Introduction

Even in places where the soil is excellent and the land hasn’t been inundated by flooding or drought, cultivation remains necessary for preparing, tending, and bringing crops to harvest. One can go back and forth over till and no till, but the land must be nurtured if it is to sustain that which is sewn. Uncultivated land leads to death. This is also true of the lives of Christians. Formation as disciples of Christ and witnesses to the Gospel is a lifelong process culminating, hopefully, in a happy death bound for Glory. Such a process requires persistence, patience, and wisdom to see the process through to fruition. Old methods of catechetical education[i] may no longer be as effective just as farming techniques change with advances in agriscience.

St. Augustine Catholic Church has always been a parish cultivating the minds and hearts of young people through whole-person education. While this focus has not changed, demographics have changed. These changing demographics when examined in the light of current scholarship suggests that what we have always done—which is never a completely honest statement—can no longer continue. For far too long, catechetical education has been driven by a classroom model where one catechist is paired with one age group or grade level. It ends up looking like school with a religious twist. Furthermore, this outdated model tends to emphasize doctrine and morality while glossing over scripture, experience, and justice. This method also leaves families out of the equation, and it is the lack of family inclusion I found most disappointing.

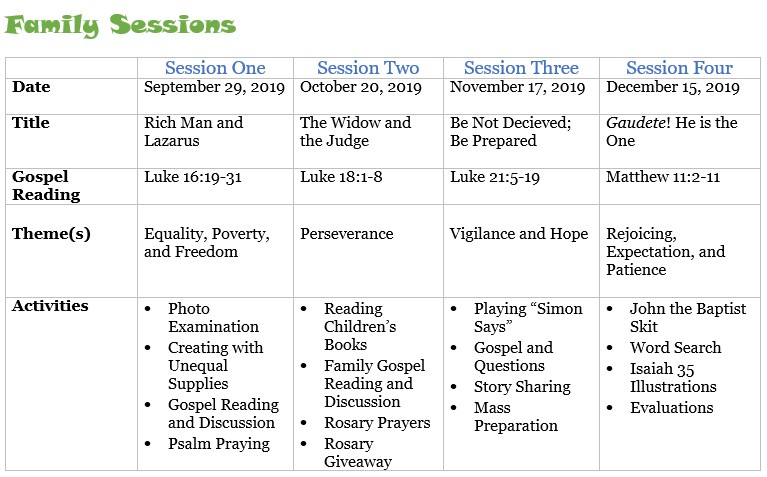

Family catechetical education is the way forward. We piloted a program beginning in Fall 2019. While keeping our traditional model, we held family sessions one Sunday per month September through December. From the outset, the families involved were informed that what we were doing was experimental while built on the belief that families should and do learn and grow together in faith. Knowing the program was experimental families were willing to engage the process. Each of the four sessions focused on the gospel reading for that Sunday, and themes were drawn from those reading around which activities and discussion were informed.

Family?

An early question that we had to deal with was how to define the term, ‘family.’ It was clear that a narrow definition would align with a more traditional approach, but it would also disregard the reality we faced with differing demographics. Brenda Snailum writes, “family is best understood as a complex interrelated system, and the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”[ii] Although religious educators and pastoral ministers may not readily think of families as systems, it allows for a degree of objectivity to help undergird the project overall. Families are relational and the interrelationships of individual members are more complicated than the Church at times admits. This makes the task of religious education, faith formation, and catechesis a process which must navigate the complexities, but which has often been left unattended. This means that the task of the Church and families in educating all members is also a complex reality.

As we looked at our participants, we found many models of family. Some were just children and their mothers; one was an adopted child who didn’t physically look anything like her parents. Another family was a grandmother, her daughter, and three boys. We also had a family with a mother and father and their one daughter and one son. Some families represented a mix of Christian denominations. The expansive definition above allows us to be rooted in reality.

What Kind of Education and Why?

Thomas H. Groome defines Christian religious education as “a political activity with pilgrims in time that deliberately and intentionally attends with them to the activity of God in our present, to the Story of the Christian faith community, and to the Vision of God’s Kingdom, the seeds of which are already among us.”[iii] Carefully, Groome distinguishes between religious education and catechesis, but notes that the methods of catechesis, generally oral instruction, are those most used to provide religious education. It is from this understanding of catechesis then, that the Catholic Church has developed programs for religious education. This understanding, however, can miss part of what is included in Groome’s definition.

It is the telling of the stories of Christian faith that has emerged, and the method for doing so has been to place students in a classroom with a teacher, that is a catechist, who then tells the story. The immediate issue that arises is the telling of the story comes from the perspective and the context of the catechist, and it does not always reflect contemporary scholarship. There are still people who are taught Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible. However, biblical scholars have shown there were multiple others with varied oral traditions in which the earliest books of Scripture were recorded. This illustrates one reason why a classroom dominated by one educator may not always be the best technique for handing on the faith.

Another issue is that hearing and retelling the story is only part of what Groome is getting at. The story has little meaning if it fails to impact the lives of hearers. Catechetical education is not simply learning the story, but also making the story one’s own. The story transforms as those who are learning perform the story. James K. A. Smith refers to this performance or practice as ‘tuning’. Christian education tunes hearers who make the story their own to then rehearse the story in their own bodies. “We are conscripted into a Story through those practices that enact and perform and embody a Story about the good life.”[iv] This begins in worship at Mass, but it must also become part of what happens in programs of catechetical education. Hearing and practicing the stories can lead to transformation, and if families are practicing together then the impact on Church and society is more powerful.

According to Groome, we inaugurate this transformation by recognizing and respecting the inherent dignity of all learners. All are learning together, and all are imprinted with the image of God. We should presume that when we acknowledge the spiritual nature of learners, then we delve into and teach souls, which means people’s truest selves are engaged.[v] This opens the way for authentic learning that can be coupled with practical application. The story of Christian faith, grounded in the Bible, is one that is both challenging and rewarding. Catechetical education must provide access to “the whole historical reality and spiritual wisdom of Christian revelation” with “the demands and promises that this faith makes upon the lives of its adherents and communities.”[vi] Authentic catechetical education allows learners to share their experiences, to hear the experience of others, to acknowledge the themes of failure and redemption in our history and to know they are part of the whole. In other words, learning takes place in the context of the community in which one is becoming. One’s self is transformed to be for others. Family catechetical education builds a community that provides a path to personal and communal transformation.

The table above gives a nice overview of the four sessions. Clearly the sessions were focused on the scriptures for that Sunday. We also devised activities that were relevant, hands-on, and could be completed with simple, direct instructions. Once the families had their instructions, I was able to serve as a facilitator. Simple directions also made it easy to translate for our families who primarily speak Spanish. We witnessed parents engaged with their children, and it was not always apparent who was teaching whom.

A highlight was that following the November 17 Family Session, children helped with ministries at Mass by greeting, reading, taking up the collection, and bearing gifts to the altar. It was a wonderful witness to the community, but also a witness to the families as they clearly experienced a connection to what we were doing in session and what was happening during worship. It was a moment of liturgical catechesis that happened without further instruction.

Findings

What I found in the process of piloting the family catechesis program is that if participants know from the beginning that what is being done is experimental and yet fundamental, they are receptive and willing to enter the process with some uncertainty. To take what is written in the Gospel or other readings for Sundays and create an experience wherein families are more in touch with their faith and are growing not only in knowledge but also in love, is an immense challenge. We adjusted along the way as we received feedback whether in body language, mood, or what was spoken to us.

The dynamics at St. Augustine are seemingly in flux. The number of Hispanic families is growing in this area of the United States, and the Church must be responsive to the unique needs, gifts, and heritage this brings. According to the broader definition used by the U.S. Catholic Bishops, the parish could be referred to as a ‘shared parish.’[vii] However, there aren’t distinct ministries or even a Mass in Spanish that would cause the parish to be defined more narrowly as Brett Hoover does in his ethnographic study. Hoover defines the shared parish as “parishes with two or more cultural groups, each with distinct masses and ministries, but who share the same parish facilities.”[viii] Unfortunately, at St. Augustine few people are even talking about creating unique experiences or pastoral outreach to Hispanic families.[ix] There is an overarching ‘habitus’ within the parish that keeps most people doing what they do without much reflection or thought about trying something new.[x]

Not only are the directions given or the questions asked important, but the activities need to have a broad appeal that engage families in a variety of ways. These four sessions used both images and words, but also invited creativity with posters, pictures, and coloring. The two activities that were most appreciated were reading story books together and creating a poster to illustrate the passage from the book of Isaiah. Both activities got families talking, sharing, being creative, and caused them to think about their own lives of faith with little prompting. The activities brought families together for a common purpose and they learned something about the faith we profess through the process.

One regret is that we did not do a good job of just letting families get to know one another. The focus early on was on the project itself and not as much on the people involved in the project. That was noted by more than one parent at the fourth session. Some of the families know one another, but others do not, and that has caused a disconnect in what we are trying to accomplish. It is clear to me now that sustaining the family sessions will require families who support one another, but it is tough to support those we do not know.

St. Augustine Church, Rensselaer, Indiana

Conclusion

Our family sessions gave space for people to grow in their expression of faith. Whereas in a classroom the loudest voice is heard or the most talkative are recognized, family catechetical education used the language of ‘we’ and ‘us’ over ‘I’ and ‘me’ because families shared from a collective and not an individual perspective. This emergence of a collective voice was the best surprise for me, and possibly the best outcome of this experimentation. People let go of self, at least for those four hours, to allow something new to be born. How beautiful the voices that lift up one another! I am convinced family catechetical education, through ongoing experimentation, will continue at St. Augustine.

Just as each spring new crops are planted and each autumn crops are harvested, catechetical education has its own seasons. Its shape will likely evolve as all grow, mature, and respond to needs that arise. I know I will not see the full impact of this undertaking, but I remain hopeful it will make a difference. The seeds have been planted and we are nurturing their growth through this process. The prayers are still being offered, the questions are still being asked, and people are being formed to lead lives that give witness to the gospel. I hope the people of St. Augustine will continue to share faith, build community, and cultivate domestic churches.

[i] I prefer to use the term catechetical education, which is suggested by Thomas H. Groome, as it more closely reflects what we are doing as a parish. Other terms in use are catechesis, religious education, and faith formation. See Thomas H. Groome, “Total Catechesis/Religious Education: A Vision for Now and Always,” in Horizons & Hopes: The Future of Religious Education, ed. Thomas H. Groome and Harold Daly Horell (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2003).

[ii] Brenda A. Snailum, “How Families Shape the Faith of Younger Generations,” in Teaching the Next Generations: A Comprehensive Guide for Teaching Christian Formation, ed. Terrence D. Linhart (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016), 177.

[iii] Thomas H. Groome, Christian Religious Education: Sharing Our Story and Vision (San Francisco: Harper and Row Publishers, 1980), 25. The definition is italicized in the book.

[iv] James K. A. Smith, Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works, vol. 2, Cultural Liturgies (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013), 137.

[v] Thomas H. Groome, Will There Be Faith? A New Vision for Educating and Growing Disciples (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 67.

[vi] Groome, Will There Be Faith, 68.

[vii] “USCCB Launches Multicultural Parish Resource, Best Practices for ‘Shared Parishes,’” accessed February 14, 2020, http://www.usccb.org/news/2014/14-051.cfm.

[viii] Brett C. Hoover, The Shared Parish: Latinos, Anglos, and the Future of the U.S. Catholicsim (New York: New York Universisty Press, 2014), 2.

[ix] Hosffman Ospino, “Ten Reality Checks About Young Hispanics in Catholic Schools and Colleges,” in Our Catholic Children: Ministry with Hispanic Youth and Young Adults, ed. Hosffman Ospino (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 2018). Ospino shares his observations regarding biases and the need for pastoral outreach to engage and involve Hispanic families and youth. What he notes is endemic in the U.S. and specifically in the Catholic Church, and a parish like St. Augustine is not unique in this regard.

[x] Mary Clark Moschella, Ethnography as a Pastoral Practice: An Introduction (Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim Press, 2008), 52-55.