the Americas and the Caribbean. Christianity therefore remained a point of aspiration for enslaved African peoples who aimed to assimilate to European culture, accompanied by its stipulations of marriage, customs, and respectability.

Eurocentric notions of femininity were heavily influenced by Judeo-Christian ideologies. Biblical excerpts such as 1 Corinthians 11, reference a woman’s long hair as being of glory to her. In this way long, flowing hair has become intrinsically linked to notions of femininity and subsequent respectability over the course of generations. The subvert war waged by a Eurocentric society on Black hair is one therefore of distinctive significance, as its immutable characteristics are portrayed as antithetical to femininity itself. These effects resonate throughout the personal, political, and socioeconomic spheres.

Black Women, Relaxers, and Femininity

Perhaps the most subvert, yet consequential facilitators of the multibillion-dollar hair relaxer industry, which is dominated by companies such as Soft-Sheen Carson, ORS and Avlon, is the orchestrated commodification of Black hair. In Susannah Walker’s article entitled “Black Is Profitable: The Commodification of the Afro, 1960—1975,” the nuanced reality of Black women’s natural hair is highlighted. Owing to the prevalence of the “Black is Beautiful” movement during this period, multiple Black Americans wore their hair in its natural state, largely as a stance of both economic autonomy from and political rejection of White American norms and notions of respectability. Unfortunately, Black women appeared to have received little respite from the onslaught of expectations of performative femininity.

“Gender performativity” is a term coined by Judith Butler, an American philosopher and gender theorist. It denotes the theory that a patriarchal societal structure has devised hegemonic delineations of what constitutes masculinity and femininity and opposes the concept that these expectations are intrinsic qualities of males and females respectively. Gender performativity is an area of complexity for Black women as it is entangled in the realities of both gender and race. In Bell Hooks’ Killing Rage: Ending Racism, she posits that dark skin and kinkier hair textures are associated with masculinity, whilst lighter skin and straighter hair textures are deemed more desirable, thereby creating inequality within Black communities based on color-caste. These preferred characteristics are not naturally possessed by most Black women, leading to the exhaustive expectation of overcompensation and assimilation.

Even within the Civil Rights Movement, women-identified activists were still expected to conform to preconceived beauty standards. Michelle Wallace, a Black feminist author and cultural critic in her essay entitled “Anger in Isolation: A Black Feminist’s Search for Sisterhood” expressed the frustration she endured after making the decision to sport natural hair during the Black Hair renaissance of the 1960s. Outlining the anxieties that accompanied her choice, she mentioned the limitations of occurrences such as rainy weather or time constraints for the maintenance of her hair. The state of her appearance still exerted dominance over her personal life in ways that did not impact her white counterparts. This exemplifies the perpetuation of ideas of Black hair as a site of arduous labor and inconvenience.

Not only were Black women subjected to scrutiny within their own communities in the 1960s and 1970s, but from society at large. In response to the revolution in hair practices, the mainstream beauty industry created new parameters of the “acceptable,” perpetuating the notion that Black women must still purchase products for the upkeep of their tresses. Through calculated shifts towards the optimization of the afro as a fashion statement, the aspirations of Black women wearing natural styles gradually shifted from an unbridled expression of self, to the pursuit of the most aesthetically pleasing “hairdo”. By reducing the afro to merely a hairstyle option for Black women, the initial subversive implications of the natural hair movement were diluted to enhance marketability whilst quelling concerns of White America. The demand for versatility between these options culminated in the popularization of relaxers towards the end of the 1970s, which was promoted as a method for Black women to achieve more stretched, beautiful “afros,” whilst receiving dexterity between straight and textured styles. The afro had successfully been commodified, and, like the trend into which it was disfigured, decreased significantly in popularity before relaxed or chemically treated hair was normalized by the mid 1970s.

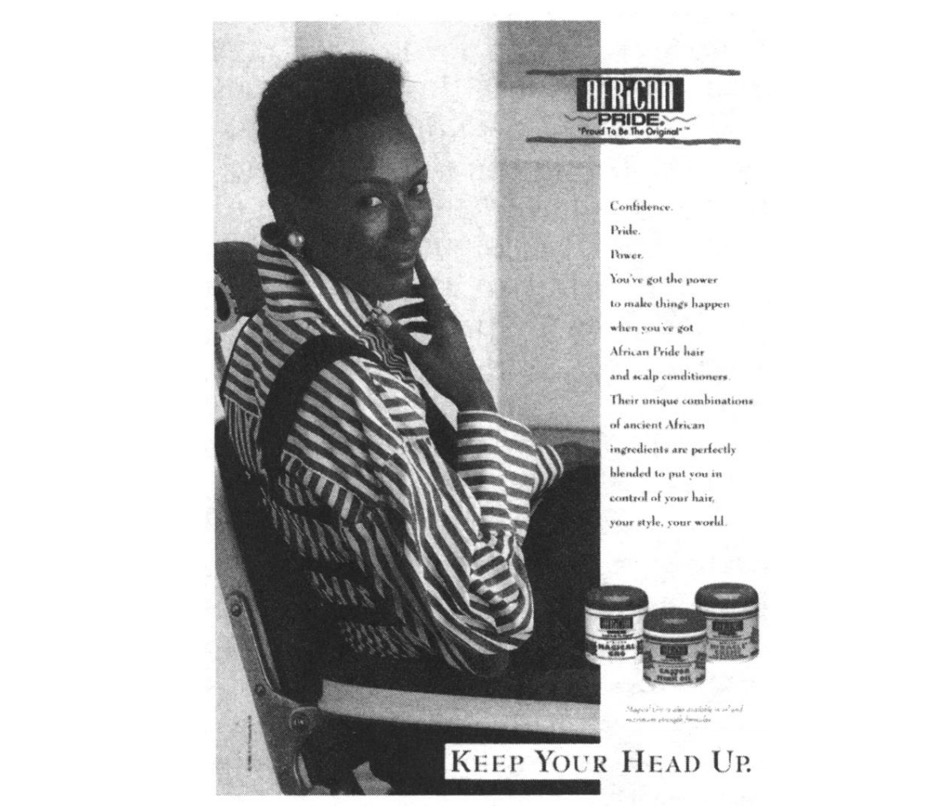

The era of relaxers in the Black community brought with it new lenses through which Black women viewed self-empowerment and social mobility. By the 1990s, the image of the progressive Black woman was one who had achieved manageable, “tamed” hair and successfully fulfilled standards of beauty and respectability, which were rooted in concepts of societal assimilation. A link between “conquering” one’s hair and, by extension, one’s femininity and “conquering” the professional sphere had been fueled by narratives within Black discourse communities. Essence Magazine, which was a pioneer for literature catering exclusively to Black women, frequently included advertisements for hair relaxers and other chemical modifiers in their issues throughout the early 1990s, whilst simultaneously endorsing themes of motivation and self-improvement. Words such as “control” designated Black hair care advertisements as a reserve of power, even when chemically processed.

How did these events affect the Black women as individuals?

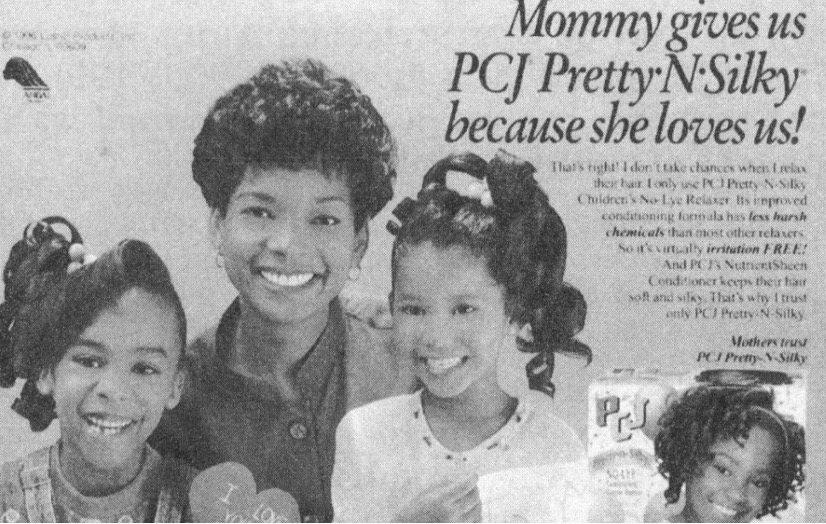

Since early childhood, Black hair often becomes a point of complexity for Black women. The hypersexualization of Black women from an early age serves as a pivotal point of analysis of hair politics in these communities. In Ingrid Bank’s Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women’s Consciousness, an anecdotal approach to perceptions of Black hair reveals these intersectional underpinnings. This is exemplified by an account of a Black woman’s experience at the age of four, where she recounts being berated for resembling a “boy” for wearing a short, cropped afro. This culminated in this woman receiving routine relaxers by the age of five. The link between the inferiority of naturally textured hair and femininity politics had already been solidified in this young woman prior to the onset of puberty. The industry of chemical relaxers had acquired a consistent patron.

The culture of Black women being met with admonishment when perceived deviation from rigid standards occurs is rooted in the desensitization to the personhood of young Black girls.

The evidence presented in a study published by the Georgetown University Law Center supported that the overwhelming majority of adults across demographics believed young Black girls to require less protection, nurturing, and possess greater exposure to adult topics than their white counterparts. This reflects a societal view of feminine traits such as innocence not only equating to respectability, but being antithetical to young Black women’s experiences. Therefore, hair being a point of non-conformity is synonymous with rejection and struggle, which historically designated the Black woman’s natural hair as inherently unfeminine.

The ungendering of Black adolescent bodies is also furthered by a society that perpetuates harmful prejudices on obesity and being overweight. In a study published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health a correlation was established between chemical-based hair maintenance and cardiometabolic health in Black women and girls. The intricacies of chemically treated Black hair maintenance limit the physical activity of young Black girls relative to their white counterparts. Swimming lessons after school may result in hours lost weekly to mitigate damage and degradation of hair quality. Not only does this lead to a perception of Black hair care a physical inconvenience that must be rectified, but these resultant disparities further the ideology of femininity as antithetical to the young Black woman’s experience.

Present Perspectives of Relaxers

Since the onset of the 21st century, empirical evidence supports that Black women have begun to deviate from the use of chemical relaxers. In accordance with data published by the Mintel Press team, hair relaxer sales declined by 26% between the years of 2008 and 2013. Despite these evidently promising strides, Black women of today are still subjected to discrimination based on adherence to Eurocentric notions of femininity. In a 2020 study published in the Journal of Economics, Race and Policy, it was found that whilst darker skinned Black individuals earned less than both men and women of lighter complexions, lighter skinned Black women still earned less, on average than lighter skinned Black men.

Black women have made collective progress towards healing from the wounds of systemic ostracization, trivialization and erasure of their hair textures, but the trail of destruction left in its wake cannot be ignored. Although empirical evidence capturing the scope of chemical relaxers is relatively sparse and inaccessible, links have been established between relaxer use and increased risk of alopecia, breast cancer and uterine fibroids. This, coupled with the deep-rooted implications of color caste-stratification therefore creates a rich intersectional platform for further research, discourse and reflection.

References

- Gaston, S. A., James-Todd, T., Riley, N. M., Gladney, M. N., Harmon, Q. E., Baird, D. D., & Jackson, C. L. (2020). Hair Maintenance and Chemical Hair Product Usage as Barriers to Physical Activity in Childhood and Adulthood among African American Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9254. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249254

- Banks, I. (2000). Hair matters: Beauty, power, and Black women’s consciousness. New York: New York University Press.

- Epstein, Rebecca and Blake, Jamilia and González, Thalia, Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood (June 27, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000695 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3000695

- WALKER, S. (2000). Black Is Profitable: The Commodification of the Afro, 1960—1975. Enterprise & Society, 1(3), 536-564. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23699596

- Mayes, E. (1997). Chapter 5: As Soft as Straight Gets: African American Women and Mainstream Beauty Standards in Haircare Advertising. Counterpoints, 54, 85-108. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42975205

- Wise, Lauren A et al. “Hair relaxer use and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women.” American journal of epidemiology vol. 175,5 (2012): 432-40. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr351

- Nash, Margaret. Hypatia, vol. 5, no. 3, 1990, pp. 171–175. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3809989. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- Hill, Mark E. “Skin Color and the Perception of Attractiveness among African Americans: Does Gender Make a Difference?” Social Psychology Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 1, 2002, pp. 77–91. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3090169. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- Reece, R.L. The Gender of Colorism: Understanding the Intersection of Skin Tone and Gender Inequality. J Econ Race Policy 4, 47–55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00054-1

- Akasha (Gloria T.) Hull, et al. But Some of Us Are Brave : Black Women’s Studies. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1982. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=1158354&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Brinton, Louise A et al. “Skin lighteners and hair relaxers as risk factors for breast cancer: results from the Ghana breast health study.” Carcinogenesis vol. 39,4 (2018): 571-579. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgy002

- “Hair Relaxer Sales Decline 26% over the Past Five Years.” Mintel, 5 Sept. 2013, www.mintel.com/press-centre/beauty-and-personal-care/hairstyle-trends-hair-relaxer-sales-decline.

- Nash, Margaret. Hypatia, vol. 5, no. 3, 1990, pp. 171–175. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3809989. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.

- “Christian Slaves in the Atlantic World.” Christian Slavery: Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World, by Katharine Gerbner, University of Pennsylvania Press, PHILADELPHIA, 2018, pp. 13–30. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv16t6j9v.5. Accessed 26 Apr. 2021.