[March 26, 2019]

I’ve often thought that people tend to represent their own culture in positive ways, both to outsiders and to themselves, while backgrounding or downplaying aspects that are less charitable. We proclaim marriage till death do us part while knowing that roughly half of marriages end in divorce. We extoll our core values of freedom and equality while knowing that racism, sexism, and ethnic and national and religious discrimination are rampant if not worsening. Gebusi of Papua New Guinea had an amazing – and real and deep – ethic of goodhearted friendship and camaraderie though their villages were wracked by suspicions and accusations of sorcery, traditionally including the execution and cannibalism of sorcerers within the community. In Atlanta, we have the uplifting values of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial – and a scant distance away, some of the most despondent, dangerous, and drug-infested African American communities. Around the world, people champion their culture and country, its positive values and past achievements, while avoiding the running sores and suffering that it tolerates if not inadvertently foments.

Over the years, I’ve seen this regularly in countries big and small – India, China, Mongolia, Liberia, Myanmar, Mali, Uganda, and so on. If not universal, it’s very common for people to emphasize their greatest values, highest ideals, and deepest benefits – especially to outsiders – while downplaying the dark side of their moon. In Mongolia, by the entrance to the national university entrance, there is a large statue of a Mongolian general who sent thousands of his countrymen to their death during the Stalinist purges. When I asked why in the post-Soviet era Mongolian graduates still pose for pictures under the statue, they said that the general was a patriot: his killings skillfully preempted what could have been a yet greater slaughter if the Russians had thought Mongolia was not taking steps to cleanse its own non-Communists.

Ideally of course, in our own ideology, being made aware of collective challenges and shortcomings problems redoubles our efforts to confront and solve these very problems – to make the values we seek more real in the lives we really live. But I don’t think there’s an easy way or litmus test to know or judge, especially for others, where the best balance lays between emphasizing the positive and exposing the negative of culture in society. Unbridled self-praise and unbridled self-criticism both carry excesses, carrot and stick – either emphasizing what is great and neglecting what is pernicious, or getting stuck in a negative cycle of endless critique and cynicism. While important and even crucial to investigate these dynamic, both among ourselves and among others, there’s no grand or independent position to from which to make Olympian assessments. Our view always has its own position, is typically fleeting, and is always partial.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

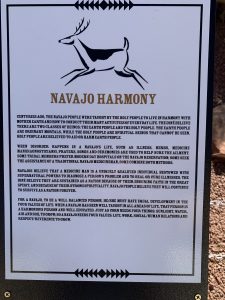

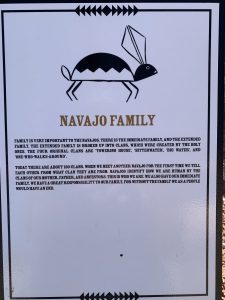

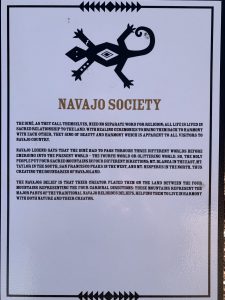

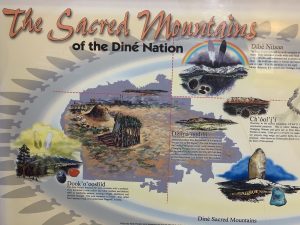

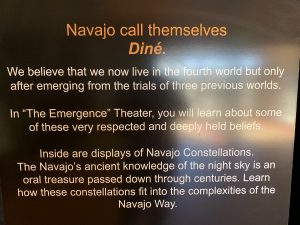

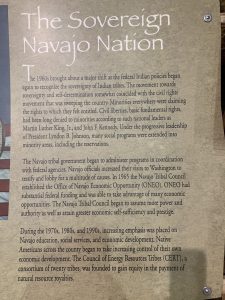

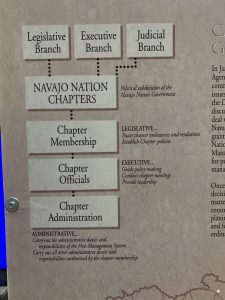

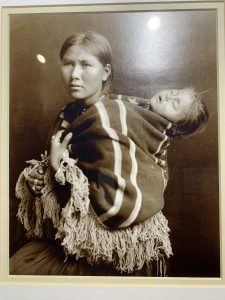

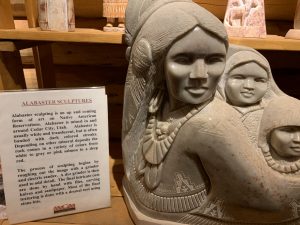

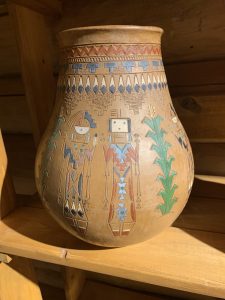

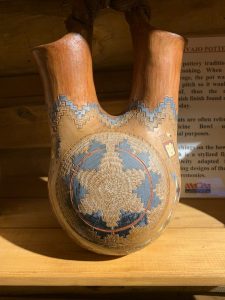

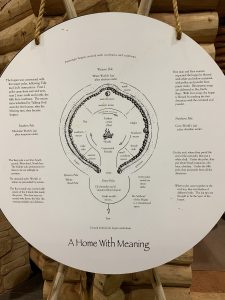

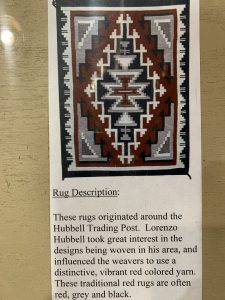

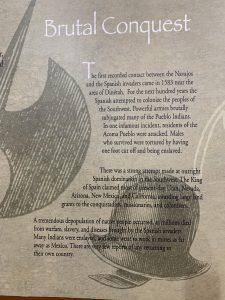

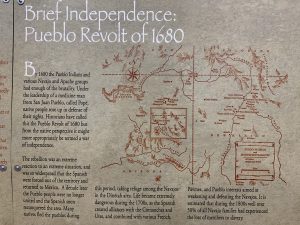

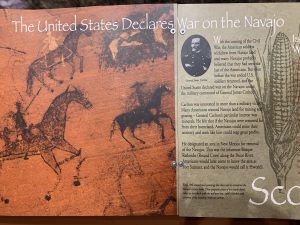

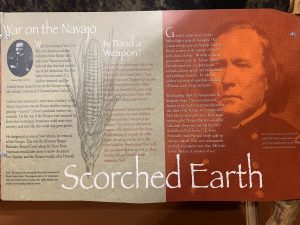

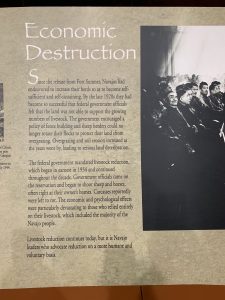

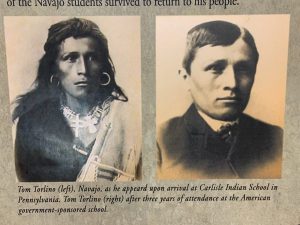

The Navajo museum in Tuba City, Arizona, is distinctive in being, and proclaiming itself, a representation of Navajo culture and history by Navajo themselves, not by outsiders. First presented on a national stage in Washington, D.C. a few years ago, the exhibition includes deep and wonderful depictions of Navajo culture, its values of balance and harmony, across people and environment, men and women, seasons and cardinal directions, domestic life, and even the structure of traditional hogan residence. Against this is cast, quite poignantly and factually, the horrific and debilitating intrusion of whites against Navaho, time and again, with scars that run very deep to and through the present. For me it was a very moving, powerful, and important presentation. Pictures tell part of the story.

= = = = = = = = = = =

Leaving the museum and driving from Tuba City to the National Monument of Canyon de Chelly – sometimes described as the longest continuously inhabited Native American site in north America, from BC to the present – one goes through Indian country, the officially designated nations of the Navajo and Hopi people, for one hundred and fifty miles. The landscape is as beautiful as it is barren, with breathtaking vistas and mesas and vast geographic austerity. And as poor and entrenched in apparent abject poverty as a human landscape as could almost possibly be imagined. We didn’t take pictures; it wasn’t appropriate to do so. This because poverty-porn tourism is our own Western affliction, and because it is not desired by Indians themselves; it seems disrespectful. Whites have been intruding on and hurting and objectifying and representing Native Americans for their own myopic and often calamitous purposes for so many decades and centuries. It is better to have sympathy for their desire for internal privacy than intrude, even if from a supposedly more progressive or enlightened perspective than was the case among Whites of yore.

To the eye, the human landscape seems stark. Shacks and hovels and tiny half-broken down houses dot the landscape at irregular intervals – with great stretches of nothing in between, a vast open vast country that is scorchingly hot in summer and brutally cold in winter. In the great majority of sites, there is no natural water and no water tanks; we are told later that water tanker trucks come to central staging areas for people to fill up and bring back what they can. Apart from the occasional run-down Indian craft and jewelry store and government service facilities many miles apart – a police station, a health care center, a school — there seems to be little visible commercial economy or specter of employment. We see no livestock or agriculture – no means of sustaining local subsistence. Self-contained in longstanding culture, bereft of material resources, and amid a larger world of unrelenting capitalism, what daily life is like, what it consists of in these harsh settlements, is hard for me to imagine. We know that rates of domestic abuse, violence, alcoholism, drug use, poor health, school drop-out, teen pregnancy, obesity, and overall morbidity and mortality are very high on many or most Native American reservations. We know as well that cultural values in these areas often remain very strong, including clan structure, tribal organization, respect for and authority of elders, and male predominance in extra-domestic politics and representation. We know as outsiders, especially as American white outsiders, that we have little right to intrude or pry or project or judge in ways that are not invited and not welcome. We continue on.

= = = = = =

At the National Monument of Canyon de Chelly, just outside Chinle, AZ, we meet Victoria (not her genuine name), our Native American guide. Her parents, both full blooded Navajo, were born nearby, and she went to school nearby in Chinle and then went on to college. She is fluent in English though says she feels much more at home in her native Navajo language. Interacting with her immediately feels like talking to someone from a very different culture. On prima facie grounds of self-presentation, interactional style, demeanor, and personal expression, she identifies and projects if not exudes that she is Navajo and not “Caucasian,” as she puts it. Victoria is nobody’s pawn and nobody’s fool. She says Navajo have always been rebellious and strong in character, and that Navajo women have been forcefully and forcibly carrying on their lives since the beginning. She contrasts this with the weak wilting feminine Whites that she says cower for protection and patronage from men; she curses disdainfully and says she has no use for them and for that. She herself seems nothing if not strong. We like her a lot.

Her jeep is tiny and dilapidated, with a ragged interior, but she takes us on board and drives it like the pro that she is deep into the canyon. She guns the engine right across the rushing river, the brown current splashing up all around us, swerving this way and that around rocks and holes she knows from experience. During the afternoon, Victoria repeats this heart-pounding exercise a score of times at various crossings, making 4-wheel tracks deeper and deeper into the canyon. She has never stalled out, she says. She seems to knows every bolt and bearing and tie-rod of her jeep and is keen to keep it running through good maintenance and service. Appearances can be deceiving. Still, for the passenger, the vehicle is tough. Twice I nearly wrench my knee trying to squeeze awkwardly from the back through the tiny space through the driver’s door down two feet to the ground below.

Victoria is now on spring break, visiting home and resuming the tour work that brings her income. Otherwise, she is finishing her Master’s degree in art therapy in Santa Fe, helping young people deal with trauma through art in an applied practica. There are very few Native Americans in the school she works at; she deals mainly with traumatized Hispanic children and immigrants, blacks, other persons of color, and a few whites.

The task at present hand, however, is for Kate and me to be native-guided to the ancient rock art in majestic surroundings at the bottom of the deepening canyon, framed by sky-scraping walls and deep azure blue above, the brown canyon river below. The place is incredible — and punctuated by vivid rock wall etchings and residential ruins high up on the canyon walls. It is hard if not impossible to convey in photos.

Victoria stops, draws a picture in the ground with a stick, and tells us a telescoped history: how the ancient Anasazi were confronted and eventually displaced from this canyon by the Athabascan-descended Navajo; how they and the Anasazi-descended Hopi have always been tribal enemies and rivals. She tells how the Hopi have always lived in pueblos, more sedentary, while the Navajo ranged widely as pastoralists with sheep and goats, attacking and supplanting the Hopi when they could. The current Navajo possession of the place seems to bring this history to the present, including Victoria’s authoritative role as a Navajo presenting to outsiders the ancient art and habitation of her tribal enemies. On the other hand, she says, when the coal seam mining that would further devastate their landscape was refused by the Navajo, the land was reassigned to the Hopi by the U.S. in the 1980s during the Reagan years. Hopi, she says, were happy to approve the intrusion of mining, and its potential royalties. The mine was later shut but might now be re-opened; the issue is still hotly contested, both within and across tribal lines.

As we continue deeper, we find more stunning sites and stunning relics. But the most intriguing is Victoria herself. She describes the rock walls and how she has clamored up among them. She knows the area well and used to tend flocks of sheep – a skill her grandparents required but which is now practically lost on a younger generation. She remembers being so tired from herding that she would sometimes fall asleep during supper. But unlike many other children, especially now, she enjoyed the freedom to be outside and roam with the animals.

Not long ago, she and one of her brothers took an extended canyon hike along steep sections of the canyon, she says. He brought along a tough tattooed friend who joked boldly how he would leave Victoria in the dust. As the day wore on, the guy could barely continue. At the end, as it was getting dark, there was yet more rock to climb out of. The young man lost it and started to cry. She mimics with a smirk how he literally cried that he wanted his mommy. Victoria said she was not impressed but disgusted; she left her brother behind to pamper the guy while going on alone to get out of the canyon and go home.

Shortly later, we get to a Navajo homestead in the remote recesses of the canyon. It belongs to an old woman who is presently away; Victoria volunteered to feed her sheep while she was gone. The week before, several of the sheep were killed and eaten by mountain lions; the woman’s son, who was there at the time, shot them with his rifle. The old woman is a good shot, too, she says. The compound is strewn with equipment; it was bought by the son, who is in the military and supports her mother. But even without him she’d be OK, Victoria says; Navajo women are survivors.

We ask why there aren’t more homesteads in the canyon. Victoria scoffs that people don’t keep up their vehicles and so can’t live there; most Navajo don’t have cars or trucks that are used and maintained withstand all the sand and the high water-crossings.

We talk about politics, and men. Victoria says Navajo men look down on women in politics. In fact, she says, Navajo men are so committed to the idea that women should just do domestic work that they think the land itself will cosmically end if women have official control. Most Navajo men would never vote for Hillary Clinton. She says with disgust and a vivid curse that almost all of them voted for Trump. Despite decrying politics, they still take it up themselves, she says. She points up the hypocrisy of those men who know little tribal knowledge or legacy while presenting themselves political paragons of the tribe.

Of children and family Victoria will say nothing. And vigilantly so. When I say I have a son and ask is she had any kids, she curses me and says its none of my business, that whatever fantasies I may have about her will never be responded to. I look over to Kate a bit bewildered. I say that most cultures have some customs surrounding families and kids and gender. She’s not interested and not impressed.

Victoria is more interested to know about witchcraft, especially New Age wiccan beliefs in the West. I tell her about Lurhmann’s Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft, about wiccan practices and magic ritual in contemporary England. She says Navajo continue to have active traditions of traditional curing and shamanism. She is intrigued to know more about how Western women were killed as witches through the 1600s and talks about the hypocrisy of Caucasians.

We talk about young people and schooling and teenage. Victoria says it’s not hard for a qualified Navajo to get a scholarship or fellowship for higher education or credentialed training. But this is such a leap of language and culture that it is very hard — and was very very hard for her. Her sister is now studying to become an anthropologist at a college in Durango; she received a scholarship from a philanthropist’s program that pays tuition for any qualified Native American. But Victoria scoffs at the rich white do-gooder who set up the scheme. She says it is hard for her sister, who is resented by non-Indians for getting support. I ask what the Navajo guys do who don’t go on in school, and if there are any gangs within or between the tribe’s major clans. She says no, but that some of the guys pick up rap music and identity with Red and Blue gangs from the outside. The gangs are brutal and violent; people get killed. And its hard to escape them. She says one Hispanic guy trying to escape his gangs, in Santa Fe where she works, was captured and brought all the way back to Honduras. She says she tells young Navajo guys that they are already strong warriors and don’t need to mess with such stuff from the outside. But it’s hard for them to listen, and they mostly ignore her.

Victoria herself comes from a prominent and far-flung Navajo family. Her own brothers include some successful professionals, but none in areas that jibe with her own interests. Except for her father, whose interests include a horse-riding outfit in the canyon. But she says she hasn’t spoken to her father in eight years. We don’t ask why.

Victoria says that she “doesn’t do groups.” By example, she mentions with smirking hilarity an African American woman who wanted to set up a persons-of-color meeting group in relation to the counseling program she is in. When the woman kept inveigling her to join, Victoria said she had a caustic open argument with her. The last straw was the woman wanted to arrange a meeting – during their week of spring break, no less — to “reach closure” on the issue. “Why the fuck do we need a damn meeting to reach closure what is what is already done, finished!”

Even with her natal family and her tribe, Victoria seems wary of deeper group entanglement. I ask if Navajo who get more educated tend to go back to the tribe or tend to move away and not come back much. She says mostly the latter. Despite her own deep Navajo-ness, this will also apparently include Victoria herself. She wants to live in Santa Fe and then probably in Albuquerque – and not in close relation to a Navajo community or extended family in either place. She all but says that her Navajo-ness is to fully self-sufficient. She talks about the need and necessity and yet the difficulty of living in a Western world for career and money and life while being so alien and apart from it by cultural background and depth of feeling. As if being tough and surviving across two completely different worlds is not ultimately unfair, but simply life.

For the moment, Victoria is finishing her art therapy counseling program. Her having become aware of and enticed to enter the program she ascribes to chance, to idiosyncrasy, and to the actions of others — rather than to her own acumen and interests and intelligence and energy. We encourage her and say she is obviously smart and dedicated and incredibly energetic and has so much to give others. She doesn’t get cross with us but lets the conversation trail off as we start driving out of the canyon.

Bringing us back to her office, Victoria is back in business. It is a one-room affair with a sign out front – the only one in the Canyon that lights up, she says — and what appears to be an alcove to sleep in. Out the window of the jeep as we pull up, she yells some directives to the young guy who seems to be minding her fort aimlessly in her absence. Impressively, we are back as planned on the dot of 4:30pm – so Victoria can pick up her next clients, another couple who will also get the tour to the canyon’s depth and be back before the end of dusk. No one but Victoria seems materially involved in her operation; she appears to be a one-woman band.

The trip costs $200. I add on a $50 tip and she thanks me. In immaculate script, she writes me a receipt from her well-kept book.

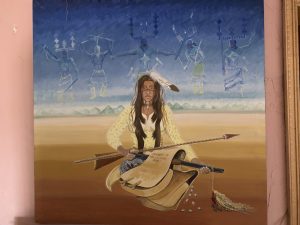

I ask about the intriguing paintings and artifacts on the walls, and she says she herself made them.

The one on the opposite wall that she painted is of a seated woman holding an arrow, with Navajo spirit guide symbols overhead. Victoria says the mythic woman is her own spirit guide, a link through her great-grandmother to ancestral land that her family still sometimes visits. She says the woman was an Apache from long ago who came here. The men tried to kick her out, worried that she would take root and claim land. They tried to capture her and take her away – but she hid cleverly and hung on, surviving till they gave up and left, and flourishing on her own thereafter. Later she confronted the U.S. Army; the painting depicts a rifle and the saddle bag she captured from union soldiers in 1880, plus the scalp trophy she took from one of her victims. I ask if I can take a photos of it, and of her in front of it. She agrees. I snap my pics.

Then her attention turns to her next waiting clients.

= = = = =

In my freshman seminar, we talk about what it is like for people of mixed race and mixed culture to live between alternative worlds. Of how people suffer across such junctures, what they lose, and what they also gain and may even grow stronger from in the process. Would that that trails of tears lead to greater victory. Including here.