the Rev’d Jay Weldon, Parish of the Good Shepherd, Waban, Massachusetts

Introduction

I am an Episcopal priest and I preach almost every Sunday. I receive all of the comments that most preachers do, as well as occasionally words of misunderstanding or simply not understanding. Sometimes they are substantive, but usually we barely scratch the surface. I once even had an older woman thank me for my lovely sermon on a day I hadn’t preached. Like other preachers, people like to compare me with others who have preceeded me in a particular place. I have heard this go both ways, that I am a better preacher or that there will never be another great preacher like she was. And now that I have completed my first major transition, I know that a poor young priest is having his sermons compared to mine by people who may or may not have been substantively challenged when I was their priest. All of this leads me to believe that it is very difficult for preachers to know whether or not we are missing the mark. Most of us are busy enough dealing with daily expectations that we hardly get the chance to answer this question, but that was the place where I found myself at the beginning of this project, wondering if there is a path toward excellent preaching in a particular tradition (in my case, the Episcopal Church) that is more identifiable and concrete than being compared to the previous rector.

Beyond this, churches are all going through massive changes. Overall the statistics are not good, but there are parishes that continue to defy trends—whether by growing, avoiding decline, or by developing more robust and authentic ways of being a church. I have attended seminars and classes on church growth. I have become convinced of a society that is less Christian, of people who no longer show denominational loyalty, and of millenials who have no religious formation. I bought books on how various efforts—social justice, community involvement, guest cards, praise and worship music, traditional music, coffee hour—might solve these problems. Some of them were quite good and I learned a lot from them, but somewhere along the way I came to believe that there wasn’t just one thing that would solve our problems. We had to face all of these. Maybe the answer was social justice and guest cards and community involvement and worship.

Finally, I discovered something that helped me synthesize both of these strains of thought—both the question of preaching and of leading a church into the future in a meaningful way. In a 2014 sermon, Bishop Eugene Sutton (Episcopal Diocese of Maryland) reflected on issues of declining membership, spiritual malaise, and a lack of vision that has plagued Mainline Protestant denominations. His description of the decline was predictable, though his vision for the Episcopal Church (and traditions like it) was unique. Our first call is to worship well. He cites Matthew’s narrative of the resurrection, of Jesus’ instructions to go to the mountain in Galilee, where his disciples worshipped him before he sent them into all the world.[1] This, Bishop Sutton claims, is a foundational image that teaches us the importance of worship in times of uncertainty and doubt. [2] The bishop’s sermon ends with both challenge and proposal:

The problem for [liturgical churches] is not that we are neurotically and unhelpfully fixated on music and liturgy. Rather, the problem from an evangelical and church growth stance is that we are not focused enough on worship. Good worship consists of its own “three legged stool”: music, liturgy and preaching. Each leg of that stool is important, and if one of them is weak, the others will not be able to stand for long. The truth is no matter how earnestly a church may pour itself into serving its community … if the preaching is uninspiring, the liturgy sloppy, or the music barely listenable, then that church will shrink and may have to close its doors as a worshiping community. This means that growing churches … are going to have to insist that their clergy spend more time, effort, and training on becoming good preachers, not settling for mediocre preaching. Ultimately, the reason for this turn, or “return,” to worship isn’t … to make us “feel” good, or to achieve some vague spiritual high. The reason [we] must focus on worship is to prepare to make disciples of all nations. It is to take seriously the first call of Jesus before the great commission to “go to the mountain, see Jesus there, and worship him.”[3]

Sutton offers a provocative and generative image of the elements of worship working in tandem, with a “practical three-legged stool” that envokes both priorities and intention. Those of us who stand in the pulpits of churches like his know how challenging it is for such synthesis to occur weekly. For preachers, there is the task of crafting and meaningful sermons Sunday after Sunday, striving for consequential preaching in a particular place and time. Preachers in every generation look for compelling ways of doing this, of attaining to a goal of excellent preaching. I suspect I join others in asking how best to attain to excellent preachning, particularly in a tradition relying heavily on scripture, liturgy, and sacrament.

The second challenge exists outside the pulpit. It is there that people engage sermons by listening and discerning meaning, and it is there that the task has grown increasingly complex. The year that I was born, Fred Craddock was encouraging preachers to understand how their listeners filled the pews each week with the Christian story safely in hand. Preaching needed to forego the temptation of simply telling the story to people who already knew it, he said, and instead it needed to engage the gospel more existentially. He harkened back to Kierkegaard and his observation that there was “no lack of information in a Christian land.”[4] Now, years later, the state of affairs in the pews is variegated if not altogether different. Some know the stories of the gospel and understand the patterns of worship. Others have been raised in the church and speak Christian well enough to get by, but poor catechesis and irregular patterns of engagement mean that they lack the kind of fluency in Christianity that Craddock assumed forty years ago. To this we add those who know so little about Christian stories and practices that almost everything could well be explained anew. Tom Long looks back on the sea change that has occurred in the last forty years and observes how different the world is now than it was for the likes of Craddock and Kierkegaard, writing, “now there is a lack of information and it isn’t a Christian land.”[5]

Soren Kierkegaard

Paul Scott Wilson also speaks of the changing needs of preaching derived from sweeping changes in culture: “Homiletics cannot avoid addressing facts like the decline in mainline church membership, newcomers with little or no church background; many philosophies, religions, and groups competing for an individual’s interest, loyalty, and time; mass media altering how people think and the rules for good communication; and erosion of the authority of institutions and their representatives, including preachers.”[6] There are not many givens in the pews today, and the preacher has to attend to various levels of fluency and familiarity with the Christian story.

In the liturgical tradition Bishop Sutton describes, preaching almost always occurs in the structure of a prescribed liturgy. This means the rhythm of the liturgy and of common prayer assumes predictable liturgical components that precede and follow preaching. Scripture, liturgy, homilies, prayers, and sacraments live together in each act of worship. Each worshipper has the opportunity to connect to the divine through various means, but it also means that much more is offered to each person than just what is proclaimed from the pulpit. Cultural shifts have not only affected how people are prepared to hear a sermon, but also how they might experience and understand the various claims made throughout the liturgy, or how they might fail to experience and understand such claims. Common prayer no longer means similar assumptions.

At its best, preaching in liturgical contexts helps to connect all of these elements so that everyone engaged in the act of common worship can worship fully. At its worst, it can come off like a clumsy interruption amidst liturgical formulations, scriptures, and prayers. With Bishop Sutton’s proposal in mind, we might agree that preaching is a matter of life and death for the future of the church, though we must also describe and articulate what we mean by excellent preaching, especially in the face of the present challenges that face the church. Preachers must consider the seachange from Craddock to Long and proclaim the gospel in a world that is no longer so easily described as Christian, and in churches where catechism cannot be assumed.

This paper explores excellence in preaching in order to respond to the new realities that face the church. Particular attention is given to the task in terms of Tom Long’s claim, that we are in a world where little can be assumed in terms of faith formation and catechesis. This work explores the particular hallmarks of liturgical preaching in order to identify how a sermon— situated alsongside scripture, common prayer, and sacrament—can engage people in a way that helps them to worship more fully.

To anticipate the argument, I will first suggest we think of sermons as an essential part of sacramental action. Second, I will explore how liturgical preaching functions with its own unique assumptions and resources. Third, I will suggest a three-legged stool of liturgical preaching that consists of scripture, narrative, and liturgical reflection, exploring how these elements coexist in the sermons of two exceptional preachers. Finally, I create and evaluate seven sermons with this three-legged stool in mind. The approach identified here will not solve all the challenges facing homiletics in the contemporary world. It should, however, prove useful to preachers who seek to engage changing realities, chiefly (but not limited to) those who preach in a liturgical tradition. That liturgical tradition, in turn, reminds us that preaching is about more than knowledge; it is an essential part of the church’s sacramental celebration and the unseen grace that they offer. In this era of dramatic change, Bishop Sutton suggests a vision of liturgy, music, and preaching that are excellent. This project attempts to attain to such a vision of preaching in a real, concrete way.

Uninterrupted Liturgy: Against Dualism in Word and Sacrament

History and tradition suggest that preaching is fundamental to the function of worship. Justin Martyr thought of preaching as the imitation of noble things that leads to Eucharist.[1] Augustine thought preaching should inform, delight, and persuade.[2] Cranmer wanted people to understand sermons as they understood worship, and the Oxford Movement viewed homiletics as a means to recover devotion. Each of these reminds us how preaching is essential in liturgical worship. Sometimes, however, despite the best of liturgy and music, the sermon comes and we press pause on worship. The preacher comments on how difficult the scriptures are. He talks about what his family did during the week, trying to relate to the scriptures. The homilist extoles a new windmill farm in Scotland,[3] making mention of a discussion on NPR. These scenarios are not just imaginable but they happen, and sometimes the sermon can disrupt the flow of worship.

Robert Waznak, writing from a Roman Catholic perspective, calls this a liturgical interruption. “In the early 1960s some liturgists were referring to the homily as an ‘interruption’ in the liturgy rather than an integral part of it.”[10] Worrying about people’s ignorance, some saw the liturgy as a platform for doctrinal instruction. Others saw it as unnecessary when the Zeitgeist focused on the renewal of liturgy. Under these circumstances, he suggests, the sermon became “an ‘interruption’ in the liturgy.”[11] Protestants, too, have struggled to imagine how sermons live alongside sacraments after centuries of worship centered on preaching. Sermon and sacrament have different identities, and we often juxtapose them into a dualistic encounter.[12]

The opposite of this dichotomy is to say that sermon and liturgy are of the same essence. R. H. Fuller writes, “the liturgical sermon announces the action of God which is to occur in and through the whole Eucharistic action, including and culminating in the communion of the people… to renew in the individual members the sense that they are members of the ecclesia, constituted as such by the redemptive act of God in Christ.”[13] Fuller also calls this unity necessary because, “divorced from its proper context in liturgical action, preaching… becomes intellectualism, moralism, or emotionalism.”[14] Todd Townsend says preaching and sacrament “share a ‘deep’ theological structure… and the deep theological dynamic structure of preaching not only coheres with the deep structure of sacrament, it is identical.”[15] He suggests that the sermon exists somewhere “between the font and altar,”[16] and it is preaching that makes sense of the journey from baptism to Eucharist. Each of these help both preacher and worshiper to envision the sermon as deeply important to the liturgical action.

A nuanced perspective comes from Wilfired Engemann, who offers an image of the “singleness of Word and sacrament,”[17] that extends a Table image to the sermon. He suggests that a Eucharistic context reminds us that we speak not only of God, but that we are speaking to God, because Christ sits at Table with us. The early church knew nothing of the division of Word and Sacrament, he says. Eucharistie und Verkuendigung were an inseparable union of Agape.[18]

A nuanced perspective comes from Wilfired Engemann, who offers an image of the “singleness of Word and sacrament,”[17] that extends a Table image to the sermon. He suggests that a Eucharistic context reminds us that we speak not only of God, but that we are speaking to God, because Christ sits at Table with us. The early church knew nothing of the division of Word and Sacrament, he says. Eucharistie und Verkuendigung were an inseparable union of Agape.[18]

Beyond a theological marriage of sermon and sacrament, homiletics can help make sense of liturgical action. John Baldovin offers a helpful definition, that liturgical preaching “is not about preaching in general but rather about the homily in the context of liturgical celebration.”[19] He claims a sermon is part of the broader sacramental action. “When one preaches liturgically,” he writes, “people should have some sense of why we proceed to make Eucharist, to witness marriage vows, to baptize, etc.”[20] To him, moving beyond dualism of sermon and sacrament is essential on both sides. Not only does the sermon rely on the sacrament, but the sacrament also relies on proclamation in order to make sense of it, for those in the pulpit as well as in the pew.

From Philosophy to Practice: Imagining a Liturgical Sermon

I begin here with a sentiment that is echoed wherever preaching is discussed: “Those of us still living in the shadow of Karl Barth whisper the subject, anxious that his ghost may rise to threaten us.”[21] No discussion of modern homiletics can proceed without referencing images shaped by Barth. Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, at the time of his retirement, offered a word of advice for his successor. Calling Barth “the greatest theologian of the twentieth century,” he reminded Justin Welby, “you have to preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other.”[22] This advice permeates homiletics, from professors to archbishops to pastors; few practitioners of homiletics ignore this as foundational in approaching preaching.

I begin here with a sentiment that is echoed wherever preaching is discussed: “Those of us still living in the shadow of Karl Barth whisper the subject, anxious that his ghost may rise to threaten us.”[21] No discussion of modern homiletics can proceed without referencing images shaped by Barth. Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, at the time of his retirement, offered a word of advice for his successor. Calling Barth “the greatest theologian of the twentieth century,” he reminded Justin Welby, “you have to preach with the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other.”[22] This advice permeates homiletics, from professors to archbishops to pastors; few practitioners of homiletics ignore this as foundational in approaching preaching.

For an investigation of liturgical preaching, it is worth exploring how Barth concieved this unity of proclamation and sacrament. “By reference to baptism and Communion,” he wrote, “the origin and aim of preaching [and] the course it pursues, are more clearly defined; the place of the messenger of the word is more plainly seen.”[23] “The preacher may point to the sacrament on the one hand and holy Scripture on the other.”[24] With this also considered alongside Barth’s image of Bible and newspaper, we may envision a new image of the preacher’s task. Liturgical preachers go into the pulpit with a Bible in one hand, and with the newspaper and a prayer book in the other. The preacher is tasked with making sense of the scriptures, the stories of life, and also of making sense of liturgical action. The rhythm of the church year, movements of the lectionary, and making sense of the actual words of the liturgy itself on a particular day (moving to font, altar, or some other sacramental rite), fall to the preacher in helping worshipers to make sense of liturgical action. As mentioned previously, this is no small task when parishioners bring with them such a varied corpus of religious understanding. Paul Scott Wilson describes this challenge regarding biblical literacy, though I would extend it also to the fullness of the liturgy: “Scholars in homiletics are in general agreement concerning Barth’s error. The preacher cannot assume to have a biblically literate or even interested congregation.”[25]

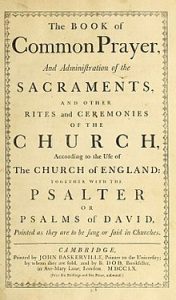

In the pulpit each Sunday, homiletics is not a philosophy but a practice. Making sense of liturgical action  alongside scripture and story might begin as a theoretical proposal, but it also moves us, “from a philosophy of preaching to a practice of preaching,”[26] in order to explore how we engage observations about preaching in a liturgical context practically. In the Anglican tradition, Richard Hooker’s image of the three-legged stool of scripture, tradition, and reason, has shaped theology as well as thought and action. It suggests a complexity and interdependence of religious aspects, which extends to preaching. Conceived as such, his image offers us a way of “practicing” liturgical preaching in a practical way. This allows the preacher to go into the pulpit and attempt to make sense of scripture, newspaper, and prayer book, all in a cohesive way.

alongside scripture and story might begin as a theoretical proposal, but it also moves us, “from a philosophy of preaching to a practice of preaching,”[26] in order to explore how we engage observations about preaching in a liturgical context practically. In the Anglican tradition, Richard Hooker’s image of the three-legged stool of scripture, tradition, and reason, has shaped theology as well as thought and action. It suggests a complexity and interdependence of religious aspects, which extends to preaching. Conceived as such, his image offers us a way of “practicing” liturgical preaching in a practical way. This allows the preacher to go into the pulpit and attempt to make sense of scripture, newspaper, and prayer book, all in a cohesive way.

Building on the three-legged stool images of both Hooker and Sutton, I suggest that there is a practical stool of liturgical preaching that consists of scripture, narrative, and liturgical reflection. The combination of these three components offers cohesion that is important in liturgical preaching, and it also engages that which is already present in worship. Evidence of this particular combination exists in the sermons of notable liturgical preachers, among them Fleming Rutledge and Hans Urs von Balthasar. It was particularly in Rutledge’s The Undoing of Death where I saw this model most clearly. Her sermons rely chiefly on scripture, but they engage the listener through means of narrative, both the newspaper narratives of Barth as well as through the use of story. To this she adds liturgical reflection. She often makes sense of the season or day wondering why the movements of the lectionary and the Church Calendar inform the way in which we hear a scripture. Sometimes she simply engages formulations from the Book of Common Prayer or words of a hymn in order to advance an idea.

Outside the liturgical tradition, we see how scripture, news, and story are crafted together in sermons that do not usually include liturgical reflection. An excellent example is Paul Scott Wilson’s The Four Pages of the Sermon,[27] where he moves from scripture to narrative, again to scripture, and finally to another narrative form. Walter Bruggemann, as another example, follows the lectionary closely and helps his listener understand the scriptures with news or narrative, but he usually stops short of liturgical exploration. Such preachers are helpful in our quest for excellent liturgical preaching, though we rely on them for assistance in engaging scripture and narrative, with additional liturgical reflection still necessary.

The Three-Legged Stool: Scripture, Narrative, and Liturgical Reflection

Paul Avis suggests that all things in the Anglican tradition rely on an “essence of synthesis.” Synthesis “stands for ‘the love of balance, restraint, moderation, measure’ (P.E.More),” while also invoking, “vision, passion, and risk.”[28] A hallmark of my own liturgical tradition, I suggest we should see synthesis as a tool in articulating multiple componants in a single sermon. Synthesis allows for balance in the face of risk, and it allows for passion in the face of restraint. Synthesis is at the heart of this model of preaching.

The first leg of liturgical preaching is based on scripture. Susan Karen Hedahl calls it, “…the ancient intermediary of preaching: scriptural texts. It is this cache of words that bears most preaching. It is the collection of writings that inescapably sits at the heart of all homiletical meaning-making, explicitly or implicitly.”[29] Scripture drives the Liturgy of the Word and leads to the sermon, which means that scripture is a part of any sermon, whether referenced directly or not. Like the questions asked at a Seder dinner, scripture is read so that the preacher and congregation may ask, what does this mean?”

The first leg of liturgical preaching is based on scripture. Susan Karen Hedahl calls it, “…the ancient intermediary of preaching: scriptural texts. It is this cache of words that bears most preaching. It is the collection of writings that inescapably sits at the heart of all homiletical meaning-making, explicitly or implicitly.”[29] Scripture drives the Liturgy of the Word and leads to the sermon, which means that scripture is a part of any sermon, whether referenced directly or not. Like the questions asked at a Seder dinner, scripture is read so that the preacher and congregation may ask, what does this mean?”

Scripture is the heritage of those in the liturgical tradition, but it is also present whether we acknowledge it or not. Beginning with scripture does not mean that a sermon has to be “bible-based,” using the language of modern evangelicals, but appreciating that it is always present. There are occasions when a liturgical preacher will rely very subtly on the scriptures of the day. There are also reasons for differentiating the voice of a liturgical preacher from the ways in which other traditions use scripture.

The second leg of the stool is narrative, which we can separate into newspaper and story narrative. Both bring the stories of human life into the sacred space of worship, though they do this differently. Newspaper narrative, following the language of Barth, suggests making sense of current events and issues on the minds and hearts of parishioners. Story narrative expresses human experience. It tells the story of a person nearby or holds up the life of one separated by time or space. Including both of these is also an act of engagement: the pews are full of stories.

The second leg of the stool is narrative, which we can separate into newspaper and story narrative. Both bring the stories of human life into the sacred space of worship, though they do this differently. Newspaper narrative, following the language of Barth, suggests making sense of current events and issues on the minds and hearts of parishioners. Story narrative expresses human experience. It tells the story of a person nearby or holds up the life of one separated by time or space. Including both of these is also an act of engagement: the pews are full of stories.

Guerric DeBona writes, “Narrational preaching is not simply a matter of telling this story and that … a homily that weaves a narrative plot that exalts God’s wonderful works in human history and connects this divine activity with everyday life already suggests that a story is at work in the lives of men and women.”[30] Mary Catherine Hilkert writes, “Part of the power of narrative preaching derives from the insight that life’s most powerful experiences can be shared only in and through personal testimony. Hearing the story of human pain or rejoicing gives access to an experience where abstract description and analysis fails. Precisely because of this ability of stories to communicate experiences that exceed the boundaries of other human language, many would claim today that narrative is the most appropriate, even the necessary category for the holy within the limits of human experience.“[31] With this in hand, we can extend narrative to include more than just news and stories, but also metaphor, satire and poetry. Roger Spillers, on the Executive Board of the College of Preachers, encourages preachers to pair the scripture with “the artistic idiom of story, song, praise as well as satire and mockery.”[32] Bruggemann encourages the use of poetry “that speaks against a prose world.”[33] They remind us that narrative in a sermon has many faces and can be engaged in many ways.

One final point is that narrative can be the driving force of a sermon, or it can be made up of vignettes that undergird a point. The kind of narrative offered will often determine how and when it is engaged. John Claypool often set the stage of his sermons by introducing a longer narrative, one to which he returned multiple times in order to make meaning. Fred Craddock, by contrast, mastered the use of short narratives, often gathered toward the end of a sermon in order to reinforce his point. Andreas Egli identifies four different types of story-telling: extremely short narrative points, short narratives, longer narratives, and extremely long narratives.[34] Each, he says, function differently and must be used differently. The shorter the narrative, as in the case of Craddock’s vignettes, the more the sermon must already make the theological point, and the narrative can only bring a thought or story to mind. An extremely long narrative, by contrast, can be the driving point of the sermon. This was true for Claypool’s art, and Egli reminds us that such longer narratives can be broken up in order to make sense of each facet thereof.[35]

The final leg of the stool is liturgical reflection. This consists of three elements: reflection on the sacrament celebrated, making sense of the calendar or lectionary, and the use of liturgical language to give life to the sermon. In Fulfilled in Your Hearing: the Homily in the Sunday Assembly, the National Catholic Conference of Bishops’ offers a helpful definition: “The Preacher’s purpose will be to turn to these Scriptures to interpret people’s lives in such a way that they will be able to celebrate Eucharist—or be reconciled with God and with one another; or be baptized into the Body of Christ, depending on the particular liturgy that is being celebrated.”[36] That is the first goal of liturgical reflection: to enable those listening to worship fully at the particular liturgy of the day.

A second goal of liturgical reflection is to make sense of the day or season, or how the scriptures relate to the broader movements of the church. In a practical way, we might admit that we use liturgical words like Advent, Transfiguration, or Ordinary Time in ways that assume more knowledge than is actually present. Encounter with the liturgical calendar is normative in liturgical traditions, but so often the prayers, scriptures, and hymns point to a liturgical reality that a sermon must clarify. It is not enough to say that Advent is about waiting, but rather to understand that claim, both for someone familiar with it and for someone unfamiliar with it. In a similar way, the lectionary crafts the delivery of scriptures across the liturgical year, but sometimes it is incumbent on the preacher to make sense of the flow. This also allows the preacher to make sense of the larger narrative of scripture, by reminding the listeners of what was heard last week, or by anticipating the direction in which the scriptures will go.

The final means of liturgical reflection is found in employing the liturgy outside of its prescribed place. Using words and phrases from baptism, Eucharist, burial, or from the collects and prayers, offers a poetic means of liturgical cross-pollination. Another advantage of sermons that incorporate liturgy is that the liturgy helps them resist becoming too distant or stale. By considering phrases of the liturgy in a sermon, the preacher protects the liturgy from becoming what Bonhoeffer calls “cultic language.”[37] A willingness to utilize these words in the sermon—spoken, with reflection, and perhaps thereby giving new meaning—allows them to operate as a homiletical device. This also enables new reflection upon them, once the sermon is finished, when they are met in the liturgy.

Project and Conclusions

The heart of my work looked at sermons of Fleming Rutledge and Hans Urs von Balthasar to see how they synthesized scripture, narrative, and liturgical reflection. In an act of emulating them (and other great preachers), I composed and preached seven sermons with this model in mind.

In reflecting on liturgical preaching as someone who engages this task weekly, I am constantly pursuing ways to engage people. This model expands the number of resources available to a preacher. By including prayers of the liturgy and liturgical experience, the preacher gains valuable resources in preparing for a sermon. The preacher also frees the words of the liturgy, beyond keeping them from becoming cultic language, but helping the listener to engage them differently and perhaps in an unexpected, generative way. Preaching in this way also allows the liturgist to announce and articulate what the liturgy intends to do, seldom a goal of preaching but important in pastoral ministry.

In the short time that I have preached, I have witnessed firsthand changes in culture that challenge the pews and pulpits of churches. I have looked to excellent preachers to discover helpful tools and patterns, and it is here that I am persuaded that the three-legged stool I suggest replicates excellent preaching in a way that might engage a changing demographic. Excellence in preaching does not end with the preacher, so success must also consider how well those listening were incorporated in the wider liturgical action. Parishioners bring with them varying levels of familiarity with the stories and practices of Christianity, and a model based on synthesis allows people to connect with elements of worship in different ways. Including various points of contact in homiletics increases the opportunity to connect with the listener, which must always be a goal of preaching. It is here that this model allows for new and different ways of engaging listeners.

Beyond the development and exploration of this model per se, I began to sense a need for projects that explore new models of preaching. Karl Barth may not be relevant forever. Tom Long suspects that narrative preaching is dying, or that it will have to change to survive.[1] Churches are undergoing rapid change, and new and renewed forms of homiletics will need to be discovered, critiqued, and improved. Preaching must continue to explore and evolve in order to do what it has always done, to welcome people more closely into relationship with the divine.

In the implementation of the project, I discovered unexpected elements that were both positive and negative. Relying on sermons that were made up of scripture, narrative, and liturgy, I found myself able to approach and articulate subjects that might otherwise have been too political or provocative. This was especially true in the sermon preached after the events in Charlottesville, Virginia. Many liturgical preachers have felt relief when the appointed lections reflect their own intentions, thereby giving some cover for what is said. The words of the liturgy also function in this way, and they can be engaged to help with this task more directly than just waiting for them in the liturgical flow. This was not without its problems. The intention of including liturgical reflection was at times the most tedious, and it often came with unintended consequences, as happened with the theme of Advent that seemed to go on forever. On the whole, however, the positive points of discovery engendered homiletically Paul Avis’ suggestion that synthesis offers balance and restraint as well as passion and risk.[2]

Future reflection will allow space to identify other positive and negative experiences of using this three-legged stool. One unexplored item is the issue of context, as all seven sermons were preached in the same parish with its own set of assumptions and common life. It is of particular interest whether or not this model could be used successfully in a liturgical context that does not readily identify as High Church or Anglo-Catholic. So many references to the Book of Common Prayer and the liturgical calendar were easily received in this context. I suspect a preacher in a different liturgical tradition might not implement this model as easily.

This project focused primarily on the composition and delivery of sermons, and future work should engage their reception on the part of those who listened. Though much thought is given to the various people who sit in the pews to listen to sermons, this project did not focus on evaluating their reactions comprehensively. Future work should be devoted to finding people who represent various levels of familiarity with Christianity, and then discerning whether or not this approach was helpful in allowing them to hear things on different levels.

In the end I was reminded of what Engemann writes in his introduction to preaching. The point of a sermon is not to be “a presentation about Jesus’ eating with tax collectors and sinners,” but it is “anhand eines Themas,” the means by which we make the story plausible enough to invite us to the same table 2,000 years later.[3] I believe this is the goal of preaching with scripture, narrative, and liturgy in mind. Sacraments bring grace to the lives of people, and sacramental or liturgical preaching brings people closer to those means of grace.

[1] Matthew 28, the Great Commission.

[2] Eugene Sutton, “The Two Calls,” accessed March 7, 2018, https://sedangli.wordpress.com/2014/06/24/decently-writ-xvii-a-sermon-by-the-rt-rev-eugene-taylor-sutton/. Citing Matt. 28:16, Sutton calls for the Episcopal Church to focus on the legacy of worship in the Anglican tradition, which has been overshadowed as of late by cultural wars.

[4] Fred Craddock, Overhearing the Gospel: Preaching and Teaching the Faith to Persons Who Have Already Heard (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978), 9-10.

[5] Thomas G. Long, Preaching from Memory to Hope (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2009), 9.

[6] Paul Scott Wilson, “Biblical Studies and Preaching,” in Preaching as a Theological Task:

World, Gospel, Scripture, edited by Thomas G. Long and Edward Farley (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 146.

[7] Don Saliers, “Worship,” in Miller- McLemore Companion to Practical Theology (Maulden, MA: John Wiley and Sons, 2014), 289.

[8] Augustine, De doctrina Christina, Book IV.

[9] This is not an imagined scenario, but was the subject of an entire sermon I heard while visiting a historical Episcopal church in Boston. That sermon was a catalyst for this project.

[10] Robert Waznak, S.S., An Introduction to the Homily (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1998), 18.

[12] Todd Townshend, The Sacramentality of Preaching (New York: Peter Lang, 2009), 21.

[13] Reginald H. Fuller, What is Liturgical Preaching? (London: SCM Press, 1957), 52.

[17] Wilfried Engemann, Einfuehrung in die Homiletik (Tuebingen und Basil: A. Franke Verlag, 2002), 399-400. Author’s translation.

[19] John Baldovin, S.J., “The Nature and Function of the Liturgical Homily,” The Way: Supplement (Spring, 1990): 93-94.

[21] Fred Craddock, “The Gospel of God,” in Thomas G. Long and Edward Farley, eds., Preaching as a Theological Task: World, Gospel, Scripture (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 78.

[22] Rowan Williams, “Archbishop: My successor needs a newspaper in one hand and a Bible in the other,” accessed March 5, 2018, http://rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org/articles.php/2686/archbishop-my-successor-needs-a-newspaper-in-one-hand-and-a-bible-in-the-other.

[23] Karl Barth, The Preaching of the Gospel (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1963), 12.

[25] Paul Scott Wilson, “Biblical Studies and Preaching,” in Long and Farley, 146.

[26] Darrell W. Johnson, The Glory of Preaching (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 2009), 103.

[27] Paul Scott Wilson, The Four Pages of the Sermon (Abingdon: Nashville, 1999).

[28] Paul Avis, The Identity of Anglicanism (London: T&T Clark, 2007), 28-9.

[29] Susan Karen Hedahl, “All the King’s Men: Constructing Homiletical Meaning,” in Long and Farley.

[30] Guerric DeBona, OSB, Fulfilled in our Hearing: History and Method of Christian Preaching (New York: Paulist Press, 2005), 102.

[31] Mary Catherine Hilkert, Naming Grace: Preaching and the Sacrimental Imagination (New York: Continuum, 1997), 96-97.

[32] Roger Spiller, “Preaching and Liturgy: An Anglican Perspective,” in The Future of Preaching, ed. Geoffrey Stevenson (London: SCM Press, 2010), 38. Here Spiller is referencing Bruggemann, Finally Comes the Poet, 1989. Spiller consolidates Bruggemann’s ideas, encouraging preachers to “reengage the prevailing worldview.”

[33] Walter Bruggemann, Finally Comes the Poet (Mineapolis: Fortress, 1989), 3. Here, Bruggemann uses the ideas of poet more liberally than I am using them, though he does suggest the crafting of words and ideas in more poetic ways that help to engage and move the listener.

[34] Andreas Egli, Erzaehlung in der Predigt: Untersuchung zu Form und Leistungsfaehigkeit erzaehlender Sprache in der Predigt (Zuerich: Theologischer Verlag, 1995), 107 ff, author’s translation. Egli identifies extremely short narrative points as having 1-2 sentences, short narratives as having 3-8 sentences, long narratives as having 9-32 sentences, and extremely long narratives as having 33-128 sentences.

[35] Egli, 111. By his math, a narrative with 65 or more sentences must be broken up in order to make sense. His observations in the book are derived from recordings of Swiss radio preaching.

[36] Waznak, An Introduction to the Homily, 13-14.

[37] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Worldly Preaching: Lectures on Homiletics, edited and translated by Clyde E. Fant (New York: Crossroad, 1991), 140.