After Arkansas, Oklahoma, northern Texas, and New Mexico, Sedona Arizona seems so Blue and so White. And to one who is so Blue by choice and so White even if by not so, it can’t help feeling good and fun and comfortable – the happy people, the stunning scenery, the amazing sunsets, the trendy shops, the biggest Whole Foods imaginable, the so-casual so-pretty and so-chic, picture postcard become seemingly real. Just look at the photos!

As for people, everyone – it seems – is liberal and accommodating if not downright progressive. Not that this shouldn’t be enjoyed. But rather that this enjoyment, even in sublime depth, has its own context.

Like when I go on an exhilarating 8-mile solo hike through awesome canyon country. To begin with, there are hundreds of trails to be walked in the region; which is best for a one-day one-person excursion? Along with suggestions from family and friends back home, Kate has presciently packed the third edition of Hiking the Southwest’s Canyon Country. So I find – barely a mile from our cut-rate but still “Diamond Resort” off of Bristlecone Drive, just far enough outside town to be beautiful – the highly rated “Soldier’s Pass Trail.” This is described as “arguably the finest walk in the Sedona region.” But among all those visiting from other places and races and traces, who would know about it, be close enough to realistically access it, and be able to enjoy it?!

Getting there is both easy and not — unless you have inside information. Take a left on a busy street in town, go 2 miles into seeming unmarked nothingness, then turn right on a subdivision street called Rim Shadow Road, then see gobs of “do not park here” warnings and signs. So I park a mile down the main road, lined with other cars tilted one side down the gullied shoulder, and walk back up. Then there is the trailhead, sandwiched between two sublime MacMansions, with the huge red and white rockface of the canyon on either side beyond.

The trail, the views, the hike are all amazing. Who would have guessed it? Answer: the others who are also enjoying it.

Socially, walking the trail is like re-living an episode from Leave it to Beaver or Andy Griffith in Mayberry R.F.D. At least on the outbound portion, it is well-traveled; I passed or otherwise encounter perhaps a hundred and fifty people, mostly in 2s and 3s and 4s. Everyone seems to be smiling and exchanging pleasantries: “Beautiful day!” ‘Awesome view!” “So much fun!” “Couldn’t be better!” and so on and on. I volunteer to take a pic of a pair of couples who are otherwise posing for each other in front of a scenic backdrop. They heartily agree and then reverse the favor. One of the couples is from San Francisco, the other from Kansas City; they have known each other for ages.

I am reminded of the photo in Jim Ferguson’s Expectations of Modernity, in Zambia, where he documents the passing and in-the-moment sincere but superficial connection of the cosmopolitan. That encoded selfie with strangers who appear in representation as close friends. What is shared and visually encoded is nothing but an empty icon of presumptive connection. An icon based on what?? The presumptive affinity of shared life-style and class and in this case racial identification. Not that this is bad or not fun. But rather that what this is and what it marks, is, in retrospect, marked by implicit exclusion as well as explicit inclusion. I remember only that one of the men was friendly to the point of being almost petulantly jokey, and that the friendlier of the two women was “Stacy,” from San Francisco. I remember almost nothing else except, as mentioned, the other couple was from Kansas City, and that he worked in management for the Royals. The four of them seemed upscale, fit, intelligent, knowledgeable, upper middle-class, happy, middle-aged, presently unencumbered by kids – and White.

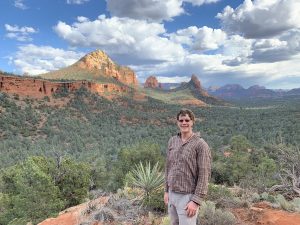

After encountering Stacy and the other three, I realized that almost all of the others I was encountering on the trail were also White. This continued throughout the day – including the guy with the big University of Michigan T-shirt and cap, with whom I stopped to share an alma mater connection. And another couple, who took the breathtaking shot of me below:

Very very few of the hikers seemed to be Hispanic (though admittedly, appearances can be deceiving amid hyphenated backgrounds and mixed-race couples). I didn’t see a single African American – or perhaps just one who was very light skinned. I didn’t see a single person, at least visually, who I thought could be Native American – or even Asian, for that matter. This in a state that is 27% Hispanic, 4% Black, 6% Native American, and which attracts international visitors from around the globe.

I thought of the environment, of how much of our fact-finding and pursuit and experience of natural beauty, how much of our physical energy and money in the quest, and how much our worry about the fate of our planet, is inflected by class and race and nationality. I thought of who was most able, and not, to enjoy the sublime nature that I had the special privilege to experience. It was not unspecial as a result. But it was missing Others.

= = = = =

It turns out that Soldiers Pass was a key U.S. conduit for supplies and men in American wars against Native Americans.

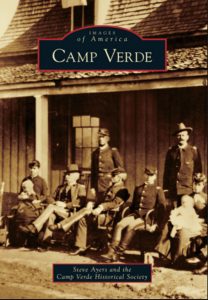

The trail is, “aptly named after the soldiers in the mid-1800’s who used this trail to camp along on their way to and from Fort Verde, now Camp Verde.” <https://www.elportalsedona.com/2016/02/11/sedona-hiking-trails-soldiers-pass/>.

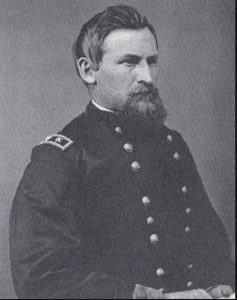

In 1871, Lt. Col. George Crook was named commander of the Military Department of Arizona. He established himself at Fort Verde in 1872 after having waged successful wars against Indian campaigns against the Shoshone, Nez Perce and others in Oregon and California.

See < https://www.azcentral.com/story/travel/local/history/2015/06/11/arizona-military-history-fort-verde/28713615/>. The account continues:

“Camp Verde served as a staging base for military operations in the surrounding countryside. Crook launched his campaign in November 1872, saturating the Tonto Basin with columns of troops and pursuing Indians relentlessly during the winter months. As each band surrendered, they were relocated to a reservation. In 1873, the Tonto Apache leader Chalipun and 300 followers traveled to Camp Verde to surrender to Crook on the porch of the commanding officer’s quarters.

From 1873 to 1875, nearly 1,500 Indians from various tribes were placed on the Rio Verde Reservation near present-day Cottonwood. The Indians were assured that this would be their home as long as “the rivers run, the grass grows and hills endure.” With the Army’s help, irrigation ditches were dug and crops were planted in the fertile valley.

But in February 1877, the Indians were moved to the San Carlos Reservation near Globe. Nearly 100 of them died during the brutal 180-mile march.

When the hostilities ended, President Ulysses Grant promoted Crook to brigadier general. He remained in the Arizona Territory until 1874.”

It should perhaps also be noted that Crook was considered, by standards of the time, to be one of the most humane and ‘enlightened’ of the Indian outpost commanders. He “respected his adversaries and was always willing to negotiate.” Crook himself wrote, “When they were pushed beyond endurance and would go on the warpath, we had to fight when our sympathies were with the Indians” (ibid.). “Crook … hired Indian scouts … [and he] paid his Apache scouts the same as the White scouts. Many of his superiors were skeptical, but Crook’s instincts were correct. Indian scouts from Fort Verde were awarded 11 Medals of Honor.” One senses here the beginnings of the intense and complex historical engagement of Native American men with U.S. military service. During his years in Arizona, through 1874, Crook, it is said, “continued to build roads, repair forts and became an outspoken advocate for the humane treatment of Indians” (ibid.).

= = = =

Oh, the complexities of race and war and struggle and beauty and environment, and that of it which is left and vouchsafed for some of us at least to deeply enjoy. Both this and its larger and deeper context seem important not just to recall but to instill and encode.

This on the weekend when the world reels from the New Zealand massacre of Muslims. And, simultaneously, while Trump tweets for reinstating “Judge Jeanine” — Fox News host and former prosecutor Jeanine Pirro, whose show was pulled after her on-air suggestion that Congresswoman Ilhan Omar of Minnesota did not support the Constitution because she is Muslim and wears a hijab. Against this, Trump tweeted, “Bring back @JudgeJeanine Pirro. The Radical Left Democrats, working closely with their beloved partner, the Fake News Media, is using every trick in the book to SILENCE a majority of our Country. They have all out campaigns against @FoxNews hosts who are doing too well.”

I can only hope that the progressivist spirit of Sedona, amid and despite its own contradictions, is somehow doing yet more honestly and deeply well.