The Project

Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Nashville, Tennessee is launching the Dream Center Project, an ambitious effort to build affordable rental housing in North Nashville, while simultaneously initiating economic and community development in the area around our inner-city Historic Jefferson Street location. It is a faith-based, asset-based community development project. Although many gains were won during the civil rights movement, as will be discussed herein, abundant living in community, the type of living God wants all to have, remains out of reach for many people of color. Many of the same issues that were impetus for the movement, such as inequality, the lack of decent, affordable housing and economic viability, continue to exist and must be addressed. This project assesses the continuing problems and the role of the church, and describes how Mt. Zion is addressing those needs with this project. Using the property in this manner will provide a sustainable resource that can operate in perpetuity for the benefit of the community.1

The featured image above depicts the Historic Jefferson Street location in the bottom right-hand corner with a background of recently constructed “Tall Skinny” housing, the symbol of gentrification and lack of affordable housing in Nashville, in the Buena Vista neighborhood where the church is located. The tall skinnies are next to an older home that has so far escaped demolition.

Towering above the housing is the downtown skyline, with the tallest being one of the largest residential buildings in the city, 505 Condos. 505 is another monumental example of Nashville’s affordable housing crisis. The church is depicted smaller than the background neighborhood because the issues being addressed with the project are bigger than the church. So, the church is moving outside its walls out into the community at large to make a difference.

Why The Dream Center?

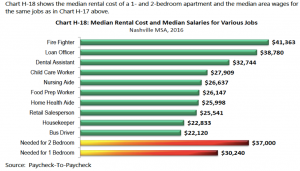

There is an affordable housing crisis in Nashville to the extent that even people who have working class level income, nurses, teachers, firefighters, loan officers, postal workers, police officers and dental assistants, people who go to work every day, cannot afford housing in many areas of Nashville. This crisis is especially acute in the rapidly gentrifying sections of the city. In addition, over 50 years after the civil rights movement opened up opportunity for people of color, the race gap continues to persist, and the problems of income inequity, poverty, health, housing, unemployment, and mass incarceration continue to negatively impact the African American community.

Thus, the lack of affordable housing and income inequality is especially traumatic for the African American Community. The need to address these chronic issues is the impetus for the project. The affordable housing component of the Dream Center, and the business/office components, will address some of these issues in North Nashville, where the Dream Center will be located. The Dream Center will also be an evangelistic endeavor that will meet the demands of changing ministry dynamics, through an out of the box ministry designed to meet the needs of a growing church congregation and a rapidly growing and changing Nashville community.

The Dream Center Project

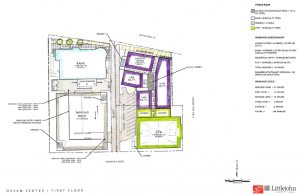

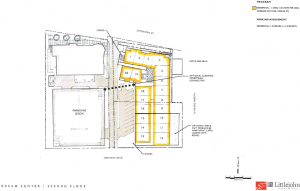

The Dream Center project is a multi-million dollar three building mixed-use development project that incorporates housing, fitness, outreach, and commercial spaces. It will be built on church-owned property located in the inner-city, directly across Jefferson Street from the church. In the current plans, Building 1 when completed will be 6 stories, and include 106 residential rental units, small business office/retail space, church offices, and a high school sized gymnasium, Building 2, an office building, will house the local African-American owned bank’s headquarters, and the Nashville Business Incubation Center (NBIC). Building 3 will be a 3-level parking garage.

Dream Center Floorplans

The floor plans show the layout of the development.

Frank Stanton Developers

It will be built on three lots totaling 1.78 acres that the church purchased in 1989 across Jefferson Street from a member family that once owned a printing company on the site. A satellite view shows the property in the highlighted area just south of the Mt. Zion Historic Jefferson Street Location, across Jefferson Street, and also bounded by 11th Avenue, North, Meharry Boulevard, and the I-40/I-65 North Loop Freeway and interchange.

The image below shows the lot where the Dream Center will be built directly across from the church in the shadow of downtown.

A view down Jefferson Street from the church shows the ubiquitous liquor store.

The “It City”

Called the “It City” by a 2013 New York Times article, Nashville has low overall unemployment, but its black community still faces high unemployment, crime concerns, and worsening poverty.2 Rising housing costs push or keep black people out of middle class neighborhoods and a black underclass exists.3 “The ‘It City’ boom has brought significantly more wealth to Nashville, but it has not been shared across the region. In fact, in the past three years, the difference between the haves and the have-nots in Music City has only gotten larger.”4 The top 20% of Greater Nashville’s wealthiest areas holds 48.81% of the region’s net worth. This is almost six times more than the bottom 20%.5

Research Process

Data compiled by Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, a city agency, from 2015 through 2017 was reviewed and analyzed. Metro Social Services does extensive annual compilation and analyses of the socioeconomic characteristics, demographics, dynamics, community needs, and disparities of Nashville-Davidson County residents, including income, poverty, race, food and nutrition, health and healthcare, housing, unemployment, incarceration, wages, and wealth.

The data also measures how the city has progressed over time in addressing these concerns. This information provides guidance for local leaders, policymakers, and stakeholders in improving the lives of Nashvillians. A wealth of information was obtained from the Social Services data.

The data also measures how the city has progressed over time in addressing these concerns. This information provides guidance for local leaders, policymakers, and stakeholders in improving the lives of Nashvillians. A wealth of information was obtained from the Social Services data.

The Nashville Tennessean newspaper has been running various series on Nashville’s affordable housing crisis. Informative data was obtained from Tennessean articles on this issue, especially articles by opinion writer David Plazas, who has been closely following, conducting research, and comprehensively writing on this issue. Data was also obtained from other Tennessean reporting on such issues as racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Other local publications from which local data and other information was obtained includes the Nashville Business Journal and Gideon’s Army, Driving While Black: A Report on Racial Profiling in Metro Nashville Police Department Traffic Stops.

Also instrumental was Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. It does a great job of looking at the history of racial discrimination in America leading up the current situation involving systemic use of the criminal justice system as a means of social control and oppression regarding people of color.

In forming the plans for the Dream Center, the Mt. Zion Board of Directors began exploring development of the subject property following the leading of the Holy Spirit, with the goal of advancing economic and community development, without initiating a church building fund drive to finance the development.

I was appointed to a newly formed Finance Committee to handle the legal matters. The committee’s purpose is to review the project’s financial projections, the Church’s financial capacity, proposed capital and lending structures, the legal and tax structure and considerations, and advise the full Board on recommendations regarding the project. I met with the church’s chief financial officer and outside legal counsel retained for project consideration several times regarding formation of the project. After detailed consideration of the Dream Center’s ownership and legal structure, capital structure, projected cash flow and reserves, demand for similar housing, and TIF financing, upon the committee’s recommendation, the Board voted to proceed with the project.

A new entity would be formed as a community development corporation (CDC). CDC’s are tax-exempt, not-for-profit organizations authorized by Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3). The 501(c)(3) is the preferred method for structuring this type of organization. It has the advantages of providing community benefits with limited liability to the founding organization. That is, any liability that the CDC may incur is limited to the CDC and the assets of that CDC. Black church affiliated CDCs, as opposed to electoral participation, are a major strategy used by urban Blacks to alter the physical and economic conditions of their communities.6 Mt. Zion also has previous experience with the CDC organization. The New Level CDC was formed several years ago to provide homebuying assistance to first-time homebuyers. The new CDC will be separate from New Level.

A new entity would be formed as a community development corporation (CDC). CDC’s are tax-exempt, not-for-profit organizations authorized by Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3). The 501(c)(3) is the preferred method for structuring this type of organization. It has the advantages of providing community benefits with limited liability to the founding organization. That is, any liability that the CDC may incur is limited to the CDC and the assets of that CDC. Black church affiliated CDCs, as opposed to electoral participation, are a major strategy used by urban Blacks to alter the physical and economic conditions of their communities.6 Mt. Zion also has previous experience with the CDC organization. The New Level CDC was formed several years ago to provide homebuying assistance to first-time homebuyers. The new CDC will be separate from New Level.

Summary of Findings

Lack of Affordable Housing

Nashville’s development boom has made housing costs skyrocket, causing the dwindling supply of available housing for teachers and other crucial sectors of the workforce, as acknowledged by city leaders.7 In April 2019, average apartment rent in Nashville is $1,310 for studios, $1,271 for one bedroom, $1,422 for two bedrooms, and $1,583 for three bedrooms. This is a 2.6% increase in the past year.8

With its rapid growth and influx of new Nashvillians, the city suffers from a severe lack of affordable housing. At current growth rates, Nashville is estimated to need 31,000 additional affordable rental units over and above the projected available units by 2025.9

Housing is affordable when the homeowner or tenant spends no more than 30% of his or her income on it. Spending more than 30% makes someone “cost burdened.” In Nashville, affordable is when rent does not exceed 30% of the income of a household earning less than 60% of the Davidson County Median Income.10 In 2018, the median household income (MHI) for Davidson County was $54,855. 60% of that is $32,913, which means that rent is affordable if it does not exceed $822.25 a month, including utilities. Census tract data shows that there are cost burdened renters all across Davidson County.11 The 2-bedroom rental unit (minimum) Housing Wage for the Nashville MSA, the amount that a household must earn working 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year, to afford the Fair Market Rent of $925, without paying more than 30% of their income, was $17.79. At these rates, a person would have to work 2.5 minimum wage jobs to afford housing.12

The above local study looks at the median income needed to afford 1 and 2 bedroom apartments, and the median area annual wages for various low- and workforce-income jobs.13 Many of these jobs pay wages far below the amount needed for them to rent affordable housing. Only two of the ten categories, the fire fighter and the loan officer, can afford 2-bedroom apartments. Only firefighters, loan officers, and dental assistants can afford 1-bedroom apartments.

Gentrification

Comparison of census tract data shows how the poverty that was centered in the inner-city in 2000 had spread towards the outer, suburban areas of Davidson County by 2014. People with lower incomes are being pushed farther out into the county due to rising housing costs, gentrification, and the resultant migration in search of affordable housing. Nashville is one of the nation’s top 10 gentrified cities, being the 6th most gentrified city in the U.S.14 People are being displaced from historically African American neighborhoods, many from the neighborhoods where they grew up. Many of the inner-city homes are being purchased by developers, with their lots being subdivided and replaced with two or three narrower, taller homes to provide desired space, called “tall and skinnies.”

These homes are tailored for the more affluent buyers moving into the area, and are much more expensive than the ones they replace. Other homes and buildings are being replaced by more expensive apartments and condos. Many native Nashvillians from the traditionally African American neighborhoods where these new homes are being built can now no longer afford to live in the neighborhoods where they were born, raised, and now work. Providing affordable rental housing is important for African-Americans, due to their lack of homeownership. African-Americans’ rate of homeownership in Nashville, 39.1%, is significantly lower than that for Whites, 62.3%. African-Americans rent at a much higher rate, 60.9%, than the White population’s rate of 37.7%.15 This affects their ability to transfer wealth and property through equity to future generations.

North Nashville Housing Tour

Lack of Opportunity

It has been more than fifty years since the civil rights movement. Despite the passage of laws and regulations designed to grant equality to people of color, the problems of poverty, poor health, high unemployment, and crime continue to plague the African American community. Government and Non-government organizations’ (NGOs) provision of welfare and charity have not been the answer, but are merely band-aid treatment of the underlying symptoms.

The lack of opportunity for this community began with the diaspora of the transatlantic slave trade.16 The imported Africans were sold into bondage as the ideal slaves.17 The lingering effects of the bondage of slavery and subsequent ongoing systemic discrimination and oppression continue to this day. As Michelle Alexander forcefully argues, “It may be impossible to overstate the significance of race in defining the basic structure of American society.”18

Judicial Inequality – The Tyranny of Jim Crow

The end of slavery proved to be symbolic and largely illusory. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices to prevent blacks from voting were enacted.19 The southern planter elite managed “to re-establish a system of control that would ensure a low-paid, submissive labor force.”20 A new racial caste system of legal segregation developed that came to be known as Jim Crow, which operated primarily in southern and border states between 1877 and the mid-1960s.21 It was a method of social control that included violence and lynching as its staples. Laws known as “black codes” were passed to control and re-enslave freed slaves, convicting those that did not have jobs as vagrants. They were arrested by the thousands for minor offenses, petty crimes and trumped-up charges. These convicted “vagrants” were hired out to plantation owners and private businesses in another system of legal forced labor, and forced to work for little or no pay.22

Evidence of this caste system was recently located in Sugar Land, Texas, near Houston where the unmarked graves of 95 free men, women and children ensnared by this forced labor system were unearthed at a construction site. The laborers were forced to work as cheap labor on the sugar cane plantations that give the now-affluent Houston suburb its name.23

Continuing Inequities – Social Control and Mass Incarceration

Today, long after the Jim Crow era ended, “a new system of racialized social control maintains racial hierarchy much as earlier systems of control did … mass incarceration operates as a tightly networked system of laws, policies, customs, and institutions that operate collectively to ensure the subordinate status of a group defined largely by race.”24 Mass incarceration of African Americans is such an oppressive problem that it has been called “The New Jim Crow.” “African-Americans are more likely to be arrested, convicted and face stiffer sentences.”25 People of color make up 37% of the U.S. population, but are 67% of the incarcerated population.26 Mass incarceration has been devastating to the African American community. It has created tremendous problems for African Americans attempting to reenter society after they have served their sentences in employment, housing and other opportunities to improve their lives.27 Skyrocketing incarceration rates of African-Americans have contributed heavily to their chronic unemployment.28 Being Black has been so conflated with being criminal “… that white ex-offenders may actually have an easier time gaining employment than African-Americans without a criminal record.”29

Economic Inequality in Nashville

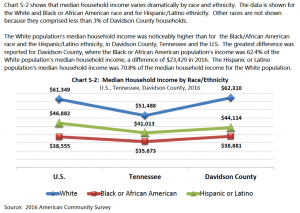

As in the rest of America, the race gap definitely exists in Nashville. The median household income race data for African American, White and Latino populations in Nashville-Davidson County and at the state and federal levels reflects the stark differences between White income and the income for people of color, which is much lower.30

In Nashville-Davidson County, people of color are far more likely to live in low and moderate income areas. Economic disenfranchisement in many cases leads to crime and inequitable law enforcement. These disparities disproportionately affect the African American community and other communities of color.

In Nashville-Davidson County, people of color are far more likely to live in low and moderate income areas. Economic disenfranchisement in many cases leads to crime and inequitable law enforcement. These disparities disproportionately affect the African American community and other communities of color.

Unequal Justice in Nashville

Judicial inequities exist in Nashville as in other communities across the U.S., from disproportionate arrest rates to draconian criminal laws and unequal imposition of prison sentences. Tennessee has some of the most burdensome felony disenfranchisement laws in the nation, which disproportionately negatively impact African Americans.31 Such inequities are and have been devastating to Nashville’s African American community. Criminal justice inequities also contribute to the economic inequality problem.

The Church Can Make a Difference  (Inside Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris)

(Inside Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris)

Mt. Zion’s foundation is the authoritative Word of God. That Word says God is a God of justice.32 Thus, by divine authority, Mt. Zion must impact social equity and justice. Luke 4:18 is a directive for the church. It is a scripture of hope, deliverance, vision and freedom. Through wisdom and discernment, Mt. Zion’s mission is to free people from oppression through economic and community development efforts. The church must help bring about economic and social equality for the nation’s African American citizens. That is the basis of this project. It is born out of a liberation theology to advocate and work for equality of civil and economic opportunity.33 This is a prophetic radicalism that focuses on the social root causes of economic inequality.34 It also means facilitating and promoting a major social impact on the laws and culture of the nation, with the goal of achieving social justice.35

(Inside Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris)

The basis of the Dream Center project is to stimulate and establish such economic power within the African American community that the overall American economic and political system would have to respect it. The Dream Center will be an economic generator for the neighborhood. We can address the need for affordable housing, meet the demands and address the changing dynamics of the church and ministry, capitalize on the growth of the Nashville market, and perform community development and outreach.

Future Implications

The Dream Center has various components, each with their own distinct purpose, goals, objectives, operations, people, controls, and outcomes. Therefore, the different components will each have a different impact. This is a project that will extend out into the long-term future. The community improvements from the Dream Center will help break down the economic walls of separation that keep people from opportunities to be productive members of society. We also hope that this will be a model not only for Mt. Zion to facilitate other such projects, but for other churches to take action and move outside their walls and get involved in economic and community development. The affordable housing provided by the development will provide people the ability to live in the community that they desire, in homes that are decent and affordable. The banking, office, retail and Business Incubation Center components will help develop the North Nashville economy and provide opportunity and jobs. The Dream Center will also evangelize to people that it is a tangible example of how Christ loves them and can provide for all their deepest needs. This project can help transform Nashville into the city, the beloved community, that God would have it to be.

1 Gary Paul Green and Anna Haines, Asset Building & Community Development (Los Angeles: Sage, 2016), 10, 13.

2 Kim Severson, “Nashville’s Latest Big Hit Could Be the City Itself,” Nytimes.com, January 01, 2013, accessed October 26, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/09/us/nashville-takes-its-turn-in-the-spotlight.html.

3 Nancy Tatom Ammerman, Arthur E. Farnsley, and Tammy Adams, Et Al., Congregation and Community (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 26.

4 Meg Garner and Carol Smith, “The ‘It City’ Boom Isn’t for Everyone,” Bizjournals.com, October 21, 2016, accessed October 28, 2016, http://www.bizjournals.com/nashville/news/2016/10/21/the-it-city-boom-isn-t-for-everyone.html.

5Ibid.

6 Drew Smith, New Day Begun African American Churches and Civic Culture in Post-civil Rights America(Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 215.

7 Sandy Mazza, “Nashville Schools Officials in Talks to Trade Land for Affordable Teacher Housing,” The Tennessean, January 14, 2019, accessed February 07, 2019, https://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2019/01/14/nashville-mnps-schools-talks-trade-land-affordable-teacher-housing/2547996002/.

8 “Local Guide,” Apartments for Rent in Nashville TN, April 01, 2019, accessed April 01, 2019, https://www.apartments.com/nashville-tn/?bb=yngz15iw2Is4h7xpoB.

9 Office of the Metropolitan Mayor, Nashville & Davidson County’s Housing Report, 2015, 2015, 17.

10 Nashville Organized for Action and Hope (NOAH), Affordable Housing and Gentrification Report, October 28, 2018, (Nashville: Nashville Organized for Action and Hope, 2018), 5.

11 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, Social and Economic Disparity in Nashville, (April 7, 2017), 69.

12 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, 2016 Community Needs Evaluation 8th Annual Edition, 2016, 164.

13 Ibid., 165.

14 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, Social and Economic Disparity in Nashville, 68.

15 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, Planning & Coordination-Social Data Analysis. 2017 Community Needs Evaluation 9th Annual Edition, 2017, 111.

16 Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2010), 23-26.

17 Ibid., 24.

18 Ibid., 25.

19 Ibid., 29-30.

20 Ibid., 30.

21David Pilgrim, “What was Jim Crow” Sept. 2000, Edited 2012, Accessed December 27, 2018. https://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/what.htm.

22Alexander, The New Jim Crow, 28.

23 Monica Rhor, “Grave Discovery Unearths Legacy of Black Convict Labor,” USA Today, 2018, December 27, 2018, accessed December 27, 2018, http://tablet.olivesoftware.com/Olive/ODN/USAToday/PrintPages.as…c=USA/2018/12/27&from=1&to=1&ts=20181227085556&uq=20181019025800 and http://tablet.olivesoftware.com/Olive/ODN/USAToday/PrintPages.as…=USA/2018/12/27&from=3&to=3&ts=20181227085556&uq=20181019025800.

24 Alexander, The New Jim Crow, 13.

25 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, Profile of Struggling People in Nashville: Release of the 9th Annual Community Needs Evaluation, (February 21, 2018), 101.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid., 102.

28 Alexander, The New Jim Crow, 216.

29 Ibid., 193.

30 Metropolitan Nashville Social Services, 2017 Community Needs Evaluation 9th Annual Edition, 2017, 36.

31 Hedy Weinberg, “Too many Tennesseans are disenfranchised. They don’t have money, they can’t vote and that’s not right. | Opinion” Tennessean.com, February 5, 2019, accessed February 20, 2019, https://www.tennessean.com/story/opinion/2019/02/05/aclu-voting-righ…enfranchisement-american-civil-liberties-union-tennessee/2779658002/.

32 Isaiah 30:18, 61:8.

33 Martin Luther King, 1967, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? In A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James Melvin Washington, 557-562. (New York: HarperOne, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2006).

34 Robert M. Franklin, Another Days Journey: Black Churches Confronting the American Crisis (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1997), 45.

35 Raphael G. Warnock, The Divided Mind of the Black Church: Theology, Piety, and Public Witness (New York, NY: NYU Press, 2014), 41.

“Tall and Skinnies”

“Tall and Skinnies” Please come along with me as we take a quick tour of North Nashville development and housing gentrification:

Please come along with me as we take a quick tour of North Nashville development and housing gentrification: