Behind, In, In Front of

A Study in Communal Hermeneutics

Introduction

Upon taking the reins as the pastor of a small United Methodist congregation in Westfield, NY, I quickly learned there was an unwritten rule that the pastor alone was to lead Bible studies. The reason? The pastor is the only one with seminary training. I cherish my theological education. However, I used that education as a springboard to read widely the Scripture and works of biblical and theological scholarship. There is no question—my seminary professors would be proud. So, with gusto I offered the congregation crash course on the Bible, specifically a manner on how one might read or study the Bible. After all, as Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart affirm, “One does not have to have a seminary education in order to understand the Bible”.[i]

The Problem

A congregational survey revealed that roughly 70% of my congregation claimed to read the Bible at least once during the week. I was alarmed that nearly 30% of my congregation indicated that they do not read the Bible. The reasons given had quite the range from unfamiliarity with the Scripture as children to not knowing what to believe, to surrendering to even try to understand the claims of Scripture.

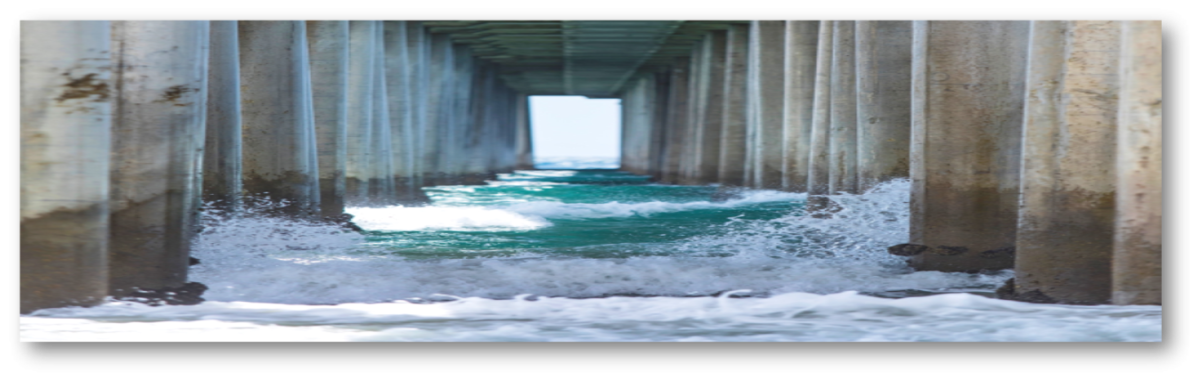

Carolyn Sharp remarks of Scripture, “just as there are countless ways to engage the ocean. There is not only one faithful way to read”.[ii] The participants in the four-week study on Genesis 1-2, have read the Bible most of their lives. However, I learned that beyond learning how to locate a passage’s coordinates (chapter and verse), they had not received training on how to read/ study the Bible. In other words, they had entered the Scripture, but they were not instructed in helpful ways of how to navigate these waters. They can sing Joy to the World or As the Deer with the best of them. But when it comes to substantive tasks of trying to understand the logic Paul uses in Romans 9-11, or to make sense of the Old Testament’s borrowing from the cultural artifacts of the Ancient Near East, my congregation was without equipment tossed by the waves.

Seminary provided me the tools to perform the tasks of exegesis (drawing from the text). It is reasonable to provide said tools to my congregation so that they might become responsible interpreters of the Scripture. Idealistically, the participants would get excited about reading the Scripture, adopt a simple method of considering the three worlds of the text: Behind, In, and In front of and revival would break across the shores of Lake Erie.[iii]

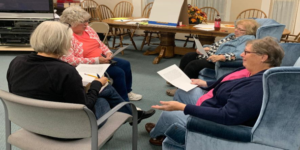

Many of the participants held biblical resources in their hands (commentaries, dictionaries, etc.) for the first time. The primary text was Genesis 1-2. The weekly conversations centered on the discoveries and the questions raised from the assigned readings and the in-class object lessons.

A major component for the written project, was to place Sharp, Fee and Stuart, and Walter Brueggemann in conversation with the participants of my four-week study. Ultimately, I will make a recommendation on the method from the biblical scholars named above, that may best meet the need of my congregation.

Behind the Text

We compared Genesis 1:1-2:4a with Genesis 2:4b-25. We noticed different ways the two creation accounts were told. The class figured that these passages were written to address two different concerns or time periods. A few suggested that these two readings may be have been written by different authors. Such a thought felt scandalous when I first learned of the Documentary Hypothesis in seminary. Such an idea is foreign in my experience in the local church. On the surface, the class was unfazed by such a notion. During this session we explored the possible historical situations of Genesis 1-2 and located references points to places in the Scripture the author(s) may been influenced by the Ancient Near East.

In the Text

The class began with biblical quotes taken out of their literary context placed in a beautified setting thanks to the wonders of PowerPoint. The class conversed about the said quotes. We slowly read Genesis 1-2, to identify the author’s claims, but how such claims were argued. For example, we noticed the author’s use of repetition in Genesis 1: time, command, execution, assessment, and time.[iv] Again, we employed our Bible commentaries and dictionaries to better understand the concepts that surround: image of God, chaos, dirt, etc.

In Front of the Text

We spent time asking a series of socio-economic questions posed by William Brown’s Exegetical Self-Profile: What is your family background ethnically, socially, and economically? How do your political views inform your biblical interpretation (or vice versa)? What do you consider to be the most pressing social or ethical issue today? Is Scripture relevant to it?”[v] Although we had set sail in the vast ocean, we now had a basic set of tools. We brought aspects to each of the worlds into conversation. A nationally known preacher had spoken against the role of women in the church. The group (decidedly more women than men) focused on how Genesis 1-2 may have presented the role of women to its intended audiences.

Moving Forward

There are a multitude of insights that this project has revealed: one is the way my congregation approaches the Scripture. While I do endorse a manner of reading/studying the Scripture, I am indebted to Peter Enns’ claim of the Scripture, “Rather than providing us with information to be downloaded, the Bible holds out for us an invitation to join an ancient well-traveled, and sacred quest to know God, the world we live in, and our place in it”.[vi] It is through the communal use of responsibly reading/studying the Scripture that we will gain the wisdom to hold a “fidelity to the text and novelty towards [it’s] audience”.[vii] There is no question that my seminary degree has helped me to enter into the Scripture in meaningful ways. However, the tools provided are most useful on the open sea of life, as we continue to listen for the Holy Spirit’s direction.

[i] Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its, Worth 4th ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014), 17.

[ii] Carolyn J. Sharp, Wrestling the Word: The Hebrew Scriptures and the Christian Believer (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2010), xv.

[iii] Richard N. Soulen and R. Kendall Soulen, Handbook of Biblical Criticism, 3rd ed.(Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 233-234.

[iv] Walter Brueggemann, Genesis. Interpretation (Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press, 1984), 30.

[v] William P. Brown, A Handbook To Old Testament Exegesis (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017), 12.

[vi] Peter Enns, How the Bible Actually Works*: In which I Explain How an Ancient, Ambiguous, and Diverse Book Leads Us to Wisdom Rather Than Answers—and Why That’s Great News (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2020), 10.

[vii] Phillips Brooks, Lectures on Preaching, Delivered before the Divinity School of Yale College in January and February 1877 (New York, NY: E. P. Dutton, 18770, 220-221.

Nick,

I appreciate your desire to help your people develop the interpretive tools that will allow them to grow as disciples. I think your focus on Genesis 1-2 is a great starting point for such an exercise. I hope that the dynamics of your Bible studies have changed from pastor led to a more collaborative model that listens to the way God still speaks to us through the Word. Blessings upon your ministry. I am thankful to have been on this path with you.

Grace and peace,

Eric Sanford