“When Mary is greeted by the angel Gabriel, where is she and what is she doing? How do you imagine her?”

I posed these questions to the students, after we had read through the story of the Annunciation in Luke 1:26-56, during the third week of Sunday school class entitled, “Reading the Bible with Rembrandt.” None of the thirty or so adult learners had a response. Then, we looked at visual interpretations of the story by a variety of artists. In Henry Ossawa Tanner’s painting, Mary sits on her bed as if she has just been woken from sleep.[1] She is wrapped in a robe, her hands clasped in front of her in a gesture of nervous uncertainty. The angel is not a human form but a pillar of light. Participants in the class noticed that the rug was wrinkled and the bed unmade. Mary has been surprised, maybe even awoken, in an ordinary moment in her life. Perhaps, the students suggested, Mary is trying to figure out if she is still dreaming. They notice that Mary is not wearing her signature blue color; instead, the blue robe lies off to the side, as if she has not decided yet whether to put on the mantle of the mother of God. Some participants noted that it had not occurred to them when they read the text that Mary had made any kind of decision in the situation, that there might have been a moment when she hesitated. They noted that the angel doesn’t look like a typical angel; perhaps, they wonder, we need to be on the lookout for angels in forms we do not expect.

William Congdon, Annunciazione (1960), oil on masonite – cm. 145×130 © The William G. Congdon Foundation, Milan.

In William Congdon’s interpretation, Mary is featureless; she sits unmoving and wrapped in blue, as an abstract spirit, part angel and part bird, overshadows her, diving directly towards her abdomen.[2] In this image the powerful movement of God is highlighted; the angel/Holy Spirit takes up much of the image and the bright white of its wings and body contrast sharply with the muted colors of Mary and everything else. More than one participant said after viewing these images that they had not previously noticed in the text the presence, power, and movement of the Holy Spirit.

There is a demur saintliness of Mary in Botticelli’s painting, as she sits dutifully reading Scripture and the angel kneels before her, holding a lily to signify Mary’s purity.[3] Mary is the right person to be chosen by God. She is already bathed in blue and her eyes reveal her humility as she looks not up or at the viewer or at the angel, but at the floor. She is good, humble, and faithful; she believes in God’s promises, and for that she is rightly to be admired and imitated.

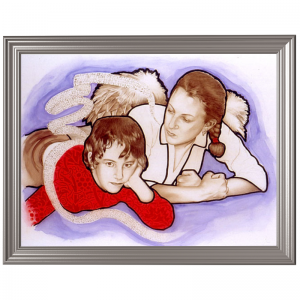

Contrast that depiction with the barely pubescent Mary in Jennifer Linton’s Annunciation.[4] She looks impossibly young to be taking on the task given to her. She doesn’t look humble or regal or even surprised by the angel speaking to her. She looks like an ordinary teenager. Unlike all the other Marys, she stares out of the painting, out at the world we live in, inviting us into the story or, conversely, challenging our assumptions about her.

After viewing this painting, participants said they had not considered how young Mary was, or that she might have had some of the emotions we so often associate with teenagers. Those were just some of the interpretative insights from a single class that placed works of art in conversation with a biblical text.

How do we read the Bible and understand its meaning?

This is not an easy question to answer. Over the course of my Doctor of Ministry work at Candler, I asked members of two different Presbyterian Church (PCUSA) congregations this question, and received many different answers. Some read the Bible as they were taught to read growing up in a church (but not necessarily a Presbyterian church), or by parents or grandparents. Some told me they were only taught to read the Bible literally. Some said that they were never told to read the Bible literally. Some still read the first Bible they were ever given. Some read from as many translations as they can get their hands on. How we read the Bible and understand its meaning matters to how the community of faith understands the Bible as Scripture, and how we understand the authority of the Bible. [5] The two large, historic Presbyterian churches had members from a number of religious backgrounds, and were formed in reading the Bible in innumerably different ways.

What would be a means for members of the same church who read the Bible in different ways to learn from one another’s perspectives in a way that felt safe and enriching?

What would be a way, through Christian education, to broaden an individual’s understanding of biblical interpretation?

And, what would help open our eyes to new ways of reading the text?

Art seemed like a possible answer to these questions.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael, 1637, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Visual depictions of the biblical stories have been around since the beginning. These were used as decoration or illustration, or as a way to teach the stories to the illiterate. But as time went on, artists came to do more than just illustrate. They brought into focus the emotions of characters. They imagined scenes only minimally described in the biblical text. They filled in gaps in the stories or highlighted details we might pay little attention to. They revealed meaning through color and shapes, through light and dark, through figures and symbols. In short, they exegeted the Bible in the paintings, drawings, and sculptures they created. Recently, this has been called “visual exegesis,” [6] or more specifically “graphic exegesis” when referring to a produced work of art. [7] Until recently, these glorious and instructive works of graphic exegesis were relatively inaccessible to the local church classroom. More and more, good quality digital images are available online. Museums are giving digital access to their collections and permission to use images in educational settings. Many images are available in the public domain or under public use copyrights. Contemporary artists have social media accounts, emails, and websites, and can be contacted for permission to use their work for non-commercial purposes.

George Segal. Abraham’s Farewell to Ishmael, 1987. Painted plaster. 107 x 54 x 54 inches. Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, gift of The George and Helen Segal Foundation, Inc. © Pérez Art Museum Miami. Photo: Oriol Tarridas. Photo: Lisa Morales.

Laptops, projectors, smart TVs, and color copiers are becoming ubiquitous and less expensive, making it easier to use images in a local church setting. Scholars are writing excellent reflections on particular works of art as exegesis. Thankfully, a Christian educator does not have to be an artist or an art historian to use art in education.

Art is beneficial in Christian education in a number of ways. A handful of excellent paintings can reveal in a brief time what might take hours with several commentaries, and introduces students to the possibility of interpretation in forms other than sermons and written sources. Art helps us to see what we might have overlooked in our previous readings of Scripture; artists explore gaps we rushed over or expand details we failed to notice. Graphic exegesis benefits those who are visual learners and highlights the visual nature of the Bible. Students may find great value in learning how the Bible has been interpreted by individuals in other times and cultures.

Graphic exegesis can generate conversations around interpretation in diverse communities of faith, creating a mindful and creative means to explore the interpretative terrain beyond a single, plain reading of a text. A work of art represents an interpretative reading of a text, which itself can be interpreted in multiple ways by different viewers, and these perspectives can be brought into conversation with different readings of the text. Art creates a safe space for conversations around meaning; while it is perhaps easy to say that someone is wrong in how they read a text, it is more challenging to say someone is wrong in how they “read” a painting. Graphic exegesis engages the imagination in such a way that the reader is nurtured and formed by their study; aided by imagination, we enter the “worlds of possible meaning” of the story, thereby “opening oneself to the new possibilities of meaning offered by these texts, realizing this meaning within oneself, and being transformed by this realization.” [8]

Reading the Bible with Rembrandt

At First Presbyterian Church in New Bern, North Carolina, I offered a four-week class entitled “Reading the Bible with Rembrandt” that engaged in conversation with texts and images. [9] In the first class, students learned how to read a religious image. This turned out to be vitally important so that the class was not side-tracked by how similar or dissimilar the image was to the text, or whether they liked it or not, and instead focused on the elements that made up the artist’s interpretation. In each class we looked closely at the text and then at several visual interpretations, and then returned to the text to see what insights we had gained. Throughout, participants shared what they noticed in the text and what they noticed in the images. At the end of each class, students were asked to reflect on what they had learned from the text, the images, and each other. In the initial survey completed by class members, only a handful of people remarked on the need for other people’s perspectives when interpreting a text. In the final survey, almost every participant made some mention of how their understanding of interpretation had changed and how important it was to hear how other people interpreted the texts and paintings.

[The class method] made me more aware of the different views people have while looking at the same thing. This was valuable to me in that it shows how varied peoples’ interpretations of the Bible can be and how many different views must be evaluated to reach your own conclusions.– Class Participant

The overall feedback from participants was enthusiastic. More than once a participant noted that the conversation around the art sent them back to the text for further study and made them want to study the Bible more. One participant wrote, “Each image makes me want to go back and read the passage again with that visual in mind.” Another wrote, “The emotions and postures depicted in the painting were so powerful and revealing. After the class, I revisited the biblical scriptures about Hagar and Ishmael and had a better understanding of the relationships.” And, more than one participant stated that they will continue to use art in conversation with Scripture for their own spiritual growth and learning: “What worked about the class method is that the class combined art, Scripture, and dialogue. I loved the different perspectives from our classmates. I gained knowledge in how to read art. I loved the handouts and the art pieces that were shared. I have planned a trip with a friend to go view art that responds to Scripture.” One participant mentioned that the positive aspects of the method were that it was “intellectually stimulating, relaxing, there were opportunities to examine/question Scripture, connection to the past” and then she added, “I liked having permission to stop and think (visualize) the story instead of rushing to find meaning.”

I have a new found respect for the art created based off the Bible. I had not really given much thought to it but now I see it completely different. Talking through it together helped me to understand the story better and remember it better and ultimately improve my faith.

– Class Participant

Visual/Verbal Method

Visual/Verbal Method

Even though my Doctor of Ministry project is completed, I continue to incorporate images into my teaching on Sunday mornings, and I do this for several reasons. This “visual/verbal method” (as one participant dubbed it) proved to be remarkably effective. A number of people commented on how the images helped them learn and better remember the stories. There are many ways of learning and a number of people benefit from a visual component to learning, but Sunday school offerings tend to rely on written resources or lectures. Throughout the class, the adult learners saw things in the text that they had not seen before. The text came alive for them. People who felt like they didn’t know enough to speak up in class, felt comfortable sharing what they observed in an image; using images, I found, allowed for greater participation. And perhaps the greatest benefit is that a painting is an interpretation, but then each person who views a painting interprets the painting differently, analogous to how each person reads a text a little differently. Graphic exegesis demonstrates that more than one interpretation of a text doesn’t diminish the biblical text, but instead expands and enhances the meaning.

In summary, there is tremendous value to the interpretation of the artist as well as the interpretation made by the person sitting next to us in the pew.

In featured image: Rembrandt van Rijn, Dismissal of Hagar and Ishmael, 1640-43, The British Museum of London.

[1] Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1898, Philadelphia Museum of Art, accessed March 18, 2019, https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104384.html.

[2] William Congdon, Annunciazione, 1960, The William G. Congdon Foundation, Milan.

[3] Sandro Botticelli, Annunciation, 1489, Uffizi, Florence, accessed March 18, 2019, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/annunciation-d9604d56-89bb-414c-ba3c-fd71f4d28eec.

[4] Jennifer Linton, The Annunciation, 2002, accessed March 18, 2019, http://www.lilithgallery.com/gallery/images/annunciation-jenniferlinton-2002.jpg.

[5] Ellen Davis, “Holy Preaching: Ethical Interpretation and the Practical Imagination,” in Ellen F. Davis and Austin McIver Dennis, Preaching the Luminous Word: Biblical Sermons and Homiletical Essays (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2016), 90: “The essential form of the common life is in the broadest sense a conversation in which members of the community explore and debate the meaning of their sacred texts and find ways to live together in accordance with what they have read.”

[6] Paolo Berdini, The Religious Art of Jacopo Bassano: Painting as Visual Exegesis, Cambridge Studies in New Art History and Criticism (Cambridge, England; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997). Berdini develops the concept of visual exegesis arguing that a reading of a text necessitates a kind of expansion, which is also present when a text is visualized by an artist.

[7] Christopher Nygren, “Reflections on the Difficulty of Talking about Biblical Images, Pictures, and Texts,” in The Art of Visual Exegesis: Rhetoric, Texts, Images, eds. Vernon K. Robbins, Walter S. Melion, and Roy R. Jeal, Emory Studies in Early Christianity, Vol. 19 (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2017), 288. The word graphic “is used simply to underline the concrete, manufactured nature of the object” (289).

[8] Douglas Burton-Christie, The Word in the Desert Scripture and the Quest for Holiness in Early Christian Monasticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 299. Burton-Christie describes how the early desert mothers and fathers “saw the sacred texts as projecting worlds of possible meaning that they were called upon to enter. To ruminate on Scripture was to embark upon a deeply personal drama that the monks referred to as the quest for purity of heart. Interpretation of Scripture in this context meant allowing the text to strip away the accumulated layers of self-deception, self-hatred, fear, and insecurity that were exposed in the desert solitude and in the tension of human interaction. It also meant opening oneself to the new possibilities of meaning offered by these texts, realizing this meaning within oneself, and being transformed by this realization.”

[9] I am indebted to Amanda Benckhuysen’s article for the title of this project and the class. See Amanda W Benckhuysen, “Reading the Bible with Rembrandt: A Fresh Look at Bathsheba in 2 Samuel 11,” Calvin Theological Journal 50, no. 2 (November 2015).